A Study on Prognostic Value of Cellular Immunological Indicators in Omicron Variant Infected Elderly Severe Patients

-

摘要:

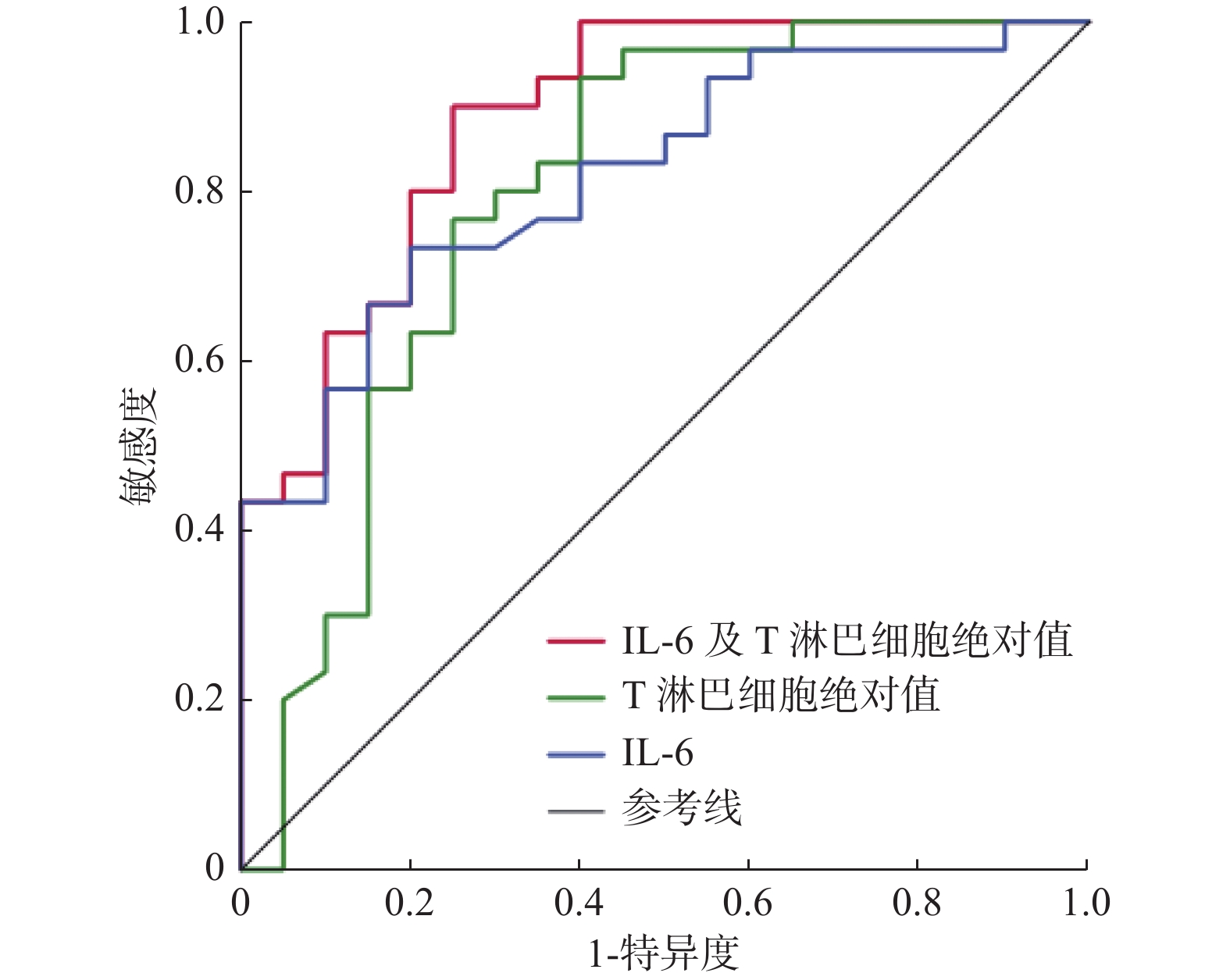

目的 探讨奥密克戎变异株老年重症感染者的临床细胞免疫学指标特征及其与预后的关系。 方法 回顾性分析2022年12月至2023年2月昆明医科大学第一附属医院老年ICU收治的53例奥密克戎变异株感染者的临床资料,将其分为存活组(n = 22)、死亡组(n = 31),进行组间比较。采用Logistic分析确定奥密克戎变异株老年重症感染者的预后因素并构建ROC曲线。 结果 多因素Logistic分析显示IL-6升高(P = 0.043)和T淋巴细胞绝对值下降(P = 0.011)是预后的独立危险因素。使用IL-6、T淋巴细胞绝对值和二者联合进行Logistic回归分析所得到的值分别构建ROC曲线,得到的曲线下面积分别为0.818、0.796和0.887。 结论 IL-6升高及T淋巴细胞绝对值下降是奥密克戎变异株老年重症感染者预后的独立危险因素。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the characteristics of clinical cellular immunity and its relationship with prognosis in elderly patients with severe infection caused by Omicron variant. Methods The clinical data of 53 patients with Omicron variant infection admitted to the geriatric Intensive Care Unit of the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University from December 2022 to February 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were divided into 22 survival cases and 31 death cases for comparison between the two groups. Logistic analysis is adopted to define the omicron variants of elderly severe infections prognostic factors and construct the ROC curve. Results Multivariate logistic analysis revealed that the independent risk factors were elevated IL-6(P = 0.043) and decreased absolute T lymphocyte count(P = 0.011).AUC value of ROC of IL-6, absolute T lymphocyte count and IL-6 combined with absolute T lymphocyte count was 0.818, 0.796 and 0.887. Conclusion Elevated IL-6 and decreased absolute T lymphocyte count are independent risk factors for elderly severe patients with Omicron variant infections. -

Key words:

- Omicron variant /

- Prognosis /

- Cellular immunological indicators

-

表 1 2组患者基线资料比较[M(P25,P75)/n(%)/ $\bar x \pm s$]

Table 1. Comparison of baseline data between the two groups [M(P25,P75)/n(%)/ $\bar x \pm s$]

变量 死亡组

(n = 31)存活组

(n = 22)t/z/χ2 P 年龄(岁) 77.00(64.00,89.00) 78.50(69.25,84.50) −0.09 0.814 性别 男 26(83.87) 15(68.18) 1.808 0.179 女 5(16.13) 7(31.82) 高血压 19(61.29) 10(45.45) 1.302 0.254 糖尿病 13(41.93) 9(40.91) 0.006 0.940 慢性肾病 2(6.45) 0(0.00) − 0.505 冠心病 3(9.68) 3(13.64) − 0.683 脑血管

意外6(19.35) 1(4.54) − 0.218 慢阻肺 3(9.68) 0(0.00) − 0.258 病情分级 重型 2(6.45) 8(36.36) 5.694 0.017* 危重型 29(93.55) 14(63.64) APACHEII评分 17.27±6.35 13.91±6.04 1.948 0.057 SOFA

评分8.58±2.55 6.54±2.97 2.671 0.010* GCS评分 8.00(6.00,12.00) 13.50(8.50,15.00) −2.490 0.013* APACHE-II评分:急性生理与慢性健康评分;SOFA评分:序贯器官衰竭评估评分;GCS评分:格拉斯哥昏迷评分;存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 2 2组患者一般实验室检查比较[ M(P25,P75)/ $\bar x \pm s $]

Table 2. Comparison of laboratory test results between the two groups [ M(P25,P75)/ $\bar x \pm s $]

变量 死亡组 (n = 31) 存活组 (n = 22) z/t P 核酸检测CT值 29.00(25.99,34.00) 32.00(28.00,36.54) −1.293 0.196 血乳酸(mmol/L) 2.10(1.40,3.10) 1.50(1.15,1.95) −2.006 0.045* pH值 7.41(7.34,7.46) 7.45(7.41,7.49) −2.541 0.011* OI(mmHg) 102.00(66.00,174.00) 201.00(167.75,278.00) −3.448 0.001* 白细胞计数(x109/L) 12.10±6.53 11.00±6.65 0.598 0.553 中性粒细胞百分比(%) 91.50(86.40,94.60) 86.85(76.30,92.92) −1.995 0.046* 中性粒细胞绝对值(x109/L) 10.95±5.89 9.66±6.51 0.751 0.456 淋巴细胞绝对值(x109/L) 0.37(0.26,0.78) 0.79(0.50,1.03) −2.528 0.011* 血小板计数(x109/L) 180.58±69.64 200.50±106.56 −0.824 0.414 中性粒细胞淋巴细胞比值 23.14(11.65,39.97) 12.48(4.86,24.53) −2.445 0.014* 血小板淋巴细胞比值 425.00(246.88,682.61) 272.42(175.36,408.03) −1.769 0.077 PCT(ng/mL) 0.45(0.19,2.02) 0.24(0.09,0.41) −2.048 0.041* HS-CRP(mg/L) 79.60(38.80,122.10) 45.80(23.70,139.97) −0.774 0.439 血清铁蛋白(ng/L) 1410.50 (859.50,2662.20 )1340.00 (626.27,2285.00 )−0.614 0.553 PT(s) 14.60(13.40,17.10) 13.90(13.27,14.90) −1.201 0.230 APTT(s) 37.60(34.50,40.60) 39.35(36.17,44.72) −1.110 0.267 D二聚体(mg/L) 2.27(1.41,7.31) 1.64(0.99,4.36) −1.379 0.168 ALT(U/L) 22.50(12.45,40.67) 28.70(18.70,91.33) −1.345 0.179 AST(U/L) 38.60(26.21,67.20) 36.44(20.57,73.35) −0.469 0.639 尿素(mmol/L) 10.64(7.05,21.07) 8.00(5.17,15.20) −1.462 0.144 肌酐(μmol/L) 108.10(74.80,267.20) 88.80(72.21,88.80) −1.468 0.134 ALB(g/L) 32.00(28.90,33.90) 35.00(31.57,37.67) −1.977 0.048* 血糖(mmol/L) 9.52(7.01,13.80) 8.05(5.79,11.90) −1.278 0.201 cTnI(ng/mL) 0.13(0.04,0.38) 0.04(0.02,0.18) −1.462 0.144 BNP(pg/mL) 176.38(116.29,409.44) 78.60(37.54,209.50) −1.986 0.047* OI:氧合指数;PCT:降钙素原;HS-CRP:超敏C反应蛋白;PT:凝血酶原时间;APTT:活化部分凝血活酶时间;ALT:谷丙转氨酶;AST:谷草转氨酶;ALB:白蛋白;cTnI:肌钙蛋白I;BNP:脑钠肽;存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 3 2组患者12项细胞因子检测比较[M(P25,P75)]

Table 3. Comparison of 12 cytokines between the two groups[M(P25,P75)]

变量 死亡组(n = 31) 存活组(n = 22) z P IL-1β(pg/mL) 1.99(1.41,3.23) 1.24(1.41,3.23) −1.772 0.076 IL-2(pg/mL) 1.46(1.23,1.75) 1.01(0.76,1.61) −2.779 0.005* IL-4(pg/mL) 1.03(0.85,1.27) 0.86(0.30,1.11) −1.791 0.073 IL-5(pg/mL) 1.53(1.32,2.67) 1.60(1.23,2.05) −0.299 0.765 IL-8(pg/mL) 5.30(1.76,37.53) 6.89(1.04,19.33) −0.718 0.473 IL-10(pg/mL) 3.27(1.95,8.30) 1.70(1.45,2.70) −2.798 0.005* IL-6(pg/mL) 64.43(16.84,206.14) 11.78(4.16,28.38) −3.730 < 0.001* IL-12P70(pg/mL) 0.97(0.68,1.25) 0.58(0.38,0.99) −2.462 0.014* IL-17(pg/mL) 3.95(0.38,11.85) 1.20(0.65,2.93) −0.774 0.439 IFN-α(pg/mL) 1.06(0.64,1.91) 0.60(0.39,1.62) −1.809 0.070 IFN-γ(pg/mL) 1.15(0.56,1.86) 1.26(0.78,2.86) −1.203 0.229 TNF-α(pg/mL) 1.04(0.75,1.50) 0.84(0.54,1.33) −1.240 0.215 IL:白细胞介素;IFN:可溶性二聚体细胞因;TNF:肿瘤坏死因子;存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 4 2组患者T淋巴细胞亚群检测比较[M(P25,P75)/ $ \bar x \pm s $]

Table 4. Comparison of T lymphocyte subsets examination data between the two groups[M(P25,P75)/ $ \bar x \pm s $]

变量 死亡组(n = 31) 存活组(n = 22) t/z P 淋巴细胞绝对值(个/μL) 399.00(295.00,726) 714.00(337.00, 1024.50 )−3.594 < 0.001* T淋巴细胞绝对值(个/μL) 302.00(217.00,455.50) 395.00(216.00,552.00) −3.515 < 0.001* 细胞毒/抑制性T细胞绝对值(个/μL) 102.50(60.00,455.00) 120.00(93.00,230.00) −2.634 0.008* Th辅助性T细胞绝对值(个/μL) 164.00(112.00,236.00) 202.00(107.00,312.00) −2.971 0.003* NK细胞绝对值(个/μL) 67.50(34.25,154.50) 154.00(52.50,219.50) −1.709 0.087 B淋巴细胞绝对值(个/μL) 74.50(24.00,148.75) 51.00(28.00,187.50) −1.567 0.117 CD4/CD8比值 1.86±0.89 1.80±1.28 −0.184 0.855 存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 5 2组患者感染相关免疫细胞比较[ $\bar x \pm s$]

Table 5. Comparison of infection-related immune cells data between the two groups[ $ \bar x \pm s$ ]

变量 死亡组(n = 31) 存活组(n = 22) t P CD64感染指数 4.80±0.90 2.40±1.47 −4.1 < 0.001* HLA-DR(%) 36.78±21.09 66.56±24.60 2.8 0.01* Treg(%) 9.34±1.65 11.33±3.54 1.47 0.16 HLA-DR:人类白细胞抗原DR; Treg:调节性T淋巴细胞;存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 6 2组患者治疗措施比较[n(%),M(P25,P75)]

Table 6. Comparison of treatment measures data between the two groups[n(%),M(P25,P75)]

变量 死亡组(n=31) 存活组(n=22) z/χ2 P 使用血管活性药物 30(96.77) 9(40.90) 20.661 <0.001* 使用激素 26(83.87) 17(77.27) 0.062 0.724 使用免疫调节剂 20(64.52) 16(72.73) 0.402 0.526 使用抗凝药物 27(87.09) 18(81.81) − 0.705 使用机械通气 29(93.55) 17(77.27) − 0.113 使用俯卧位通气 6(19.35) 10(45.45) 4.159 0.042* PEEP(cmH2O) 8.00(6.00,10.00) 7.00(6.00,7.00) −0.740 0.486 PEEP:呼气末正压;存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 7 免疫指标多因素Logistic回归分析

Table 7. The multivariate Logistic regression analysis of immune indicators

变量 OR(95%CI) P IL-6(pg/mL) 1.023(1.101~1.047) 0.043* T淋巴细胞绝对值(个/μL) 0.994(0.989~0.999) 0.011* IL:白细胞介素;存活组与死亡组组间比较,*P < 0.05。 表 8 IL-6、T淋巴细胞绝对值预测奥密克戎变异株老年重症感染者28 d预后ROC曲线

Table 8. The ROC curves of IL-6 and absolute T lymphocyte count in prediction of 28 d prognosis of Omicron variant infected elderly severe patients

变量 曲线下面积 95%CI IL-6 0.818 0.702~0.933 T淋巴细胞绝对值 0.796 0.656~0.936 联合预测 0.887 0.793~0.980 IL:白细胞介素。 -

[1] World Health Organization . WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard[EB/OL]. (2023-03-09)[2023-03-09]https://covid19.who.int./ [2] 中国疾病预防控制中心[EB/OL]. (2023-03-18)[2023-0326]https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/szkb_11803/jszl_13141/202303/t20230318_264368.html. [3] Yang X,Yu Y,Xu J,et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan,China: A single-centered,retrospective,observational study[J]. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine,Lancet Respir Med,2020,8(5):475-481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [4] Zhang J,Dong X,Liu G,et al. Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity,severity,and mortality[J]. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology,2023,64(1):90-107. [5] 彭丁,杨爽,李邦一,等. 老年重症及危重症新型冠状病毒感染患者预后的危险因素分析[J]. 中华老年多器官疾病杂志,2021,20(8):600-603. [6] Ke H,Chang M R,Marasco W A. Immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants[J]. Vaccines,2022,10(9):1545. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10091545 [7] Kumar S,Thambiraja T S,Karuppanan K,et al. Omicron and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2: A comparative computational study of spike protein[J]. Journal of Medical Virology,2022,94(4):1641-1649. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27526 [8] Aouissi H A. Algeria’s preparedness for Omicron variant and for the fourth wave of COVID-19[J]. Global Health & Medicine,2021,3(6):413-414. [9] 中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会. 新型冠状病毒感染诊疗方案(试行第十版)[J]. 中国合理用药探索,2023,20(1):1-11. [10] Assmann-Wischer U,Simon M M,Lehmann-Grube F. Mechanism of recovery from acute virus infection. III. Subclass of T lymphocytes mediating clearance of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus from the spleens of mice[J]. Medical Microbiology and Immunology,1985,174(5):249-256. doi: 10.1007/BF02124809 [11] 廖宝林,施海燕,刘艳霞,等. 新型冠状病毒感染患者早期外周血淋巴细胞亚群及细胞因子特征[J]. 中华实验和临床感染病杂志(电子版),2021,15(3):182-188. [12] Moss P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2[J]. Nature Immunology,2022,23(2):186-193. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01122-w [13] Chen G,Wu D,Guo W,et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation,2020,130(5):2620-2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244 [14] Zheng M,Gao Y,Wang G,et al. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients[J]. Cellular & Molecular Immunology,2020,17(5):533-535. [15] He S,Fang Y,Yang J,et al. Association between immunity and viral shedding duration in non-severe SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant-infected patients[J]. Frontiers in Public Health,2022,10:1032957. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1032957 [16] Chu H,Zhou J,Wong B H,et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus efficiently infects human primary T lymphocytes and activates the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways[J]. The Journal of Infectious Diseases,2016,213(6):904-914. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv380 [17] Ren X,Wen W,Fan X,et al. COVID-19 immune features revealed by a large-scale single-cell transcriptome atlas[J]. Cell,2021,184(7):1895-1913.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.053 [18] Delorey T M,Ziegler C G K,Heimberg G,et al. COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets[J]. Nature,2021,595(7865):107-113. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03570-8 [19] Shen X R,Geng R,Li Q,et al. ACE2-independent infection of T lymphocytes by SARS-CoV-2[J]. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy,2022,7(1):83. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00919-x [20] Mukherjee A G,Wanjari U R,Murali R,et al. Omicron variant infection and the associated immunological scenario[J]. Immunobiology,Elsevier,2022,227(3):152222. [21] Akkız H. The biological functions and clinical significance of SARS-CoV-2 variants of corcern[J]. Frontiers in Medicine,2022,9:849217. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.849217 [22] Nuutila J. The novel applications of the quantitative analysis of neutrophil cell surface FcgammaRI (CD64) to the diagnosis of infectious and inflammatory diseases[J]. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases,2010,23(3):268-274. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833939b0 [23] Dimoula A,Pradier O,Kassengera Z,et al. Serial determinations of neutrophil CD64 expression for the diagnosis and monitoring of sepsis in critically ill patients[J]. Clinical Infectious Diseases:An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America,2014,58(6):820-829. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit936 [24] Hoffmann J,Etati R,Brendel C,et al. The low expression of Fc-Gamma receptor III (CD16) and high expression of Fc-Gamma Receptor I (CD64) on neutrophil granulocytes mark severe COVID-19 pneumonia[J]. Diagnostics,2022,12(8):2010. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12082010 [25] Benlyamani I,Venet F,Coudereau R,et al. Monocyte HLA-DR measurement by flow cytometry in COVID-19 patients: An interim review[J]. Cytometry. Part A:The Journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology,2020,97(12):1217-1221. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.24249 [26] Venet F,Demaret J,Gossez M,et al. Myeloid cells in sepsis-acquired immunodeficiency[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences,2021,1499(1):3-17. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14333 [27] Galbraith N,Walker S,Carter J,et al. Past,present,and future of augmentation of monocyte function in the surgical patient[J]. Surgical Infections,2016,17(5):563-569. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.014 [28] 王强,杨德兴,周维钰,等. 基于循环和细胞免疫效应指标为基础的脓毒性休克患者预后风险因素分析[J]. 昆明医科大学学报,2023,44(7):78-87. [29] Li T,Lu H,Zhang W. Clinical observation and management of COVID-19 patients[J]. Emerging Microbes & Infections,2020,9(1):687-690. [30] 王宇航,蔡芸,梁蓓蓓,等. COVID-19细胞因子风暴的预警与治疗进展[J]. 中国新药杂志,2020,29(13):1514-1519. [31] Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A,Gödel P,Subklewe M,et al. Cytokine release syndrome[J]. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer,2018,6:56. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0343-9 [32] Cummings M J,Baldwin M R,Abrams D,et al. Epidemiology,clinical course,and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: A prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet (London,England),2020,395(10239):1763-1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2 [33] Chen R,Sang L,Jiang M,et al. Longitudinal hematologic and immunologic variations associated with the progression of COVID-19 patients in China[J]. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology,Elsevier,2020,146(1):89. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.003 [34] 樊菡,王莉,王晓,等. 老年新型冠状病毒感染患者的临床特征[J]. 中国老年学杂志,2021,41(7):1414-1417. [35] Uciechowski P,Dempke W C M. Interleukin-6: A masterplayer in the cytokine network[J]. Oncology,2020,98(3):131-137. doi: 10.1159/000505099 -

下载:

下载: