Study on Serum Markers of Intestinal Barrier Damage in Heroin Addicts at Different Withdrawal Times

-

摘要:

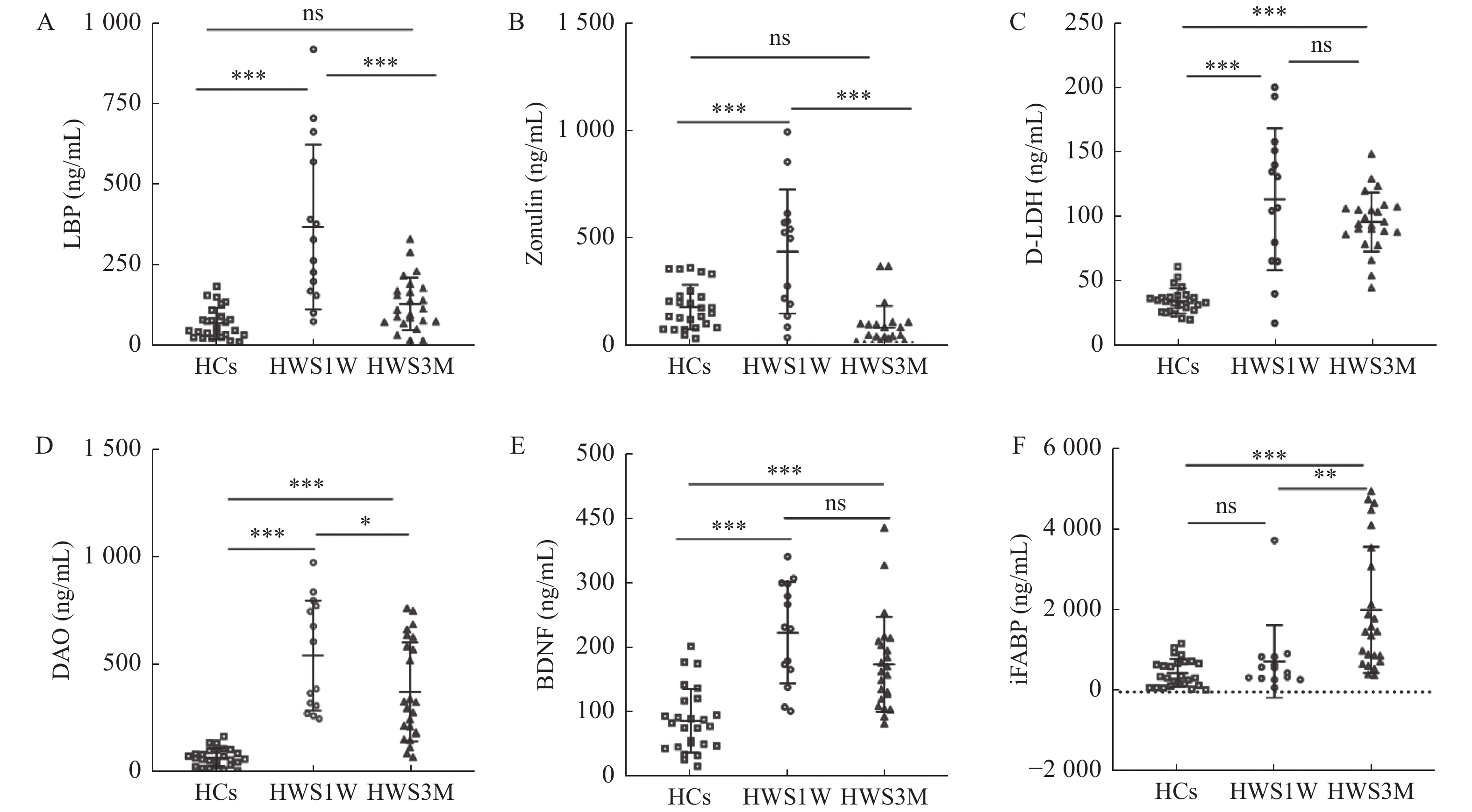

目的 分析不同戒断时间内肠道屏障损伤标志物的变化,研究海洛因戒断后肠屏障损伤的机制,为海洛因戒断后精神症状改变和肠屏障之间的关系提供新的方向。 方法 招募14名海洛因戒断1周(HWS1W),24名海洛因戒断3月(HWS3M)的人群和26名健康者为对照组(HCs),用ELISA法测定血清iFABP、D-LDH、DAO、LBP、Zonulin和BDNF。 结果 HWS1W组的血清D-LDH、DAO、LBP、Zonulin和BDNF水平均明显高于HCs组(P < 0.001)。HWS3M组的血清iFABP、D-LDH、DAO和BDNF明显高于HCs组(P < 0.001)。DAO在海洛因戒断1周时明显升高,3个月时明显降低,但仍高于健康对照组(P < 0.001)。iFABP在急性戒断期(1周)没有变化,但在戒断的3个月左右增加。LBP和Zonulin在海洛因戒断组约1周内明显增加,但在HWS3M组和HCs组之间差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。HWS1W组和HWS3M组的D-LDH和BDNF的水平明显增加(P < 0.001)。 结论 海洛因戒断1周和3个月均发生肠屏障功能损伤。戒断1周后,肠屏障损伤可能与肠道菌群紊乱、紧密连接蛋白变化、肠道炎症和肠上皮完整性损伤有关。戒断3个月后,肠屏障损伤更可能是肠屏障上皮持续损伤造成的。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the mechanisms of intestinal barrier damage after heroin withdrawal by analyzing changes in markers of intestinal barrier damage at different withdrawal times, providing a new direction for the relationship between altered psychiatric symptoms and the intestinal barrier after heroin withdrawal. Methods 14 1-week heroin withdrawal subjects (HWS1W), 24 3-months heroin withdrawal subjects (HWS3M) and 26 healthy controls (HCs) were recruited, and serum iFABP, D-LDH, iFABP, DAO, LBP, Zonulin, BDNF and D-LDH were determined by ELISA. Results Serum D-LDH, DAO, LBP, Zonulin and BDNF levels in HWS1W group were significantly higher than those in HCs (P < 0.001). Serum iFABP, D-LDH, DAO, and BDNF in HWS3M group were significantly higher than those in HCs group (P < 0.001). DAO increased significantly at 1 week of heroin withdrawal and decreased significantly at 3 months, but was still higher than the healthy control group (P < 0.001). iFABP showed no change in the acute withdrawal period (1 week), but increased at about 3 months of withdrawal. LBP and Zonulin increased significantly in the heroin abstention group for about one week, but there was no significant difference between the HWS3M group and the HCs group (P > 0.05). The levels of D-LDH and BDNF were significantly increased in HWS1W and HWS3M groups (P < 0.001). Conclusions The present study showed that intestinal barrier dysfunction occurred both 1 week and 3 months after heroin withdrawal. After 1 week of abstinence, intestinal barrier damage may be associated with intestinal flora disorder, changes in tight junction proteins, intestinal inflammation and intestinal epithelial integrity damage. After 3 months of abstinence, intestinal barrier damage is more likely to result from persistent damage to the intestinal barrier epithelium. -

表 1 HWS1W、HWS3M、HCs 3组基本情况比较(

$\bar x \pm s $ )Table 1. Comparison of the three groups of basic conditions (

$\bar x \pm s $ )基本情况 HWS1W(n = 14) HWS3M(n = 24) HCs(n = 26) F/t P 年龄(岁) 35.6 ± 6.0 45.7 ± 6.4▲# 36.7 ± 12.3 7.535 0.001* 吸毒时间(a) 14.6 ± 4.3 17.4 ± 5.8 − 1.570 0.125 BMI(kg/m2) 20.3 ± 2.1△☆ 22.6 ± 2.4 23.1 ± 3.2 4.952 0.010* HWS1W:海洛因成瘾戒断1周组;HWS3M:海洛因成瘾戒断3月组;HCs:健康对照组;BMI:身体质量指数。*P < 0.05 ;与HWS1W组比较,▲P < 0.05;与HCS组比较,#P < 0.05;与HWS3M组比较,△P < 0.05;与HWS3M组比较,☆P < 0.05。 表 2 HWS1W患者肠屏障损伤血清标志物的相关性及其与HWS1W基本情况的相关性[r(P)]

Table 2. Correlation of serum markers of intestinal barrier injury in Group HWS1W,Correlation between serum markers of intestinal barrier injury and basic conditions in Group HWS1W [r(P)]

项目 D-LDH BDNF DAO LBP Zonulin 年龄 −0.346(0.225) −0.028(0.925) −0.209(0.474) −0.1(0.734) 0.002(0.995) 吸毒时间 −0.332(0.247) −0.339(0.236) −0.17(0.561) −0.014(0.961) −0.297(0.303) BMI 0.101(0.731) 0.275(0.342) 0.208(0.475) 0.096(0.743) 0.123(0.675) D-LDH 1(0.000*) −0.358(0.208) 0.476(0.085) −0.235(0.419) −0.085(0.773) BDNF −0.358(0.208) 1(0.000*) −0.431(0.124) 0.38(0.180) 0.195(0.503) DAO 0.476(0.085) −0.431(0.124) 1(0.000*) −0.356(0.212) 0.279(0.335) LBP −0.235(0.419) 0.38(0.180) −0.356(0.212) 1(0.000*) −0.583(0.029*) Zonulin −0.085(0.773) 0.195(0.503) 0.279(0.335) −0.583(0.029*) 1(0.000*) *P < 0.05。 表 3 HWS3M患者肠屏障损伤血清标志物的相关性及其与HWS3M人体测量数据的相关性[r(P)]

Table 3. Correlation of serum markers of intestinal barrier injury in Group HWS3M;Correlation between serum markers of intestinal barrier injury and basic conditions in Group HWS3M [r(P)]

项目 iFABP D-LDH DAO BDNF 年龄 −0.007(0.976) −0.179(0.414) −0.174(0.426) −0.384(0.070) 吸毒时间 −0.537(0.008*) 0.236(0.277) 0.065(0.770) −0.009(0.969) BMI −0.191(0.383) 0.039(0.860) −0.209(0.339) −0.016(0.942) iFABP 1(0.000*) −0.151(0.492) −0.029(0.896) 0.012(0.955) D-LDH −0.151(0.492) 1(0.000*) 0.453(0.030*) −0.322(0.134) DAO −0.029(0.896) 0.453(0.030*) 1(0.000*) −0.149(0.497) BDNF 0.012(0.955) −0.322(0.134) −0.149(0.497) 1(0.000*) *P < 0.05。 -

[1] Demaret I,Lemaître A,Ansseau M. Heroin[J]. Revue Medicale de Liege,2013,68(5-6):287-293. [2] Tolomeo S,Steele J D,Ekhtiari H,et al. Chronic heroin use disorder and the brain: Current evidence and future implications[J]. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry,2021,111(2):110148. [3] Yang J,Xiong P,Bai L,et al. The association of altered gut microbiota and intestinal mucosal barrier integrity in mice with heroin dependence[J]. Frontiers in Nutrition,2021,11(8):765414. [4] Camilleri M,Madsen K,Spiller R,et al. Intestinal barrier function in health and gastrointestinal disease[J]. Neurogastroenterology and Motility:The Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society,2012,24(6):503-512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01921.x [5] Takiishi T,Fenero C I M,Câmara N O S. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life[J]. Tissue Barriers,2017,5(4):e1373208. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2017.1373208 [6] Fasano A. Intestinal permeability and its regulation by zonulin: diagnostic and therapeutic implications[J]. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology:The Official Clinical Practice Journal of the American Gastroenterological Association,2012,10(10):1096-1100. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.012 [7] Seethaler B,Basrai M,Neyrinck A M,et al. Biomarkers for assessment of intestinal permeability in clinical practice[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol,2021,321(1):G11-g17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00113.2021 [8] Wang W,Uzzau S,Goldblum S. E,et al. Human zonulin,a potential modulator of intestinal tight junctions[J]. Journal of Cell Science,2000,113(24):4435-4440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4435 [9] El Asmar R,Panigrahi P,Bamford P,et al. Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure[J]. Gastroenterology,2002,123(5):1607-1615. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36578 [10] Vanuytsel T,Vermeire S,Cleynen I,et al. The role of Haptoglobin and its related protein,Zonulin,in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Tissue Barriers,2013,1(5):e27321. doi: 10.4161/tisb.27321 [11] Sapone A,de Magistris L,Pietzak M,et al. Zonulin upregulation is associated with increased gut permeability in subjects with type 1 diabetes and their relatives[J]. Diabetes,2006,55(5):1443-1449. doi: 10.2337/db05-1593 [12] Moreno-Navarrete J. M,Sabater M,Ortega F,et al. Circulating zonulin,a marker of intestinal permeability,is increased in association with obesity-associated insulin resistance[J]. PloS One,2012,7(5):e37160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037160 [13] Besnard P,Niot I,Poirier H,et al. New insights into the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) family in the small intestine[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry,2002,239(1-2):139-147. [14] Yu Y B,Zhao D Y,Qi Q Q,et al. BDNF modulates intestinal barrier integrity through regulating the expression of tight junction proteins[J]. Neurogastroenterology and Motility:the Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society,2017,29(3):145-152. [15] Lommatzsch M,Braun A,Mannsfeldt A,et al. Abundant production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor by adult visceral epithelia. Implications for paracrine and target-derived Neurotrophic functions[J]. The American Journal of Pathology,1999,155(4):1183-1193. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65221-2 [16] Chen J Y,Yu J C,Cao J P,et al. Abstinence following a motivation-skill-desensitization-mental energy intervention for heroin dependence: A three-year follow-up result of a randomized controlled trial[J]. Curr Med Sci,2019,39(3):472-482. doi: 10.1007/s11596-019-2062-y [17] Wang L B,Xu L L,Chen L J,et al. Methamphetamine induces intestinal injury by altering gut microbiota and promoting inflammation in mice[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology,2022,443(1):116011. [18] Li Y,Kong D,Bi K,et al. Related effects of methamphetamine on the intestinal barrier via cytokines,and potential mechanisms by which methamphetamine may occur on the brain-gut axis[J]. Frontiers in Medicine,2022,9(2):783121. [19] Shen S,Zhao J,Dai Y,et al. Methamphetamine-induced alterations in intestinal mucosal barrier function occur via the microRNA-181c/ TNF-α/tight junction axis[J]. Toxicology Letters,2020,321(1):73-82. [20] Na K S,Jung H Y,Kim Y K. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the neuroinflammation and neurogenesis of schizophrenia[J]. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry,2014,48(3):277-286. [21] Ohlsson L,Gustafsson A,Lavant E,et al. Leaky gut biomarkers in depression and suicidal behavior[J]. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,2019,139(2):185-193. doi: 10.1111/acps.12978 [22] Simpson C A,Diaz-Arteche C,Eliby D,et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression - A systematic review[J]. Clinical Psychology Review,2021,83(4):101943. [23] Foster J A,McVey Neufeld K A. Gut-brain axis: How the microbiome influences anxiety and depression[J]. Trends in Neurosciences,2013,36(5):305-312. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005 [24] Lach G,Schellekens H,Dinan T. G,et al.,Anxiety,depression,and the microbiome: A role for gut peptides[J]. Neurotherapeutics:the Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics,2018,15(1):36-59. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0585-0 [25] Parker A,Fonseca S,Carding S. R. Gut microbes and metabolites as modulators of blood-brain barrier integrity and brain health[J]. Gut Microbes,2020,11(2):135-157. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2019.1638722 [26] Braniste V,Al-Asmakh M,Kowal C,et al. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice[J]. Science Translational Medicine,2014,6(263):158-263. [27] Fröhlich E E,Farzi A,Mayerhofer R,et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: Analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication[J]. Brain,Behavior,and Immunity,2016,56(4):140-155. [28] Parekh S. V,Paniccia J. E,Adams L. O,et al. Hippocampal TNF-α signaling mediates heroin withdrawal-enhanced fear learning and withdrawal-induced weight loss[J]. Molecular Neurobiology,2021,58(6):2963-2973. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02322-z [29] Fasano A. Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: The biological door to inflammation,autoimmunity,and cancer[J]. Physiological Reviews,2011,91(1):151-175. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2008 [30] Voigt R M,Raeisi S,Yang J,et al. Systemic brain derived neurotrophic factor but not intestinal barrier integrity is associated with cognitive decline and incident Alzheimer’s disease[J]. PloS One,2021,16(3):e0240342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240342 -

下载:

下载: