Application of High-flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in High-altitude Hypoxemia

-

摘要:

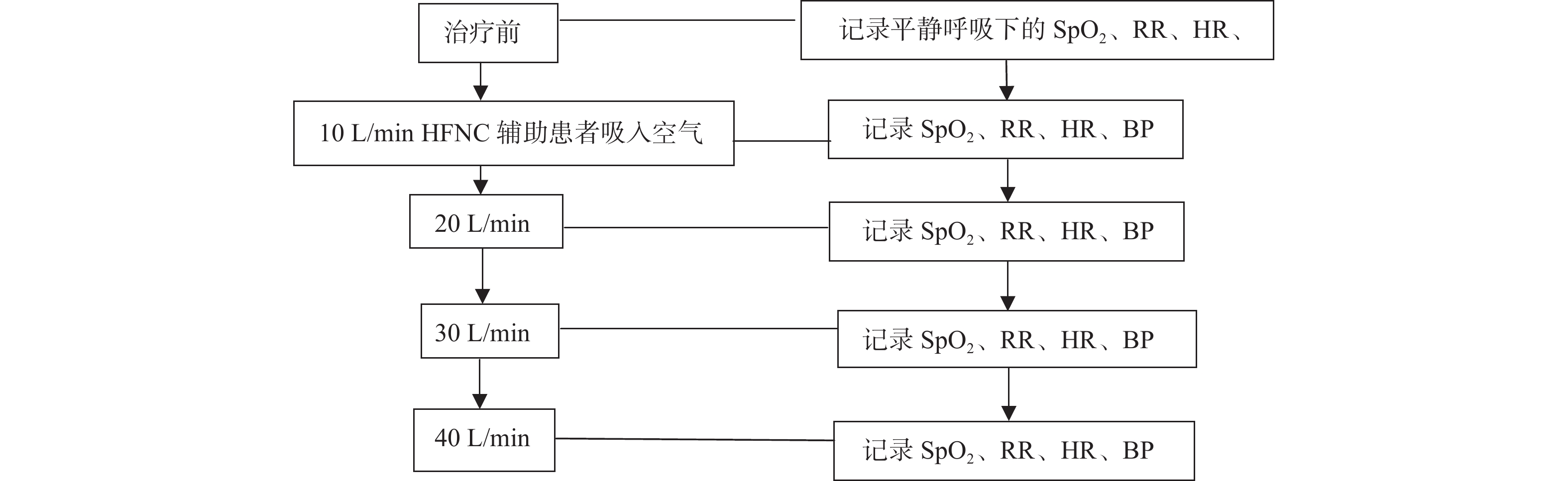

目的 探讨高流量鼻导管氧疗设备在海拔高于2500 m的地区对人体的氧合的改善。 方法 征集从中等海拔高度的昆明(海拔约1891 m)快速进入较高海拔的拉萨(海拔约3650 m)的志愿者,在拉萨使用高流量鼻导管氧疗设备吸入空气,比较使用高流量鼻导管氧疗设备前、后志愿者指端脉搏血氧饱和度(SpO2)、呼吸频率、心率、血压水平。 结果 在高原地区高流量鼻导管氧疗设备运行未出现故障,运转良好。在应用高流量鼻导管氧疗设备进行空气吸入后,随着吸入气体流量的增加,志愿者SpO2改善,呼吸频率减低,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。 结论 高流量鼻导管氧疗设备能改善高海拔地区机体的氧合同时降低呼吸做功,在高海拔性低氧血症的治疗方面存在潜在临床治疗价值。 Abstract:Objective To explore the efficacy of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy on oxygenation in populations at altitudes above 2500 meters. Methods Participants were recruited from medium-altitude Kunming (about 1891 m above sea level) to quickly enter higher altitude Lhasa (about 3650 m above sea level). Participants inhaled air using high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in Lhasa. The pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory rate, heart rate and blood pressure were compared before and after the use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy . Results In high altitude area, the high flow nasal canula oxygen therapy went well and smoothly. After high-flow nasal catheter oxygen therapy, SpO2 improved and respiratory rate decreased with the increase of inhaled gas flow, the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). After using high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy equipment for air inhalation, SpO2 improved and respiratory rate decreased with the increase of inhaled gas flow, the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Conclusion High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy not only improved participants’ oxygenation, it decreased the effort of breathing, and has potential clinical value in the treatment of high-altitude hypoxemia . -

表 1 不同氧流量下温度和吸入氧浓度比较($\bar x \pm s $)

Table 1. Comparison of temperature and oxygen concentration under different oxygen flow ($\bar x \pm s $)

指标 治疗前 10 L/min 20 L/min 30 L/min 40 L/min F P 温度(℃) 36.70 ± 0.47 36.50 ± 1.36 36.83 ± 0.53 36.87 ± 0.35 36.67 ± 0.99 0.932 0.447 FiO2(%) 21.00 ± 0.00 22.33 ± 3.21 22.97 ± 2.16 23.10 ± 2.45 22.90 ± 2.23 0.528 0.664 表 2 治疗前及不同吸氧流量下的氧饱和度、血压、呼吸频率、心率($\bar x \pm s $)

Table 2. Oxygen saturation,blood pressure,respiratory rate,heart rate before treatment and under different oxygen inhalation flow ($\bar x \pm s $)

指标 治疗前 10 L/min 20 L/min 30 L/min 40 L/min F P 收缩压(mmHg) 118.70 ± 15.23 120.90 ± 17.17 118.17 ± 14.22 114.40 ± 16.35 112.90 ± 9.93 1.474 0.213 舒张压(mmHg) 75.87 ± 11.89 74.87 ± 11.77 75.83 ± 8.49 75.23 ± 8.92 77.43 ± 10.35 0.268 0.898 平均动脉压(mmHg) 90.13 ± 11.14 90.23 ± 12.67 89.93 ± 9.99 88.33 ± 10.96 89.27 ± 9.58 0.158 0.959 心率(次/min) 82.47 ± 10.68 85.07 ± 9.86 85.37 ± 10.14 84.77 ± 9.22 81.27 ± 9.68 1.003 0.408 呼吸频率(次/min) 17.43 ± 4.38 14.53 ± 3.60 10.73 ± 3.07 9.20 ± 2.41 8.53 ± 1.83 70.78 < 0.001* SpO2(%) 89.90 ± 3.02 90.73 ± 1.66 91.00 ± 2.51 94.03 ± 2.13 94.97 ± 1.75 71.76 < 0.001* *P < 0.05。 -

[1] Roach R C,Greene E R,Schoene R B,et al. Arterial oxygen saturation for prediction of acute mountain sickness[J]. Aviation,Space,and Environmental Medicine,1998,69(12):1182-1185. [2] Kasic J F,Yaron M,Nicholas R A,et al. Treatment of acute mountain sickness:Hyperbaric versus oxygen therapy[J]. Annals of Emergency Medicine,1991,20(10):1109-1112. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81385-X [3] Grimminger J,Richter M,Tello K,et al. Thin air resulting in high pressure:Mountain sickness and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension[J]. Canadian Respiratory Journal,2017,2017:8381653. [4] Prince T S, Thurman J, Huebner K. Acute mountain sickness[M]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022, 56. [5] Sharma S, Danckers M, Sanghavi D, et al. High flow nasal cannula[M]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022, 205. [6] Riera J,Perez P,Cortes J,et al. Effect of high-flow nasal cannula and body position on end-expiratory lung volume:A cohort study using electrical impedance tomography[J]. Respiratory Care,2013,58(4):589-596. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02086 [7] Onodera Y,Akimoto R,Suzuki H,et al. A high-flow nasal cannula system with relatively low flow effectively washes out CO2 from the anatomical dead space in a sophisticated respiratory model made by a 3D printer[J]. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental,2018,6(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s40635-018-0172-7 [8] Roca O,Perez-Teran P,Masclans J R,et al. Patients with New York Heart Association class III heart failure may benefit with high flow nasal cannula supportive therapy:High flow nasal cannula in heart failure[J]. Journal of Critical Care,2013,28(5):741-746. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.02.007 [9] Ricard J D. High flow nasal oxygen in acute respiratory failure[J]. Minerva Anestesiologica,2012,78(7):836-841. [10] Delorme M,Bouchard P A,Simon M,et al. Effects of high-flow nasal cannula on the work of breathing in patients recovering from acute respiratory failure[J]. Critical Care Medicine,2017,45(12):1981-1988. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002693 [11] Ni Y N,Luo J,Yu H,et al. Can high-flow nasal cannula reduce the rate of endotracheal intubation in adult patients with acute respiratory failure compared with conventional oxygen therapy and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation? A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Chest,2017,151(4):764-775. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.004 [12] Monro-Somerville T,Sim M,Ruddy J,et al. The effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy on mortality and intubation rate in acute respiratory failure:A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Critical Care Medicine,2017,45(4):449-456. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002091 [13] Oczkowski S,Ergan B,Bos L,et al. ERS clinical practice guidelines:High-flow nasal cannula in acute respiratory failure[J]. Eur Respir J,2022,59(4):2101574. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01574-2021 [14] Carratala Perales J M,Llorens P,Brouzet B,et al. High-Flow therapy via nasal cannula in acute heart failure[J]. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia,2011,64(8):723-725. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2010.10.034 [15] Moriyama K,Satoh T,Motoyasu A,et al. High-Flow nasal cannula therapy in a patient with reperfusion pulmonary edema following percutaneous transluminal pulmonary angioplasty[J]. Case Reports in Pulmonology,2014,2014:837612. [16] Atwood C W Jr,Camhi S,Little K C,et al. Impact of heated humidified high flow air via nasal cannula on respiratory effort in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (Miami,Fla),2017,4(4):279-286. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.4.4.2017.0169 [17] Chatila W,Nugent T,Vance G,et al. The effects of high-flow vs low-flow oxygen on exercise in advanced obstructive airways disease[J]. Chest,2004,126(4):1108-1115. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1108 [18] Hernandez G,Vaquero C,Colinas L,et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs noninvasive ventilation on reintubation and postextubation respiratory failure in high-risk patients:A Randomized Clinical Trial[J]. JAMA,2016,316(15):1565-1574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14194 [19] Hernandez G,Vaquero C,Gonzalez P,et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients:A randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA,2016,315(13):1354-1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2711 -

下载:

下载: