Development of A Plasma Osmolality Prediction Model for the Risk of In-hospital Death in Critically Ill Patients with Acute ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

-

摘要:

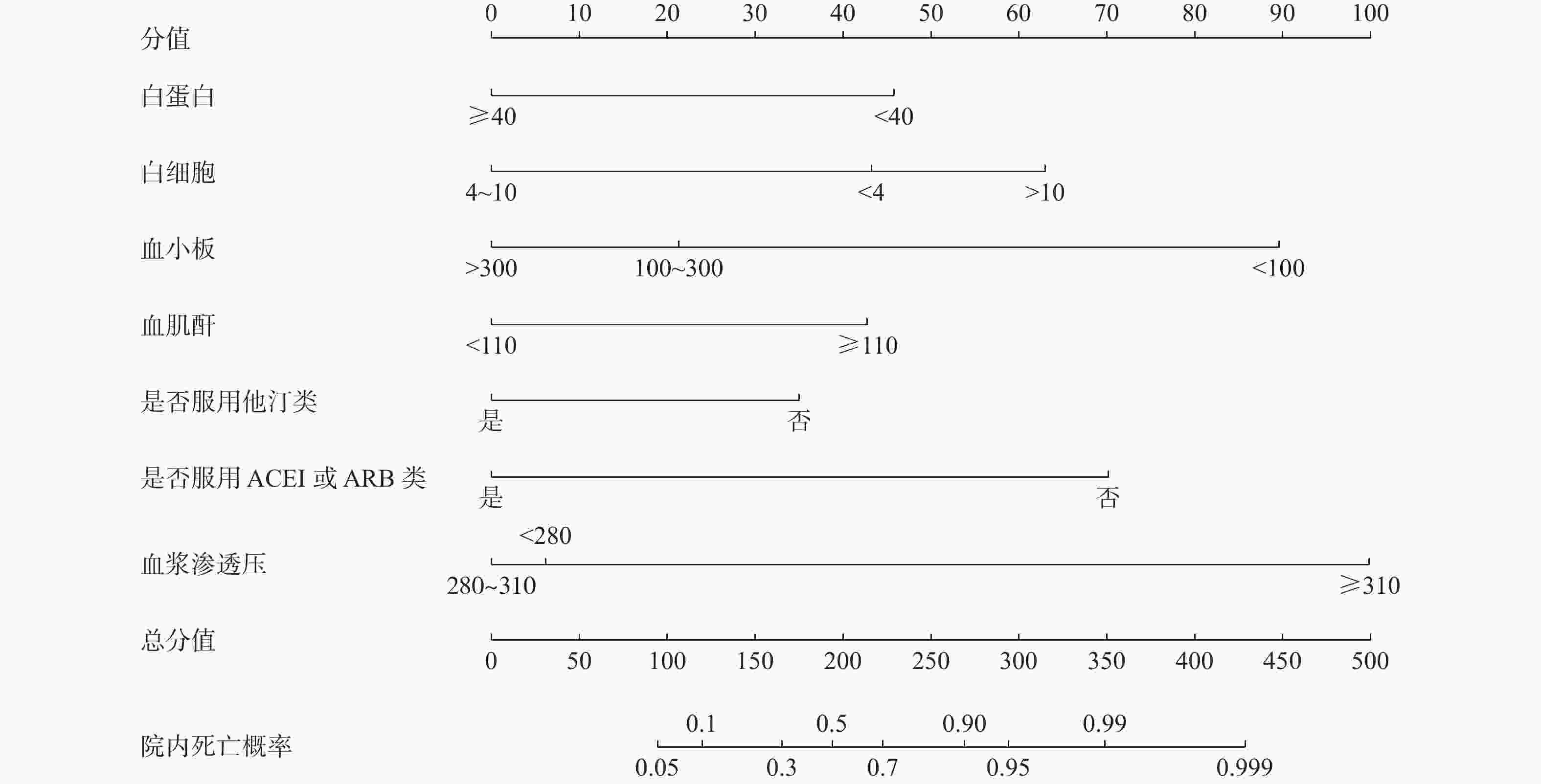

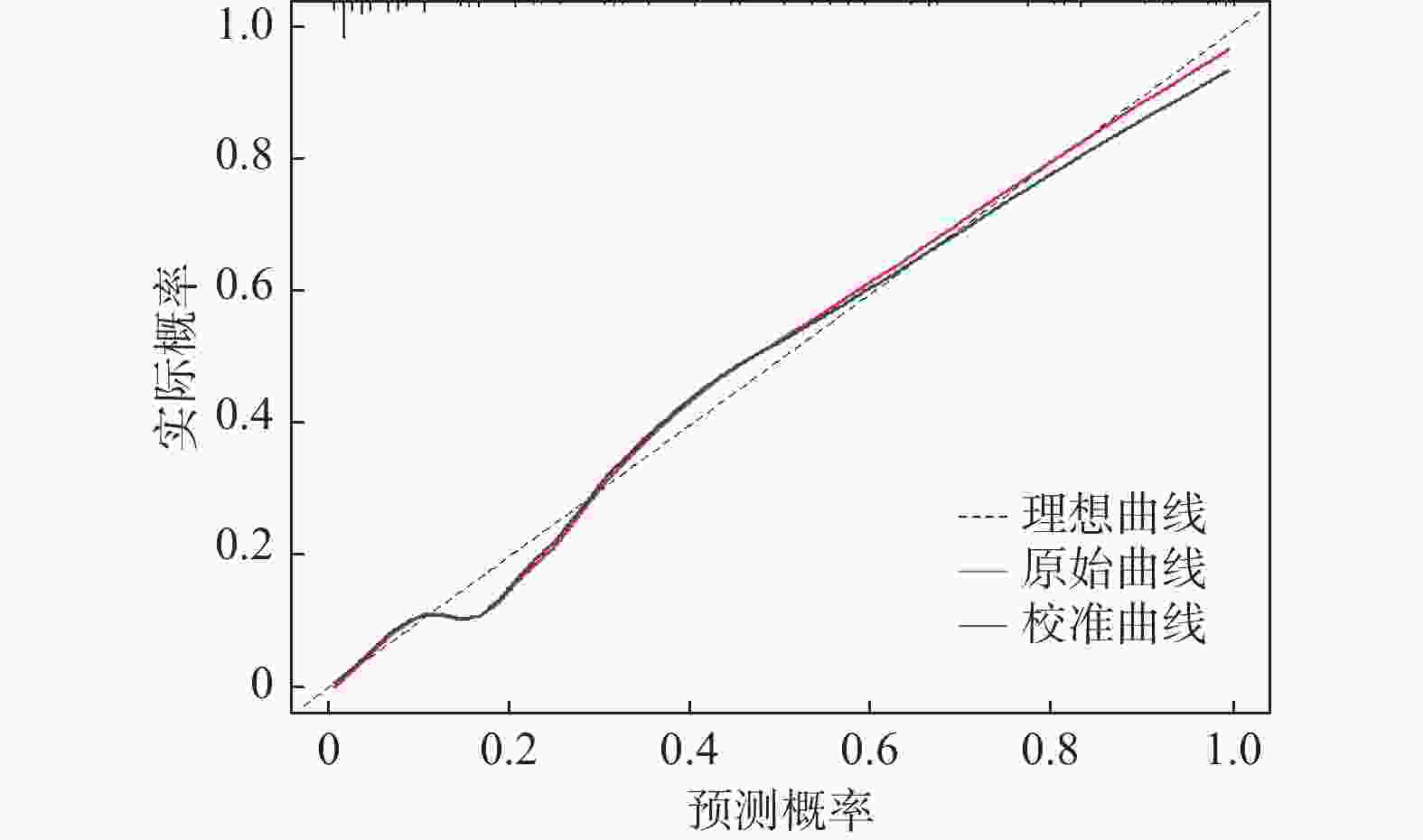

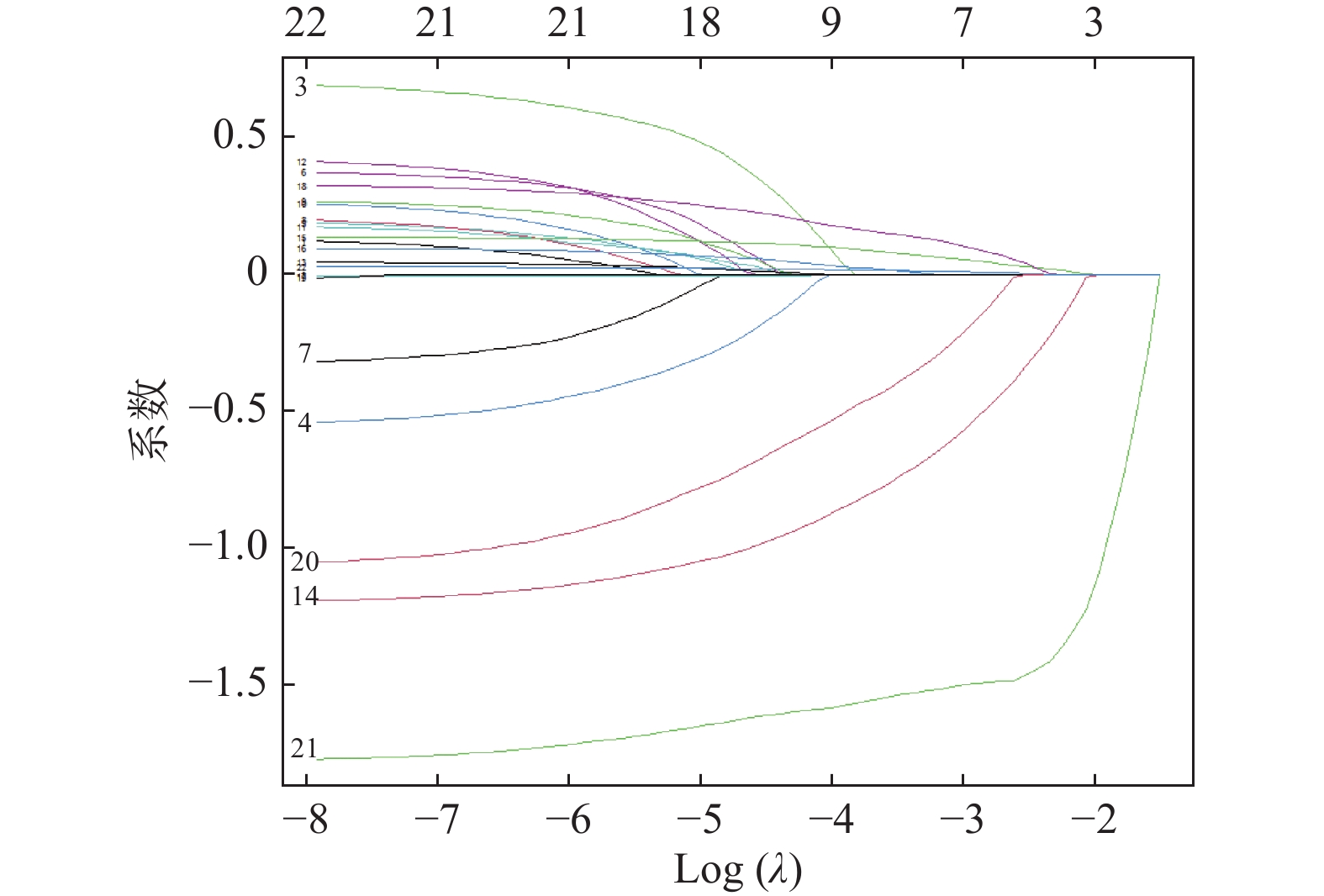

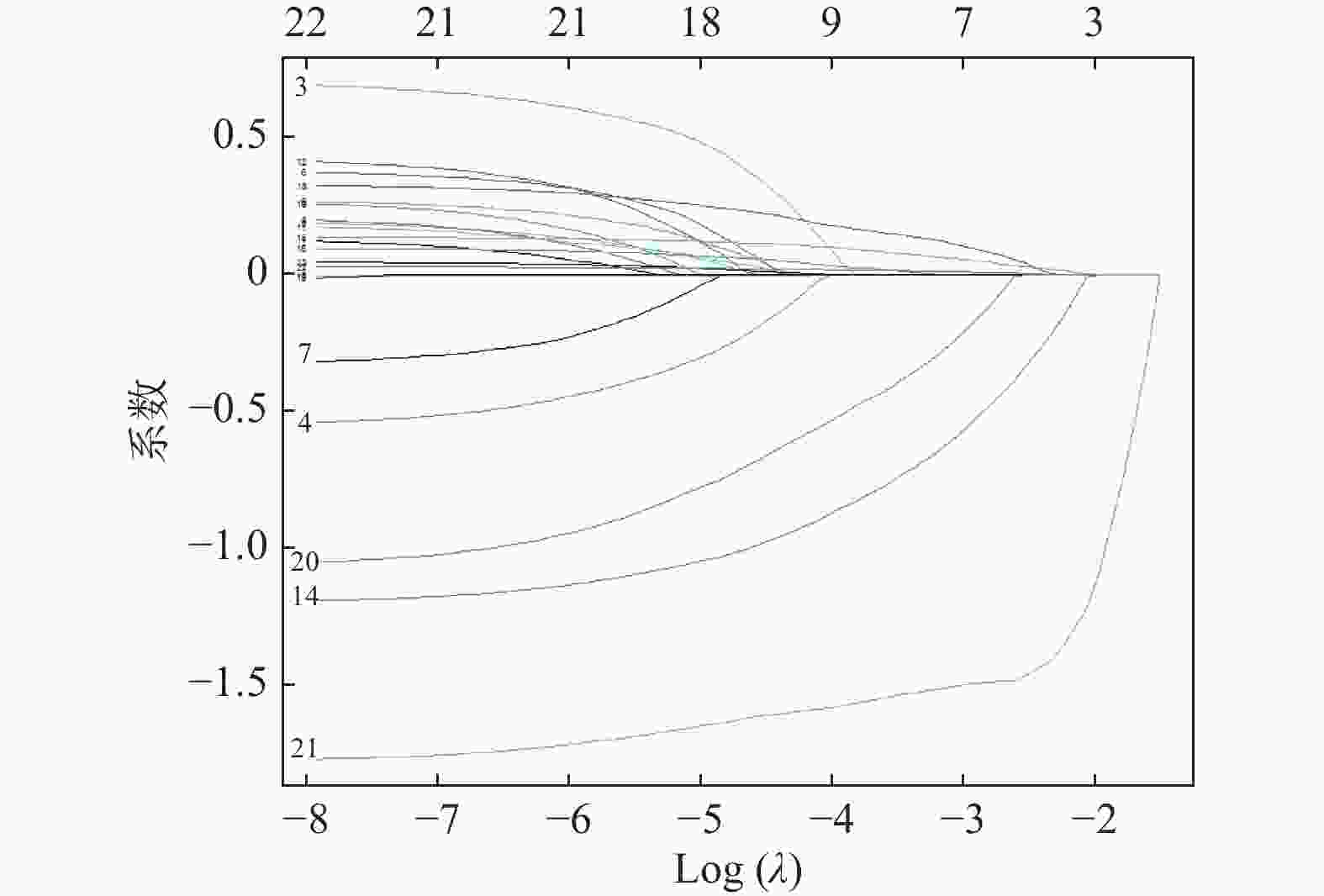

目的 建立并验证血浆渗透压对急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死(acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction,STEMI)重症患者院内死亡风险预测模型。 方法 通过回顾性分析患者电子病历资料,选取2015年1月至2020年12月于云南大学附属医院心血管内科住院的STEMI重症患者,提取患者的一般信息、实验室检查、合并疾病及用药情况等,筛选STEMI重症患者院内死亡风险危险因素并建立预测模型。 结果 利用LASSO回归及多因素Logistic回归筛选出白蛋白(ALB)、白细胞(WBC)、血小板(PLT)、血肌酐(Scr)、是否服用他汀类药物、是否服用血管紧张素转化酶抑制剂(ACEI)或血管紧张素转化酶受体拮抗剂(ARB)类药物、血浆渗透压为STEMI重症患者是否发生院内死亡的独立预测因子(P < 0.05),据此7个预测变量绘制列线图,模型检验结果显示其区分度、校准度较好,决策曲线分析(DCA)显示阈值概率5%~95%时,临床使用该模型是可以获益的。 结论 构建的包含7个变量预测模型具有较好的区分度和校准度,可作为评估STEMI重症患者院内死亡风险参考工具。 -

关键词:

- 急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死 /

- 院内死亡 /

- 预测模型 /

- 列线图

Abstract:Objective To develop and validate a plasma osmolality prediction model for the risk of in-hospital death in critically ill patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Methods By retrospective analysis of patients' electronic medical record data, patients with severe STEMI admitted to the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University from January 2015 to December 2020 were selected. General information, laboratory examination, comorbid diseases and medications of the patients were extracted to screen the risk factors of in-hospital death of severe STEMI patients and establish a prediction model. Results LASSO regression and multivariate Logistic regression were used and identified albumin (ALB), leukocyte (WBC), platelet (PLT), serum creatinine (Scr), statins medication, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) medication or angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor antagonists (ARB), and plasma osmosis Pressure as independent predictor of in-hospital death in severe STEMI patients (P < 0.05). A nomogram was drawn based on the 7 predictive variables. Model test results showed good differentiation and calibration, and decision curve analysis (DCA) showed a threshold probability of 5%-95%. Conclusion The prediction model has good discrimination and calibration, and can be used as a reference tool for assessing the risk of in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with STEMI. -

表 1 患者一般资料比较[($\bar x \pm s $),n(%),M(P25,P75)]

Table 1. Comparison of general information of patients [($\bar x \pm s $),n(%),M(P25,P75)]

临床特征 未发生院内死亡(n=632) 院内死亡(n = 177) W/t/χ2 P 男性 402(63.6) 107(60.5) 0.463 0.496 年龄(岁) 68.0 ± 13.7 71.8 ± 13.6 −3.294 < 0.001* 吸烟史 113(17.9) 63(35.6) 0.183 0.669 高血压 359(56.8) 90(50.8) 1.753 0.186 糖尿病 231(36.6) 64(36.2) 0.000 0.993 Killip≥2级 322(50.9) 102(57.6) 2.212 0.137 COPD(%) 17(2.7) 10(5.6) 2.894 0.089 慢性肾脏病 132(20.9) 52(29.4) 5.203 0.022* 高脂血症 324(51.3) 69(39.0) 7.867 0.005* 瓣膜病 133(21.0) 44(24.9) 0.965 0.326 心房颤动 201(31.8) 76(42.9) 7.127 0.008* 脑梗死 37(5.9) 15(8.5) 1.173 0.279 服用阿司匹林 618(97.8) 155(87.6) 31.569 < 0.001* 服用他汀类 600(94.9) 128(72.3) 76.037 < 0.001* 服用ACEI/ARB 584(92.4) 73(41.2) 233.870 < 0.001* WBC(×109/L) 8.9(7.0,10.9) 14.0(9.5,17.5) 28211 < 0.001* PLT(×109/L) 246(192,338) 172(100,279) 75920 < 0.001* RDW(%) 14.4(13.5,15.8) 15.9(14.6,17.7) 34000 < 0.001* ALB(g/L) 35(30,39) 28(24,32) 84690 < 0.001* Scr(μmol/L) 88.4(70.7,114.9) 167.9(97.2,265.2) 31276 < 0.001* cTnT(ng/mL) 0.62(0.05,2.58) 0.92(0.16,4.11) 46775 < 0.001* 血浆渗透压(mOsm/L) 294.5(289.7,298.0) 297.4(288.9,307.3) 36175 < 0.001* COPD = 慢性阻塞性肺疾病。*P < 0.05。 表 2 训练集和验证集的一般资料比较[($\bar x \pm s $),n(%),M(P25,P75)]

Table 2. Comparison of data in training and validation groups [($\bar x \pm s $),n(%),M(P25,P75)]

临床特征 训练集(n = 573) 验证集(n = 236) W/t/χ2 P 男性 357(62.3) 152(64.4) 0.793 0.629 年龄(岁) 68.9 ± 13.6 68.7 ± 14.2 0.237 0.939 有吸烟史 123(21.5) 53(22.5) 0.217 0.511 高血压 311(54.3) 138(58.5) 0.018 0.310 糖尿病 213(37.2) 82(34.7) 0.695 0.577 Killip≥2级 302(52.7) 122(51.7) 0.337 0.854 COPD 17(3.0) 10(4.2) 0.871 0.484 慢性肾脏病 131(22.9) 53(22.5) 0.021 0.974 高脂血症 275(48.0) 118(50.0) 1.271 0.659 瓣膜病 126(22.0) 51(21.6) 0.048 0.980 心房颤动 199(34.7) 78(33.1) 0.093 0.707 脑梗死 35(6.1) 17(7.2) 0.174 0.674 服用阿司匹林 545(95.1) 228(96.6) 0.227 0.452 服用他汀类 511(89.2) 217(91.9) 0.027 0.287 服用ACEI/ARB 461(80.5) 196(83.1) 2.024 0.447 WBC(×109/L) 9.5(7.5,11.9) 9.1(7.0,11.9) 64445 0.114 PLT(×109/L) 237(172,328) 242(176,329) 64776 0.592 RDW(%) 14.7(13.6,16.3) 14.7(13.7,16.2) 65879 0.959 ALB(g/L) 33(28,38) 34(28,38) 72021 0.881 Scr(μmol/L) 88.4(70.7,132.6) 97.2(70.7,150.3) 66992 0.439 cTnT(ng/mL) 0.81(0.07,3.05) 0.57(0.08,1.99) 68391 0.128 血浆渗透压(mOsm/L) 294.5(289.7,298.9) 294.6(289.4,300.2) 66566 0.691 注:COPD = 慢性阻塞性肺疾病。 表 3 LASSO回归筛选的8个变量的多因素Logistic回归结果

Table 3. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis of 8 variables

变量 OR 95%CI P WBC(×109/L)

4.0~10(参照)

1.0

-

-< 4.0 3.607 0.890~14.693 0.072 > 10.0 6.851 4.001~12.133 < 0.001* ALB(g/L)

≥40(参照)

1.0

-

-< 40 2.602 1.570~4.335 < 0.001* PLT(×109/L)

100~300(参照)

1.0

-

-< 100 5.625 2.493~13.249 < 0.001* > 300 0.475 0.267~0.827 0.009* Scr(μmol/L)

< 110(参照)

1.0

-

-> 110 3.231 1.928~5.466 < 0.001* RDW(%)

13~14(参照)

1.0

-

-< 13.0 0.477 0.068~1.998 0.370 > 14.0 1.563 0.831~3.025 0.174 血浆渗透压(mOsm/L)

280~310(参照)

1.0

-

-< 280 1.255 0.724~2.177 0.417 > 310 15.765 4.706~73.703 < 0.001* 服用他汀类药物 0.350 0.174~0.701 0.003* 服用ACEI或ARB 0.144 0.084~0.244 < 0.001* *P < 0.05。 -

[1] Liu S,Li Y,Zeng X,et al. Burden of cardiovascular diseases in China,1990-2016:Findings from the 2016 global burden of disease study[J]. JAMA Cardiol,2019,4(4):342-352. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0295 [2] Fan F,Li Y,Zhang Y,et al. Chest pain center accreditation is associated with improved in-hospital outcomes of acute myocardial infarction patients in China:Findings from the CCC-ACS project[J]. J Am Heart Assoc,2019,8(21):e013384. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013384 [3] Garcia-Osuna A,Sans-Rosello J,Ferrero-Gregori A,et al. Risk assessment after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:Can biomarkers improve the performance of clinical variables[J]. J Clin Med,2022,11(5):1266. [4] Roohafza H, Noohi F, Hosseini S G, et al. A cardiovascular risk assessment model according to behavioral, psychosocial and traditional factors in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (cras-mi): Review of literature and methodology of a multi-center cohort study[J]. Curr Probl Cardiol, 2022, 101158. [5] Kahraman S,Agus H Z,Avci Y,et al. The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (nlr) is associated with residual syntax score in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction[J]. Angiology,2021,72(2):166-173. doi: 10.1177/0003319720958556 [6] Lim E,Cheng Y,Reuschel C,et al. Risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality models for congestive heart failure and acute myocardial infarction:Value of clinical laboratory data and race/ethnicity[J]. Health Serv Res,2015,50(Suppl 1):1351-1371. [7] Wang X,Wang Z,Li B,et al. Prognosis evaluation of universal acute coronary syndrome:The interplay between syntax score and apob/apoa1[J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord,2020,20(1):293. doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01562-6 [8] Fukutomi M, Nishihira K, Honda S, et al. Difference in the in-hospital prognosis between ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with high killip class: Data from the Japan acute myocardial infarction registry[J]. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, 2020, 2048872620926681. [9] Rohla M,Freynhofer M K,Tentzeris I,et al. Plasma osmolality predicts clinical outcome in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention[J]. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care,2014,3(1):84-92. doi: 10.1177/2048872613516018 [10] Shen Y,Cheng X,Ying M,et al. Association between serum osmolarity and mortality in patients who are critically ill:A retrospective cohort study[J]. BMJ Open,2017,7(5):e015729. [11] Thygesen K,Alpert J S,Jaffe A S,et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018)[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,2018,72(18):2231-2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038 [12] Dorwart W V,Chalmers L. Comparison of methods for calculating serum osmolality form chemical concentrations,and the prognostic value of such calculations[J]. Clin Chem,1975,21(2):190-194. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/21.2.190 [13] Kosmidou I,Redfors B,Selker H P,et al. Infarct size,left ventricular function,and prognosis in women compared to men after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:Results from an individual patient-level pooled analysis of 10 randomized trials[J]. Eur Heart J,2017,38(21):1656-1663. [14] Reinstadler S J,Stiermaier T,Eitel C,et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation during ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction on infarct characteristics and prognosis[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging,2018,11(2):e006955. [15] Goriki Y,Tanaka A,Nishihira K,et al. A novel predictive model for in-hospital mortality based on a combination of multiple blood variables in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction[J]. J Clin Med,2020,9(3):852. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030852 [16] Liu Z,Liu L,Cheng J,et al. Risk prediction model based on biomarkers of remodeling in patients with acute anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction[J]. Med Sci Monit,2021,27(74):e927404. [17] Puodzhiukinene M Z,Mitskiavichene A A,Bluzhaĭte I. electrolyte concentration in the plasma and tissue cells of patients with ventricular arrhythmias in the acute period of myocardial infarction[J]. Kardiologiia,1987,27(2):98-100. [18] Urrows S T. Fluid and electrolyte balance in the patient with a myocardial infarction[J]. Nurs Clin North Am,1980,15(3):603-615. doi: 10.1016/S0029-6465(22)00573-4 [19] D A, Pandit V R, Kadhiravan T, et al, Cardiac arrhythmias, electrolyte abnormalities and serum cardiac glycoside concentrations in yellow oleander (cascabela thevetia) poisoning - a prospective study[J]. Clin Toxicol (Phila), 2019, 57(2): 104-111. [20] Epstein M,Roy-Chaudhury P. Arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in hemodialysis patients. Temporal profile,electrolyte abnormalities,and potential targeted therapies[J]. Nephrol News Issues,2016,30(4):23-26. [21] Capes S E,Hunt D,Malmberg K,et al. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes:A systematic overview[J]. Lancet,2000,355(9206):773-778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08415-9 [22] Laichuthai N,Abdul-Ghani M,Kosiborod M,et al. Newly discovered abnormal glucose tolerance in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular outcomes:A meta-analysis[J]. Diabetes Care,2020,43(8):1958-1966. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0059 [23] Lee J H,Bae M H,Yang D H,et al. Prognostic value of the age,creatinine,and ejection fraction score for 1-year mortality in 30-day survivors who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention after acute myocardial infarction[J]. Am J Cardiol,2015,115(9):1167-1173. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.02.001 [24] Acet H,Ertaş F,Bilik M Z,et al. The relationship between neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio,platelet to lymphocyte ratio and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction risk score in patients with ST elevation acute myocardial infarction before primary coronary intervention[J]. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej,2015,11(2):126-135. [25] Islam M S,Islam M N,Kundu S K,et al. Serum albumin level and in-hospital outcome of patients with first attack acute myocardial infarction[J]. Mymensingh Med J,2019,28(4):744-751. [26] Liu H,Zhang J,Yu J,et al. Prognostic value of serum albumin-to-creatinine ratio in patients with acute myocardial infarction:Results from the retrospective evaluation of acute chest pain study[J]. Medicine (Baltimore),2020,99(35):e22049. [27] Palatini P. Glomerular hyperfiltration:A marker of early renal damage in pre-diabetes and pre-hypertension[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant,2012,27(5):1708-1714. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs037 [28] Shiyovich A,Gilutz H,Plakht Y. White blood cell subtypes are associated with a greater long-term risk of death after acute myocardial infarction[J]. Tex Heart Inst J,2017,44(3):176-188. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-16-5768 [29] Han Y,Gong Z,Sun G,et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in patients with acute myocardial infarction[J]. Front Microbiol,2021,12:680101. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.680101 [30] Vavalle J P,van Diepen S,Clare R M,et al. Renal failure in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention:Predictors,clinical and angiographic features,and outcomes[J]. Am Heart J,2016,173:57-66. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.12.001 -

下载:

下载: