Association of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of Calcium Sensitive Receptor Gene with Calcium Nephrolithiasis and Hypercalciuria in Chinese Dai Population

-

摘要:

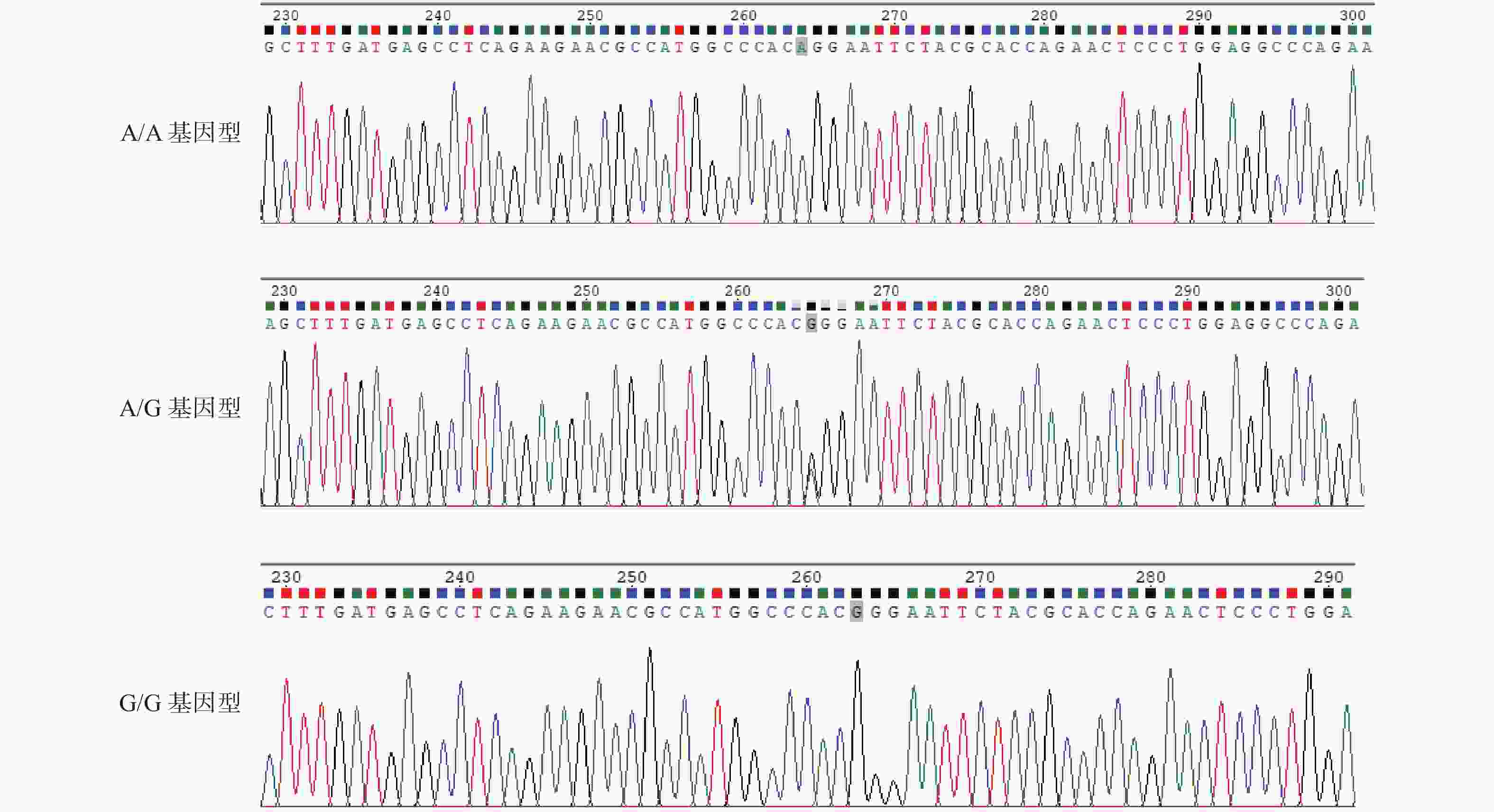

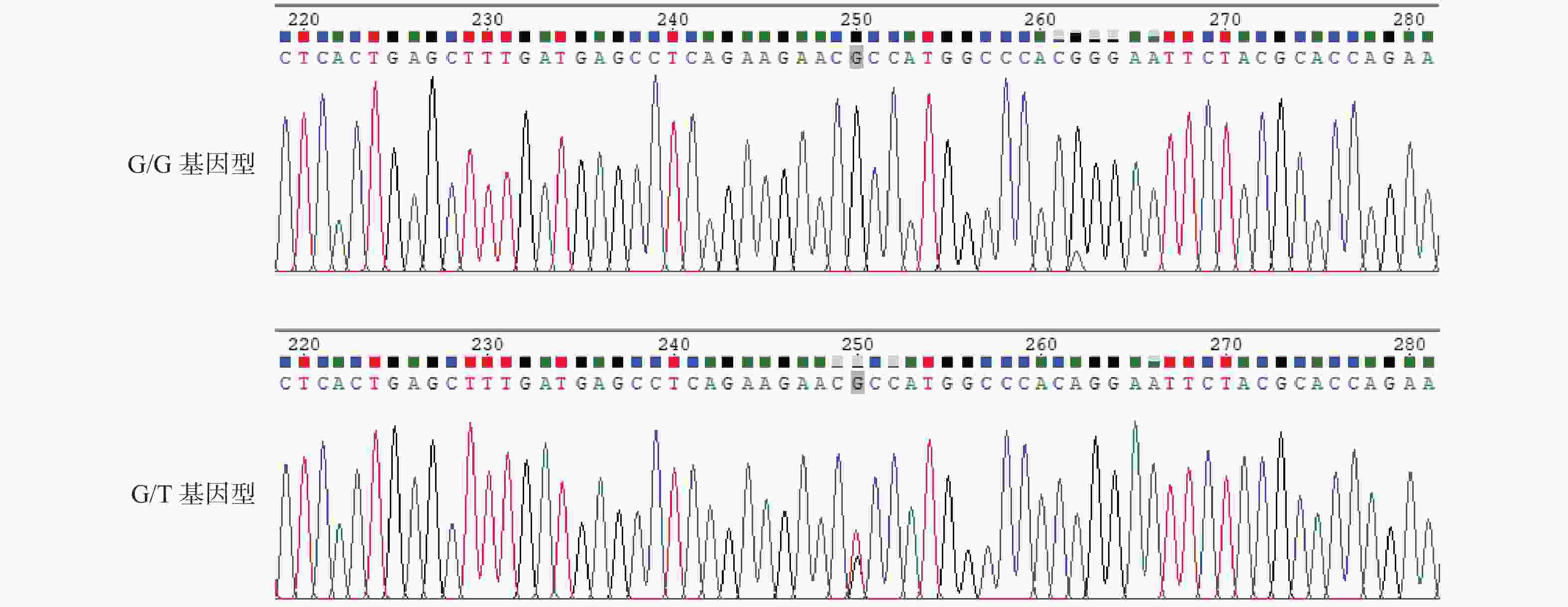

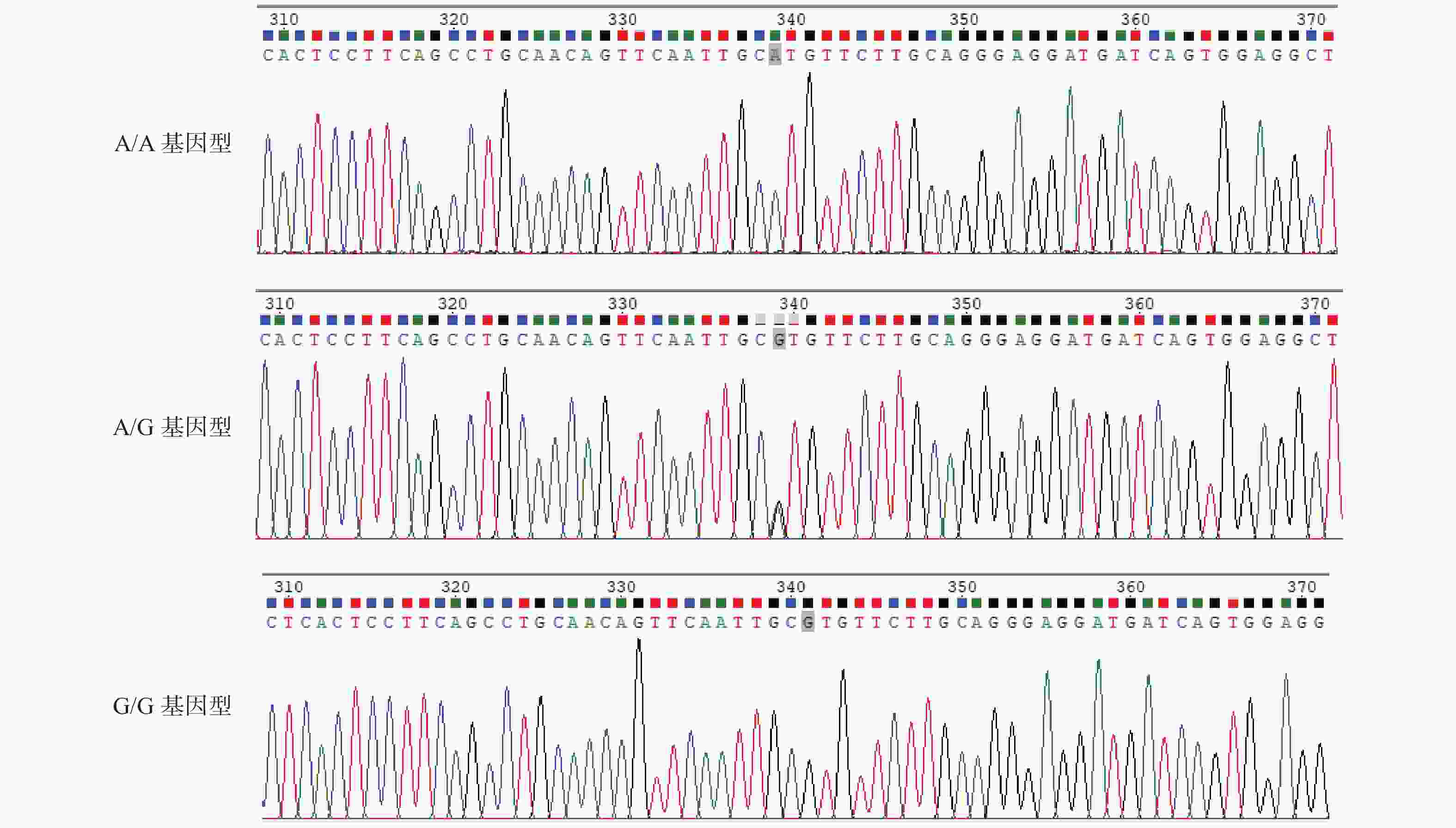

目的 研究云南德宏州傣族人群CaSR基因多态性与含钙肾结石和高钙尿的相关性。 方法 云南德宏州的傣族含钙肾结石患者为实验组,云南德宏州的体检健康傣族人群为对照组,抽静脉血进行CaSR基因3个SNP位点rs7652589、rs1801725、rs1042636测定,结石组研究对象行24 h尿钙值测定,进行基因相关对比分析。 结果 rs7652589位点纯合AA型基因者与AA+GG基因者在含钙肾结石的发生对比分析,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。rs1042636位点的GG型基因者的24 h尿钙值与AA和AG基因型者对比,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。rs7652589位点GG型基因者24 h尿钙与AA和AG型基因者对比,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。 结论 云南德宏州傣族人群中CaSR基因上的rs7652589位点多态性与含钙肾结石和高钙尿的发生有关,rs1042636位点的GG型基因与傣族高钙尿发生相关,rs7652589位点GG型基因可能是该民族发生高钙尿和含钙肾结石的候选基因。 Abstract:Objective To study the association of CaSR gene polymorphism with calcium nephrolithiasis and hypercalciuria in Chinese Dai population. Methods The Dai patients with calcium containing renal calculi in Dehong Prefecture, Yunnan Province, China were selected as the experimental group, and the healthy Dai people in Dehong Prefecture, Yunnan Province were taken as the control group. The venous blood was drawn for the determination of the three SNP loci rs7652589, rs1801725, and rs1042636 of the CaSR gene. The subjects in the stone group were tested for 24-hour urine calcium value, and the gene correlation was analyzed. Results There was a statistical difference between the homozygous AA gene and AA+GG gene at rs7652589 locus in the occurrence of calcium nephrolithiasis (P < 0.05). The 24 h urine calcium value of the GG genotype with rs1042636 locus was significantly different from that of the AA based and AG genotype (P < 0.05). There was a significant difference in 24 h urine calcium between those with GG genotype at rs7652589 locus and those with AA and AG genotype (P < 0.05) Conclusion The rs7652589 polymorphism on the CaSR gene in the Dai population in China is related to the occurrence of calcium nephrolithiasis and hypercalciuria. The GG gene at rs1042636 is related to the occurrence of hypercalciuria in the Dai population. The GG gene at rs7652589 may be a candidate gene for the occurrence of hypercalciuria leading to calcium nephrolithiasis in this ethnic group. -

表 1 研究对象一般信息对比分析

Table 1. Comparative analysis of general information of research subjects

项目 结石组 对照组 χ2/t P 性别 男 87(54.4) 55(63.2) 1.803 0.179 女 73(45.6) 32(36.8) 年龄(岁) 50.63 ± 14.08 51.93 ± 17.58 0.597 0.552 BMI(kg/m2) 24.38 ± 3.33 24.26 ± 3.93 −0.271 0.787 尿pH 5.8 ± 0.6 5.7 ± 0.5 1.3242 0.1867 表 2 引物设计

Table 2. Primer design

引物编号 引物序列 碱基数(bp) Tm值(℃) 扩增产物片段大小(bp) rs7652589-F ATGTGGAAGAAGAAGAGA 18 56 593 rs7652589-R ACGAGAAGAGATAAGTCA 18 56 593 rs1801725-rs1042636-F* CAGCAACGTCTCCCGCAA 18 60 599 rs1801725-rs1042636-R* TGCATTCTCCCTAGCCCAGT 20 60 599 *2个基因位点位置临近,1个引物可以涵盖2个位点。 表 3 哈迪-温伯格平衡检验结果

Table 3. Hardy-Weinberg test

SNP位点 基因型 基因型频数 基因型频率 期望基因型频率 期望基因型频数 χ2 P rs1042636 AA 66 0.268 0.273 67.123 0.082 0.960 AG 125 0.508 0.499 122.754 GG 55 0.224 0.228 56.1123 rs1801725 GG 221 0.898 0.901 221.635 0.705 0.703 GT 25 0.102 0.096 23.730 TT 0 0.000 0.003 0.635 rs7652589 AA 109 0.441 0.444 109.556 0.025 0.987 AG 111 0.449 0.445 109.889 GG 27 0.109 0.112 27.556 表 4 等位基因型频数分析

Table 4. Allelic frequency analysis

基因位点 等位碱基 结石组 对照组 χ2 P rs1042636 A 163 94 0.345 0.557 G 155 80 AA 39 27 1.531 0.465 AG 85 40 GG 35 20 rs1801725 G 302 165 0.005 0.946 T 16 9 GG 143 78 0.005 0.944 GT 16 9 TT 0 0 rs7652589 A 221 108 2.478 0.115 G 99 66 AA 79 30 6.004 0.0497* AG 63 48 GG 18 9 *P < 0.05。 表 5 纯合型与其他基因型频数分析

Table 5. Homozygous and other genotypes frequency analysis

基因位点 基因型 结石组 对照组 χ2 P rs1042636 AA 39 27 1.761 0.415 AG+GG 120 60 AA+AG 124 67 0.013 0.861 GG 35 20 rs1801725 GG 143 78 0.551 0.759 GT+TT 16 9 GG+GT 159 87 N N TT 0 0 rs7652589 AA 79 30 5.069 0.024* AG+GG 81 57 AA+AG 142 78 0.047 0.828 GG 18 9 *P < 0.05。 表 6 单体型分析对应基因位点及位置

Table 6. Haploid analysis corresponding loci and positions

对应基因 SNP位点 位点的位置(GRCh38,3:) CaSR rs1042636 122284922 rs1801725 122284910 rs7652589 122170241 表 7 SNP位点连锁不平衡分析结果(D')

Table 7. Analysis results of linkage disequilibrium at SNP loci (D')

SNP位点 rs7652589 rs1801725 rs1801725 0.082 - rs1042636 0.456 1 表 8 SNP位点连锁不平衡分析结果(r^2)

Table 8. Analysis results of linkage disequilibrium at SNP loci (r^2)

SNP位点 rs7652589 rs1801725 rs1801725 0.001 - rs1042636 0.096 0.049 表 9 2组CaSR基因SNP位点的单倍型分析结果[n(%)]

Table 9. Haploid analysis results of two sets of CaSR gene SNP loci [n(%)]

单体型 结石组(频率) 对照组(频率) χ2 P OR 95%CI AGA 114(35.8) 59(33.9) 0.075 0.785 0.776 0.126~4.775 AGG 39(12.2) 29(16.6) 0.013 0.908 1.115 0.175~7.112 GGA 98(30.8) 46(26.4) 0.142 0.706 0.704 0.114~4.359 GGG 51(16.0) 31(17.8) 0.010 0.922 0.912 0.144~5.764 表 10 2组实验对象高钙尿平均值、高钙尿发病率对比分析表[n(%)/

$\bar x \pm s $ ]Table 10. Comparative analysis of average hypercalciuria and incidence rate of hypercalciuria between two groups [n(%)/

$\bar x \pm s $ ]项目 结石组 对照组 χ2/t P 正常尿钙 97(39) 79(32) 25.061 < 0.001* 高钙尿 63(26) 8(3) 尿钙值(mg) 353 ± 52 196 ± 76 12.84 < 0.001* 草酸钙结石 131(82) - - - 磷酸钙结石 29(18) - - - *P < 0.05。 表 11 结石组各基因型与24 h尿钙值对比分析(

$\bar x \pm s $ )Table 11. Comparative analysis of different genotypes and 24-hour urinary calcium levels in the stone group (

$ \bar x \pm s$ )基因位点 基因型 基因

例数24 h尿钙值

(mg/24 h)t P rs1042636 AA 39 294 ± 44 3.7927 0.0003* AG 85 311 ± 57 2.18 0.0312 GG 35 335 ± 49 rs1801725 GG 143 317 ± 72 0.6355 0.526 GT 16 305 ± 68 TT 0 0 rs7652589 AA 79 207 ± 48 11.5477 < 0.0001* AG 63 342 ± 61 0.7587 0.4503 GG 18 354 ± 52 *P < 0.05。 -

[1] Sorokin I,Mamoulakis C,Miyazawa K,et al. Epidemiology of stone disease across the world[J]. World J Urol,2017,35(9):1301-1320. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2008-6 [2] Khan A. Prevalence,pathophysiological mechanisms and factors affecting urolithiasis[J]. Int Urol Nephrol,2018,50(5):799-806. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-1849-2 [3] Bishop K,Momah T,Ricks J. Nephrolithiasis[J]. Prim Care,2020,47(4):661-671. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2020.08.005 [4] Vladimirovna F T,Faridovich K C,Igorevich R V,et al. Genetic factors of polygenic urolithiasis[J]. Urologia,2020,87(2):57-64. doi: 10.1177/0391560319898375 [5] Youssef R F,Martin J W,Sl K,et al. Rising occurrence of hypocitraturia and hyperoxaluria associated with increasing prevalence of stone disease in calcium kidney stone formers[J]. Scand J Urol,2020,54(5):426-430. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2020.1794955 [6] Negri A L,Delvalle E E,et al. Role of claudins in idiopathic hypercalciuria and renal lithiasis[J]. Int Urol Nephrol,2022,54(9):2197-2204. doi: 10.1007/s11255-022-03119-2 [7] Shin S,Ibeh C L,Awuah B E,et al. Hypercalciuria switches Ca(2+) signaling in proximal tubular cells,induces oxidative damage to promote calcium nephrolithiasis[J]. Genes Dis,2022,9(2):531-548. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2021.04.006 [8] Mohammadi A,Shabestari A N,Baghdadabad L Z,et al. Genetic polymorphisms and kidney stones around the globe: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Front Genet,2022,13(4):908-913. [9] Halbritter J. Genetics of kidney stone disease-polygenic meets monogenic[J]. Nephrol Ther,2021,17S(2):S88-S94. [10] Litvinova M M,Khafizov K,Korchagin V I,et al. Association of CASR,CALCR,and ORAI1 genes polymorphisms with the calcium urolithiasis development in Russian population[J]. Front Genet,2021,12(10):621-629. [11] Vezzoli G,Macrina L,Magni G,et al. Calcium-sensing receptor: Evidence and hypothesis for its role in nephrolithiasis[J]. Urolithiasis,2019,47(1):23-33. doi: 10.1007/s00240-018-1096-0 [12] Li H,Zhang J,Long J,et al. Calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphism (rs7652589) is associated with calcium nephrolithiasis in the population of Yi nationality in Southwestern China[J]. Ann Hum Genet,2018,82(5):265-271. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12249 [13] Ding Q,Fan B,Shi Y,et al. Calcium-sensing receptor genetic polymorphisms and risk of developing nephrolithiasis in a Chinese population[J]. Urol Int,2017,99(3):331-337. doi: 10.1159/000451006 [14] Veser J,Jahrreiss V,Seitz C. Innovations in urolithiasis management[J]. Curr Opin Urol,2021,31(2):130-134. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000850 [15] Mayans L. Nephrolithiasis[J]. Prim Care,2019,46(2):203-212. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2019.02.001 [16] Alexander R T,Fuster D G,Dimke H,et al. Mechanisms underlying calcium nephrolithiasis[J]. Annual Review of Physiology,2022,84(1):559-583. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-052521-121822 [17] Liu Y,Chen Y,Liao B,et al. Epidemiology of urolithiasis in Asia[J]. Asian J Urol,2018,5(4):205-214. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2018.08.007 [18] 李康健, 莫茵, 申吉泓, 等. 维生素D受体基因SNP位点rs7975232和rs731236与云南彝族人群特发性低枸橼酸尿症的关系[J] , 广东医学, 2016, 37(17): 2580-2584. [19] Li K,Luo Y,Mo Y,et al. Association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and idiopathic hypocitraturia in a Chinese Bai population[J]. Urolithiasis,2019,47(3):235-242. doi: 10.1007/s00240-018-1069-3 [20] Sangkaew B,Nuinoon M,Jeenduang N. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with serum 25(OH)D levels and metabolic syndrome in Thai population[J]. Gene,2018,659(3):59-66. [21] Howles S A,Thakker R V. Genetics of kidney stone disease[J]. Nat Rev Urol,2020,17(7):407-421. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0332-x [22] Mandal A,Khandelwal P,Geetha T S,et al. Metabolic and genetic evaluation in children with nephrolithiasis[J]. Indian J Pediatr,2022,98(22):34-42. [23] Hemminki K,Hemminki O,Forsti A,et al. Familial risks between urolithiasis and cancer[J]. Sci Rep,2018,8(1):3083. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21410-0 [24] Goldfarb D S,Avery A R,Beara-lasic L,et al. A twin study of genetic influences on nephrolithiasis in women and men[J]. Kidney Int Rep,2019,4(4):535-540. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.11.017 [25] Tsuji T,Hiroyuki A,Uraki S,et al. Autosomal dominant hypocalcemia with atypical urine findings accompanied by novel CaSR gene mutation and VitD deficiency[J]. J Endocr Soc,2021,5(3):190-195. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa190 [26] Hannan F M,Kallay E,Chang W,et al. The calcium-sensing receptor in physiology and in calcitropic and noncalcitropic diseases[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol,2018,15(1):33-51. [27] Chavez-abiega S,Mos I,Centeno P P,et al. Sensing extracellular calcium - An insight into the structure and function of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR)[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol,2020,11(31):1031-1063. [28] Ewers M,Canaff L,Weh A E,et al. The three common polymorphisms p. A986S,p. R990G and p. Q1011E in the calcium sensing receptor (CASR) are not associated with chronic pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology,2021,21(7):1299-1304. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2021.08.008 [29] Guo S,Chi A W,Wang H,et al. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) contributes to the development of hypercalciuria by sensitizing VDR target genes to vitamin D in a genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming (GHS) rat model[J]. Genes Dis,2022,9(3):797-806. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.09.001 [30] Vahe C,Benomar K,Espiard S,et al. Diseases associated with calcium-sensing receptor[J]. Orphanet J Rare Dis,2017,12(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0570-z [31] Guha M,Bankura B,Ghosh S,et al. Polymorphisms in CaSR and CLDN14 genes associated with increased risk of kidney stone disease in patients from the eastern part of India[J]. PLoS One,2015,10(6):130-139. [32] Ali F T,El-azeem E M A,Hekal H F A,et al. Association of TRPV5,CASR,and CALCR genetic variants with kidney stone disease susceptibility in Egyptians through main effects and gene-gene interactions[J]. Urolithiasis,2022,50(6):701-710. doi: 10.1007/s00240-022-01360-z [33] Grzegorzewska A E,Paciorkowski M,Mostowska A,et al. Associations of the calcium-sensing receptor gene CASR rs7652589 SNP with nephrolithiasis and secondary hyperparathyroidism in haemodialysis patients[J]. Sci Rep,2016,6:351-388. [34] Taguchi K,Yasui T,Milliner D S,et al. Genetic risk factors for idiopathic urolithiasis: A systematic review of the literature and causal network analysis[J]. Eur Urol Focus,2017,3(1):72-81. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.04.010 [35] Zhou H,Huang H,You Z,et al. Genetic polymorphism (rs6776158) in CaSR gene is associated with risk of nephrolithiasis in Chinese population[J]. Medicine (Baltimore),2018,97(45):130-137. [36] Gillion V,Devuyst O. Genetic variation in claudin-2,hypercalciuria,and kidney stones[J]. Kidney Int,2020,98(5):1076-1078. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.055 [37] Ferre N,Parada E,Balaguer A,et al. Pharmacological interventions for preventing complications in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria: A systematic review[J]. Nefrologia (Engl Ed),2021,92(5):1007-1016. -

下载:

下载: