Application Effect of A New Modified 3D PSI in Total Knee Arthroplasty for Knee Osteoarthritis

-

摘要:

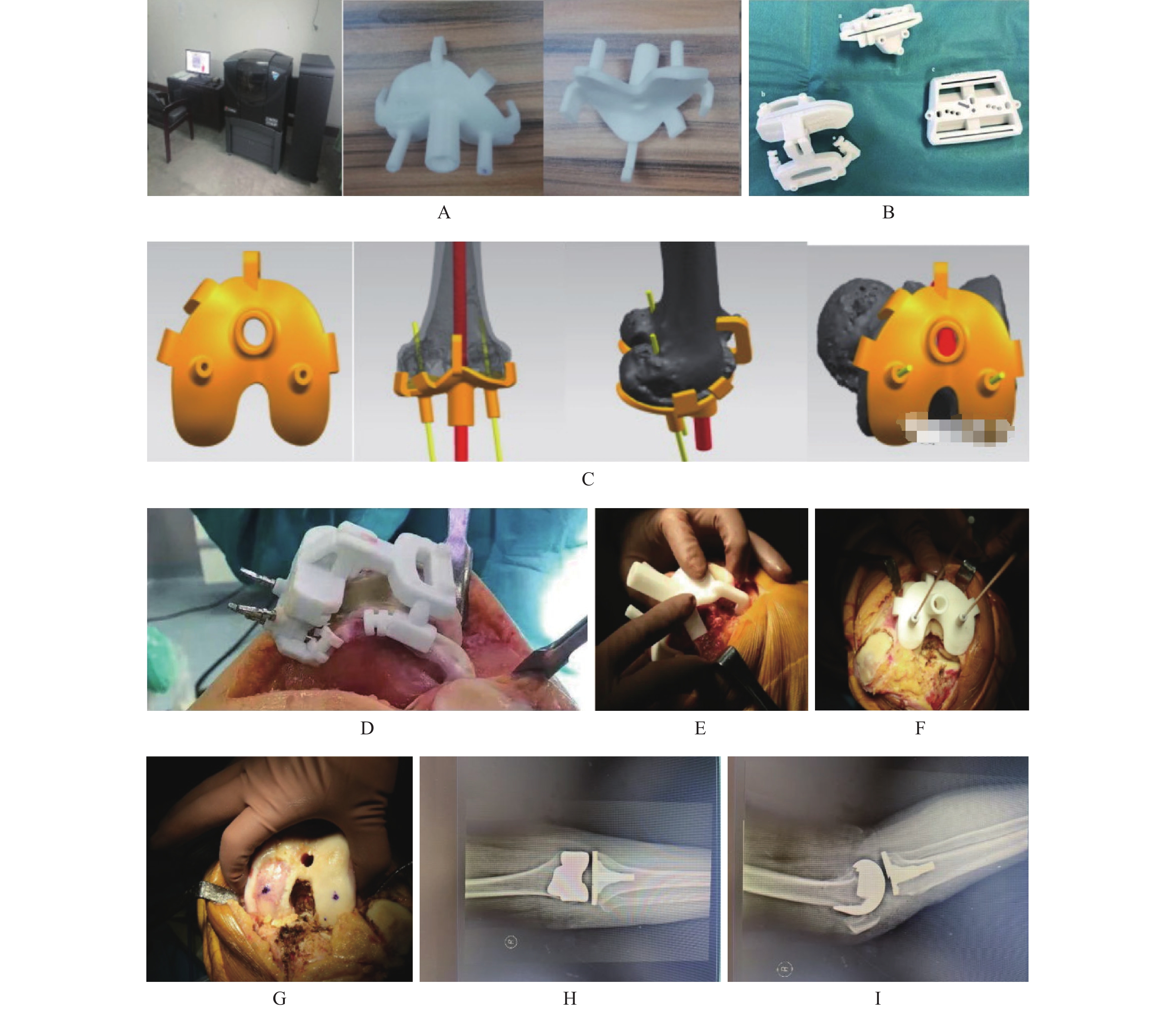

目的 探究膝关节骨性关节炎(knee osteoarthritis,KOA)全膝关节置换术(total knee arthroplasty,TKA)中新型改良3D打印个体化导向(patient specific in-strumentation,PSI)的应用效果。 方法 选取2021年1月至2022年1月解放军联勤保障部队九二〇医院100例KOA患者,采用随机数字表法分为2组,每组50例。对照组采用常规TKA治疗,研究组采用新型改良3D PSI辅助TKA治疗。观察患者手术情况、术后康复情况、并发症、假体组件位置偏差、膝关节活动度(range of motion,ROM)、下肢力线参数[冠状位股骨远端机械轴外侧角(mechanical lateral distal femoral angle,mLDFA)、下肢机械轴夹角(hip-knee-ankle,HKA)]、步态参数(支撑时间百分比、步幅、步速)、膝关节功能(hospital for special surgery,HSS评分)、生活质量(arthritis impact measurement scale 2,AIMS2评分)。 结果 研究组患者术中及术后出血量、术后2 d引流量较对照组少,手术时间、住院时间均较对照组短(P < 0.05);研究组患者LTC角、FFC角、HKA角、LFC角、FTC角偏差均较对照组小(P < 0.05);研究组患者术后3个月、6个月、12个月ROM、支撑时间百分比、步幅、步速均高于对照组,冠状位mLDFA、HKA低于对照组(P < 0.05);研究组患者术后3个月、6个月、12个月HSS评分高于对照组,AIMS2评分低于对照组(P < 0.05);研究组患者并发症发生率与对照组比较,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。 结论 新型改良3D PSI辅助TKA治疗KOA能优化手术情况,提高操作精度,改善患者下肢力线,促进肢体功能恢复,有助于提高生活质量,且具有较高安全性。 Abstract:Objective To explore the application effect of new improved 3D printing individualized guidance (3D psi) in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for knee osteoarthritis (KOA). Methods A total of 100 patients with KOA in 920th Hospital of Joint Logistics Support Force, PLA from January 2021 to January 2022 were selected, and were divided into 2 groups of 50 patients each using the randomized numerical table method. The control group was treated with conventional TKA, and the study group was treated with new improved 3D psi assisted TKA. The operation conditions, postoperative rehabilitation, complications, prosthesis component position deviation, knee range of motion (ROM), lower limb force line parameters [coronal distal femoral mechanical axis lateral angle (mldfa), lower limb mechanical axis angle (HKA)], gait parameters (percentage of support time, stride, pace), knee function(HSS score), quality of life (AIMS2 score) were observed. Results Compared with control group, the amount of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss and drainage volume 2 days after operation were less in the study group, and the operation time and hospital stay were shorter (P < 0.05). The deviations of LTC Angle, FFC Angle, HKA Angle, LFC Angle and FTC Angle in the study group were smaller than those in the control group (P < 0.05). At 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after surgery, the percentage of knee ROM, supporting time, stride length and walking speed of the research group were higher than those of the control group, while the coronal-position mLDFA and HKA were lower than those of the control group (P < 0.05). The proportion of WBC and PMN in joint fluid at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after surgery was lower than that in control group (P < 0.05). The HSS score of the study group was higher than that of the control group at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after operation, and the AIMS2 score was lower than that of the control group (P < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of complications between the study group and the control group (P > 0.05). Conclusion The new improved 3D PSI-assisted TKA treatment of KOA can optimize the surgical situation, improve operating accuracy, improve the patient’ s lower limb alignment, promote limb function recovery, help improve the quality of life, and has high safety. -

表 1 2组基线资料比较[($ \bar x \pm s$)/n(%)]

Table 1. Comparison of baseline data between two groups [($ \bar x \pm s$)/n(%)]

基线资料 研究组(n = 50) 对照组(n = 50) χ2/t P 性别 0.679 0.410 男 17(34.00) 21(42.00) 女 33(66.00) 29(58.00) 年龄(岁) 62.77 ± 6.72 64.15 ± 6.49 1.045 0.299 体重指数(kg/m2) 22.97 ± 1.46 23.21 ± 1.53 0.803 0.424 患肢 0.641 0.423 左侧 22(44.00) 26(52.00) 右侧 28(56.00) 24(48.00) 病程(a) 4.55 ± 0.72 4.74 ± 0.81 1.240 0.218 影像学K-L分级 1.010 0.315 Ⅲ级 20(40.00) 25(50.00) Ⅳ级 30(60.00) 25(50.00) 表 2 2组手术情况、术后康复情况比较 ($ \bar x \pm s$)

Table 2. Comparison of surgical conditions and postoperative rehabilitation between two groups ($ \bar x \pm s$)

组别 样本量(n) 术中及术后出血量(mL) 手术时间(min) 术后2 d引流量(mL) 住院时间(d) 研究组 50 364.85 ± 32.17 78.61 ± 6.39 267.65 ± 39.81 11.96 ± 2.65 对照组 50 425.63 ± 43.26 95.25 ± 8.11 329.14 ± 55.40 13.83 ± 3.40 t 7.972 11.396 6.374 3.067 P < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* 0.003* *P < 0.05。 表 3 2组假体组件位置偏差比较[($ \bar x \pm s$),°]

Table 3. Comparison of positional deviations between two groups of prosthetic components [($ \bar x \pm s$),°]

组别 样本量(n) LTC角 FFC角 HKA角 LFC角 FTC角 研究组 50 0.48 ± 0.15 0.29 ± 0.08 0.65 ± 0.19 3.81 ± 0.94 0.12 ± 0.03 对照组 50 0.79 ± 0.26 0.94 ± 0.26 1.86 ± 0.25 7.26 ± 1.52 0.86 ± 0.22 t 7.303 16.896 27.248 13.650 23.566 P < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* *P < 0.05。 表 4 2组膝关节ROM、下肢力线参数比较[($ \bar x \pm s$),°]

Table 4. Comparison of knee joint ROM and lower limb force line parameters between two groups [($ \bar x \pm s$),°]

指标 组别 样本量(n) 术前 术后3个月 术后6个月 术后12个月 合计 ROM 研究组 50 86.39 ± 4.22 108.71 ± 5.13 110.39 ± 5.04 110.75 ± 5.01 104.06 ± 5.03 对照组 50 87.54 ± 4.69 102.24 ± 4.87 103.51 ± 5.17 103.65 ± 5.21 99.24 ± 4.97 合计 100 86.97 ± 4.51 105.48 ± 4.96 106.95 ± 5.11 107.20 ± 5.14 101.65 ± 4.98 F 0.822 21.092 22.679 23.985 11.663 P 0.441 < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* 冠状位mLDFA 研究组 50 94.75 ± 9.64 85.13 ± 7.54 84.89 ± 7.61 84.76 ± 7.53 87.38 ± 8.01 对照组 50 94.13 ± 9.78 89.61 ± 8.20 89.45 ± 8.11 89.19 ± 8.06 90.60 ± 8.35 合计 100 94.44 ± 9.71 87.37 ± 7.86 87.17 ± 7.94 86.98 ± 7.82 88.99 ± 2.19 F 0.051 4.052 4.162 4.022 3.629 P 0.950 0.019* 0.017* 0.019* 0.028* HKA 研究组 50 7.63 ± 0.95 0.35 ± 0.11 0.33 ± 0.10 0.32 ± 0.10 2.16 ± 0.45 对照组 50 7.56 ± 0.91 0.84 ± 0.26 0.81 ± 0.25 0.80 ± 0.23 2.50 ± 0.52 合计 100 7.60 ± 0.93 0.60 ± 0.21 0.57 ± 0.22 0.56 ± 0.19 2.33 ± 0.48 F 0.072 71.497 67.995 85.240 6.191 P 0.931 < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* *P < 0.05。 表 5 2组步态参数比较($ \bar{x} \pm s$)

Table 5. Comparison of gait parameters between two groups ($ \bar x \pm s$)

指标 组别 样本量(n) 术前 术后3个月 术后6个月 术后12个月 合计 支撑时间百分比(%) 研究组 50 59.01 ± 1.24 62.87 ± 1.15 63.11 ± 1.20 63.25 ± 1.19 62.06 ± 1.19 对照组 50 59.33 ± 1.31 60.54 ± 1.22 61.03 ± 1.18 61.10 ± 1.21 60.50 ± 1.23 合计 100 59.17 ± 1.28 61.71 ± 1.20 62.07 ± 1.19 62.18 ± 1.20 61.28 ± 1.21 F 0.784 47.696 38.188 40.125 20.774 P 0.458 < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* 步幅(m) 研究组 50 1.02 ± 0.14 1.31 ± 0.12 1.33 ± 0.13 1.35 ± 0.12 1.25 ± 0.12 对照组 50 1.06 ± 0.15 1.19 ± 0.14 1.20 ± 0.12 1.21 ± 0.15 1.17 ± 0.14 合计 100 1.04 ± 0.14 1.25 ± 0.13 1.27 ± 0.12 1.28 ± 0.13 1.21 ± 0.13 F 0.984 10.620 14.104 13.864 4.720 P 0.376 < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* 0.01* 步速(m/s) 研究组 50 1.03 ± 0.12 1.31 ± 0.15 1.35 ± 0.16 1.36 ± 0.15 1.26 ± 0.14 对照组 50 1.06 ± 0.13 1.18 ± 0.13 1.20 ± 0.14 1.20 ± 0.16 1.16 ± 0.14 合计 100 1.05 ± 0.12 1.25 ± 0.14 1.28 ± 0.15 1.28 ± 0.15 1.21 ± 0.14 F 0.791 10.783 12.500 13.751 6.378 P 0.455 < 0.001* < 0.001* < 0.001* 0.002* *P < 0.05。 表 6 2组膝关节功能、生活质量比较[($ \bar{x} \pm s$),分]

Table 6. Comparison of knee joint function and quality of life between two groups [($ \bar x \pm s$) ,scores]

指标 组别 样本量(n) 术前 术后3个月 术后6个月 术后12个月 合计 HSS 研究组 50 46.13 ± 3.15 70.16 ± 3.67 78.21 ± 3.15 84.40 ± 2.86 69.48 ± 3.21 对照组 50 47.05 ± 3.22 68.23 ± 3.54 76.04 ± 3.22 82.15 ± 3.10 68.37 ± 3.05 合计 100 46.59 ± 3.18 68.70 ± 3.59 77.13 ± 3.20 83.28 ± 2.94 68.92 ± 3.12 F 1.045 4.070 5.775 7.217 1.577 P 0.354 0.019* 0.004* 0.001* 0.209 AIMS2 研究组 50 4.11 ± 0.76 2.75 ± 0.58 2.31 ± 0.44 2.26 ± 0.38 2.86 ± 0.51 对照组 50 4.02 ± 0.81 3.10 ± 0.62 2.65 ± 0.51 2.59 ± 0.42 3.04 ± 0.56 合计 100 4.07 ± 0.78 2.83 ± 0.60 2.48 ± 0.47 2.43 ± 0.40 2.95 ± 0.53 F 0.166 4.878 6.455 8.501 1.427 P 0.847 0.009* 0.002* < 0.001* 0.243 *P < 0.05。 表 7 2组并发症比较[n(%)]

Table 7. Comparison of complications between two groups [n(%)]

组别 样本量(n) 切口感染 关节肿胀 关节僵硬 皮下淤血 下肢DVT 合计 研究组 50 1(2.00) 0(0.00) 0(0.00) 1(2.00) 2(4.00) 4(8.00) 对照组 50 1(2.00) 2(4.00) 1(2.00) 2(4.00) 3(6.00) 9(18.00) χ2 2.210 P 0.137 -

[1] Sharma L. Osteoarthritis of the knee[J]. N Engl J Med,2021,384(1):51-59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1903768 [2] Brophy R H,Fillingham Y A. AAOS clinical practice guideline summary: Management of osteoarthritis of the knee (nonarthroplasty),third edition[J]. J Am Acad Orthop Surg,2022,30(9):e721-e729. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-01233 [3] Alrawashdeh W,Eschweiler J,Migliorini F,et al. Effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty rehabilitation programmes: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Rehabil Med,2021,53(6):jrm00200. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2827 [4] Cheng L,Ren P,Zheng Q,et al. Implication of changes in the imaging measurements after mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty[J]. Orthop Surg,2022,14(12):3322-3329. doi: 10.1111/os.13456 [5] 李凡,贺统,杨晶,等. SLA激光3D打印导向器在全膝关节置换术中的应用研究[J]. 中国数字医学,2018,13(2):5-9,12. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7571.2018.02.002 [6] Lipskas J,Deep K,Yao W. Robotic-Assisted 3D bio-printing for repairing bone and cartilage defects through a minimally invasive approach[J]. Sci Rep,2019,9(1):3746. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38972-2 [7] 杨滨,袁亮,张克,等. 新型改良3D打印个体化导向器辅助全膝关节置换术的精准度研究[J]. 中华骨科杂志,2021,41(2):67-75. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121113-20200715-00451 [8] Halonen J I,Erhola M,Furman E,et al. The helsinki declaration 2020: Europe that protects[J]. Lancet Planet Health,2020,4(11):e503-e505. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30242-4 [9] 中华医学会骨科学分会关节外科学组. 骨关节炎诊疗指南(2018年版)[J]. 中华骨科杂志,2018,38(12):705-715. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2352.2018.12.001 [10] Macri E M,Runhaar J,Damen J,et al. Kellgren/Lawrence grading in cohort studies: Methodological update and implications illustrated using data from a dutch hip and knee cohort[J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken),2022,74(7):1179-1187. doi: 10.1002/acr.24563 [11] Kahlenberg C A,Nwachukwu B U,Mehta N,et al. Development and validation of the hospital for special surgery anterior cruciate ligament postoperative satisfaction survey[J]. Arthroscopy,2020,36(7):1897-1903. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.02.043 [12] Sanal-Toprak C,Unal-Ulutatar Ç,Duruöz E,et al. The validity and reliability of the turkish version of the arthritis impact measurement scale 2-short form (AIMS2-SF) for rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Rheumatol Int,2023,43(4):751-756. [13] Lüring C,Beckmann J. Custom made total knee arthroplasty: review of current literature[J]. Orthopade,2020,49(5):382-389. doi: 10.1007/s00132-020-03900-0 [14] Solaini L,Bocchino A,Avanzolini A,et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic left colectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis,2022,37(7):1497-1507. doi: 10.1007/s00384-022-04194-8 [15] Al-Dulimi Z,Wallis M,Tan D K,et al. 3D printing technology as innovative solutions for biomedical applications[J]. Drug Discov Today,2021,26(2):360-383. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.11.013 [16] Keskinis A,Paraskevopoulos K,Diamantidis D E,et al. The role of 3d-printed patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty: A literature review[J]. Cureus,2023,15(8):e43321. [17] 孙彬,张继晓,袁亮,等. 改良3D打印个体化导向器辅助全膝关节置换术的假体型号与术前规划一致性分析[J]. 陆军军医大学学报,2022,44(15):1523-1530. [18] Nedopil A J,Howell S M,Hull M L. Deviations in femoral joint lines using calipered kinematically aligned TKA from virtually planned joint lines are small and do not affect clinical outcomes[J]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc,2020,28(10):3118-3127. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05776-w [19] Hua L,Lei P,Hu Y. Knee reconstruction using 3D-printed porous tantalum augment in the treatment of charcot joint[J]. Orthop Surg,2022,14(11):3125-3128. doi: 10.1111/os.13484 [20] Iannotti J P,Walker K,Rodriguez E,et al. Accuracy of 3-dimensional planning,implant templating,and patient-specific instrumentation in anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am,2019,101(5):446-457. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01614 [21] Ehlinger M,Favreau H,Murgier J,et al. Knee osteotomies: The time has come for 3d planning and patient-specific instrumentation[J]. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res,2023,109(4):103611. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2023.103611 -

下载:

下载: