Glucose Transport in Human Placenta and the Effect of GDM on Placental Glucose Transport

-

摘要: 胎盘是将母体葡萄糖转运至子体的重要器官,正常的胎盘结构和功能为胎儿从母体有效摄取葡萄糖提供保障。胎盘上葡萄糖转运主要依赖于胎盘上的葡萄糖转运体(glucose transporters,GLUTs)。此外,胎盘自身对葡萄糖代谢也会影响经胎盘的葡萄糖转运。妊娠期糖尿病(gestational diabetes mellitus,GDM)是一种常见的妊娠期并发症。GDM患者胎盘上葡萄糖转体运功能的异常,可能是造成其子代产生不良结局的原因之一。就正常胎盘上的葡萄糖转运进行论述,并且探讨GDM患者胎盘上葡萄糖转运的改变及可能的分子机制。Abstract: Placenta plays an important role in the process of glucose transfer from maternal to fetus. The normal structure and function of the placenta guarantee the fetus to take up glucose effectively from maternal side over the gestation. Glucose transplacental transfer mainly depends on the glucose transporters (GLUTs). And the placenta and other factors such as placental glucose metabolic activity could also affect the glucose transplacental transfer. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a main complication of pregnancy. Fetal adverse outcomes from GDM patients may be caused by the abnormality of glucose transport in the placenta. This review aims to discuss the glucose transplacental transfer on the normal placenta and summarize some changes and molecular mechanism that have been reported about glucose transplacental transfer in the GDM.

-

Key words:

- Placenta /

- Glucose transport /

- Glucose transporters /

- GDM

-

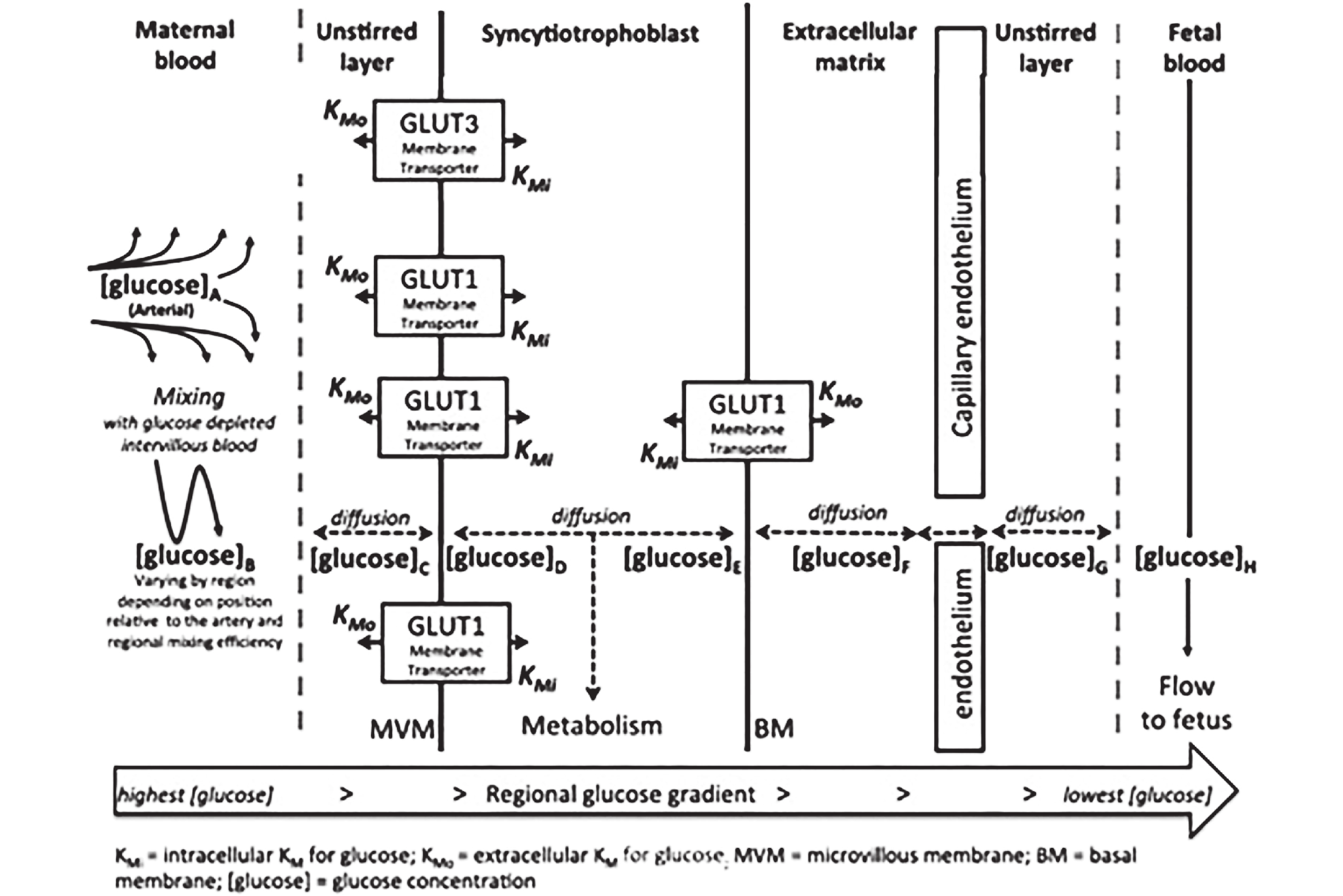

图 1 胎盘上的葡萄糖转运简图[1]

注:Kmi :葡萄糖的胞间转运米氏常数;Kmo :葡萄糖的胞外转运米氏常数; [glucose] :葡萄糖浓度。葡萄糖通过GLUTs从血糖浓度较高的母体侧扩散到血糖浓度较低的胎儿侧。母体侧血糖浓度从动脉到静脉依次是[glucose] A > [glucose ]B > [glucose] C > > [glucose] H,胎盘各个区域的葡萄糖浓度由母体侧转运进来的血糖和各个区域向胎儿侧扩散的葡萄糖共同决定。

Figure 1. Transplacental glucose transport

-

[1] Day P E,Cleal J K,Lofthouse E M,et al. What factors determine placental glucose transfer kinetics?[J]. Placenta,2013,34(10):953-958. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.07.001 [2] Stanirowski P J,Szukiewicz D,Pyzlak M,et al. Impact of pre-gestational and gestational diabetes mellitus on the expression of glucose transporters GLUT-1,GLUT-4 and GLUT-9 in human term placenta[J]. Endocrine,2017,55(3):799-808. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1202-4 [3] Illsley N P,Baumann M U. Human placental glucose transport in fetoplacental growth and metabolism[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis,2020,1866(2):165-359. [4] Jansson T,Wennergren M,Illsley N P. Glucose transporter protein expression in human placenta throughout gestation and in intrauterine growth retardation[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab,1993,77(6):1554-1562. [5] Illsley N P. Placental glucose transport in diabetic pregnancy[J]. Clin Obstet Gynecol,2000,43(1):116-126. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200003000-00012 [6] Vardhana P A,Illsley N P. Transepithelial glucose transport and metabolism in BeWo choriocarcinoma cells[J]. Placenta,2002,23(8-9):653-660. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0857 [7] Brown K,Heller D S,Zamudio S,et al. Glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) protein expression in human placenta across gestation[J]. Placenta,2011,32(12):1041-1049. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.09.014 [8] Janzen C,Lei M Y,Cho J,et al. Placental glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) is up-regulated in human pregnancies complicated by late-onset intrauterine growth restriction[J]. Placenta,2013,34(11):1072-1078. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.08.010 [9] James-Allan L B,Arbet J,Teal S B,et al. Insulin stimulates GLUT4 trafficking to the syncytiotrophoblast basal plasma membrane in the human placenta[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab,2019,104(9):4225-4238. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02778 [10] Ericsson A,Hamark B,Powell T L,et al. Glucose transporter isoform 4 is expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast of first trimester human placenta[J]. Hum Reprod,2005,20(2):521-530. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh596 [11] Hiden U,Glitzner E,Hartmann M,et al. Insulin and the IGF system in the human placenta of normal and diabetic pregnancies[J]. J Anat,2009,215(1):60-68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01035.x [12] Desoye G,Hartmann M,Blaschitz A,et al. Insulin receptors in syncytiotrophoblast and fetal endothelium of human placenta. Immunohistochemical evidence for developmental changes in distribution pattern[J]. Histochemistry,1994,101(4):277-285. doi: 10.1007/BF00315915 [13] Augustin R,Carayannopoulos M O,Dowd L O,et al. Identification and characterization of human glucose transporter-like protein-9 (GLUT9):Alternative splicing alters trafficking[J]. J Biol Chem,2004,279(16):16229-16236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312226200 [14] Gude N M,Stevenson J L,Rogers S,et al. GLUT12 expression in human placenta in first trimester and term[J]. Placenta,2003,24(5):566-570. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0925 [15] Michelsen T M,Holme A M,Holm M B,et al. Uteroplacental glucose uptake and fetal glucose consumption:A quantitative study in human pregnancies[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab,2019,104(3):873-882. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01154 [16] Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks D A, et al. The international federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: A pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care [J]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2015, 131(Suppl 3 ): S173-211. [17] Wei Y,Yang H,Zhu W,et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study group criteria is suitable for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis:Further evidence from China[J]. Chin Med J (Engl),2014,127(20):3553-3556. [18] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 180:Gestational diabetes mellitus[J]. Obstet Gynecol,2017,130(1):e17-e37. [19] Dugas C,Perron J,Kearney M,et al. Postnatal prevention of childhood obesity in offspring prenatally exposed to gestational diabetes mellitus:Where are we now?[J]. Obes Facts,2017,10(4):396-406. doi: 10.1159/000477407 [20] Ashfaq M,Janjua M Z,Channa M A. Effect of gestational diabetes and maternal hypertension on gross morphology of placenta[J]. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad,2005,17(1):44-47. [21] Desoye G,Cervar-Zivkovic M. Diabetes mellitus,obesity,and the placenta[J]. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am,2020,47(1):65-79. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.11.001 [22] Madazli R,Tuten A,Calay Z,et al. The incidence of placental abnormalities,maternal and cord plasma malondialdehyde and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and nondiabetic controls[J]. Gynecol Obstet Invest,2008,65(4):227-232. doi: 10.1159/000113045 [23] Hahn T,Barth S,Weiss U,et al. Sustained hyperglycemia in vitro down-regulates the GLUT1 glucose transport system of cultured human term placental trophoblast:A mechanism to protect fetal development?[J]. Faseb J,1998,12(12):1221-1231. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.12.1221 [24] Illsley N P,Sellers M C,Wright R L. Glycaemic regulation of glucose transporter expression and activity in the human placenta[J]. Placenta,1998,19(7):517-524. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(98)91045-1 [25] Basak S,Vilasagaram S,Naidu K,et al. Insulin-dependent,glucose transporter 1 mediated glucose uptake and tube formation in the human placental first trimester trophoblast cells[J]. Mol Cell Biochem,2019,451(1-2):91-106. doi: 10.1007/s11010-018-3396-7 [26] Jansson T,Ekstrand Y,Wennergren M,et al. Placental glucose transport in gestational diabetes mellitus[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol,2001,184(2):111-116. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.108075 [27] Gaither K,Quraishi A N,Illsley N P. Diabetes alters the expression and activity of the human placental GLUT1 glucose transporter[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab,1999,84(2):695-701. [28] Yao G,Zhang Y,Wang D,et al. GDM-induced macrosomia is reversed by Cav-1 via AMPK-mediated fatty acid transport and GLUT1-mediated glucose transport in placenta[J]. PLoS One,2017,12(1):1-18. [29] Stanirowski P J,Lipa M,Bomba-Opoń D,et al. Expression of placental glucose transporter proteins in pregnancies complicated by fetal growth disorders[J]. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol,2021(123):95-131. [30] Joshi N P,Mane A R,Sahay A S,et al. Role of placental glucose transporters in determining fetal growth[J]. Reprod Sci,2021,23(5):114-119. [31] Sciullo E,Cardellini G,Baroni M,et al. Glucose transporters (GLUT 1,GLUT 3) mRNA in human placenta of diabetic and non-diabetic pregnancies[J]. Ann Ist Super Sanita,1997,33(3):361-365. [32] Kainulainen H,Järvinen T,Heinonen P K. Placental glucose transporters in fetal intrauterine growth retardation and macrosomia[J]. Gynecol Obstet Invest,1997,44(2):89-92. doi: 10.1159/000291493 [33] Valent A M,Choi H,Kolahi K S,et al. Hyperglycemia and gestational diabetes suppress placental glycolysis and mitochondrial function and alter lipid processing[J]. Faseb J,2021,35(3):e21423. [34] Carey E A,Albers R E,Doliboa S R,et al. AMPK knockdown in placental trophoblast cells results in altered morphology and function[J]. Stem Cells Dev,2014,23(23):2921-2930. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0092 [35] Martino J,Sebert S,Segura M T,et al. Maternal body weight and gestational diabetes differentially influence placental and pregnancy outcomes[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab,2016,101(1):59-68. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2590 [36] 凌晓娟,黄震,李红霞. 孕妇体重和妊娠期糖尿病对胎盘和妊娠结局的影响[J]. 中国实验诊断学,2019,23(7):1109-1116. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-4287.2019.07.001 [37] Shang M,Wen Z. Increased placental IGF-1/mTOR activity in macrosomia born to women with gestational diabetes[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract,2018,146(8):211-219. [38] Jansson T,Aye I L,Goberdhan D C. The emerging role of mTORC1 signaling in placental nutrient-sensing[J]. Placenta,2012,33(11):e23-29. [39] Roos S,Lagerlöf O,Wennergren M,et al. Regulation of amino acid transporters by glucose and growth factors in cultured primary human trophoblast cells is mediated by mTOR signaling[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol,2009,297(3):723-731. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00191.2009 [40] Dennis P B,Jaeschke A,Saitoh M,et al. Mammalian TOR:A homeostatic ATP sensor[J]. Science,2001,294(5544):1102-1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518 [41] Xu J,Lu C,Wang J,et al. Regulation of human trophoblast GLUT3 glucose transporter by mammalian target of rapamycin signaling[J]. Int J Mol Sci,2015,16(6):13815-13828. [42] Muralimanoharan S,Maloyan A,Myatt L. Mitochondrial function and glucose metabolism in the placenta with gestational diabetes mellitus:Role of miR-143[J]. Clin Sci (Lond),2016,130(11):931-941. doi: 10.1042/CS20160076 [43] Baumann M U,Schneider H,Malek A,et al. Regulation of human trophoblast GLUT1 glucose transporter by insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)[J]. PLoS One,2014,9(8):1-28. -

下载:

下载: