An Economical Method for Cultivation and Identification of Mast Cell Derived from Suckling Rabbit Bone Marrow

-

摘要:

目的 通过一种操作简单的体外诱导培养体系获得更加成熟、更具有典型特征的肥大细胞。 方法 将乳兔的骨髓吹出放入含DMEM高糖培养基中,隔天换液,待细胞铺满,改用F12诱导培养基,隔天换液,镜下观察有细胞变圆时,更换为1640促成熟培养基,隔7 d换液,直至细胞诱导成熟。利用甲苯胺蓝染色检测其功能,流式细胞仪检测表面CD117及FcεR1α表达结果。 结果 6周后甲苯胺蓝染色可观察到:加入β-巯基乙醇的可得到含较多异染颗粒的细胞。采用流式细胞术进行检测:加入β-巯基乙醇时:CD117+、FcεRIα+双阳性细胞的比例为 96.2%,与不加β-巯基乙醇相比有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。 结论 利用SCF、IL-3及β-巯基乙醇可以成功诱导出兔骨髓来源的肥大细胞,为下一步对兔进行炎性损伤研究提供了依据,使后续基础及临床研究成为可能。 Abstract:Objective To obtain more mature mast cells with more typical characteristics through a simple and well-operated in vitro induction culture system. Methods The bone marrow of suckling rabbits was blown out and put into high glucose medium containing DMEM, and the medium was changed every other day. When the cells were confluent, F12 induction medium was used, and the medium was changed every other day. When the cells became round under the microscope, 1640 maturation medium was replaced, and the medium was changed every 7 days until the cells were induced to mature. Toluidine blue staining was used to detect its function, and flow cytometry was used to detect the surface expression of CD117 and FcεR1α. Results After 6 weeks, toluidine blue staining showed that the cells containing more metachromatic particles could be obtained by adding β-mercaptoethanol. Flow cytometry showed that the proportion of CD117+ and FcεRIα+ double positive cells in the presence of β-mercapto ethanol was 96.2%, which was significantly higher than that in the absence of β-mercapto ethanol (P < 0.05). Conclusion The use of SCF, IL-3 and β-mercaptoethanol can successfully induce mast cells derived from rabbit bone marrow, which provides foundation for the future research on inflammatory injury in rabbits, and makes subsequent basic and clinical research possible. -

Key words:

- Suckling rabbit /

- Bone marrow /

- Mast cells /

- Induction

-

九十年代初期的研究表明,在动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis,AS)形成过程中,动脉内膜和外膜层聚集着肥大细胞(mast cells,MCs),首次提出MCs参与AS进程[1]。

血管的微环境一旦发生变化,炎性细胞便会从血管外膜的滋养血管中渗出,参与疾病的变化[2-3]。MCs激活时释放出来的趋化因子、细胞因子、组胺、白三烯等炎症因子[4]使血管的通透性增加,导致单核巨噬细胞和淋巴细胞聚集到斑块处[5],释放出大量的中性蛋白酶,可以加速低密度脂蛋白(low-density lipoprotein,LDL)进入到血管内膜局部并聚集[6],促进AS斑块形成。

在骨髓细胞向MCs分化及活化过程中白细胞介素3(interleukin-3,IL-3)和干细胞因子(stem cell factor,SCF)起到重要作用[7-8]。本研究旨在通过提取乳兔骨髓细胞,利用IL-3、SCF、β-巯基乙醇联合作用诱导培养骨髓来源肥大细胞并鉴定其纯度与活性,为进一步研究肥大细胞与AS的关系提供依据。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 材料

IL-3、SCF(美国Peprotech公司);FBS、DMEM、DMEM/F12、RPMI-1640(美国Gibco公司);实验动物:2周龄乳兔,昆明医科大学实验动物学部,环境条件符合国家实验动物环境及设施标准要求,室内保持安静、清洁、干燥和通风。自由饮水。实验动物使用许可证号:SCXK(滇)2015-0002。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 兔骨髓细胞的获取

麻醉:(经2周龄乳兔耳缘静脉注射3%戊巴比妥钠,1 mL/kg)→浸泡(75%C2H5OH,10 min)→剥离(后肢皮肤切开,逐层分离,剥离肌肉)→暴露股骨→取出→浸泡(75% C2H5OH的无菌培养皿中浸泡3~5 min)→股骨两端剪去→吹打骨髓(吸取DMEM高糖培养基后吹打骨髓,股骨变白)→获取细胞(1000 r/min,5 min。如果在获取的细胞中有较多红细胞,则应用红细胞裂解液进行处理)→培养体系(含84 mL DMEM高糖培养基、15 mL FBS、1 mL双抗)。

1.2.2 细胞的培养

接种到T25瓶中(含DMEM高糖培养基)→隔天换液→细胞铺满→消化细胞→新培养瓶→贴壁→改用F12诱导培养基(含84 mL DMEM/F12、15 mL FBS、1 mL双抗、10 ng/mL SCF、10 ng/mL IL-3及0、10×10-5 mol/L的β-巯基乙醇)→放置37 ℃、5% CO2 饱和湿度环境→隔天换液→镜下观察细胞有变圆→更换为1640促成熟培养基(含84 mL RPMI 1640、15 mFBS、1 mL双抗、10 ng/mL SCF、10 ng/mL IL-3及0、10×10-5 mol/L的β-巯基乙醇)→7 d换液→直至细胞诱导成熟。

1.2.3 肥大细胞功能学鉴定

诱导成熟的重悬细胞液→载玻片→干燥→甲苯胺蓝染色→95% C2H5OH脱色→清洗→镜下观察。

1.2.4 肥大细胞形态学鉴定

通过光镜下观察不同培养时间的细胞形态,直至诱导成熟。

消化细胞→洗2次(PBS)→细胞密度1×10 7个/mL→每管100 μL→单染管各加入5.0 μL的 CD117-PE抗体及FcεR1α-FITC抗体→双染管加两种抗体→空白对照管(无抗体)→避光孵育30 min→每管加1 mL PBS→离心10 min(400 g)→去上清→上法洗涤1次→去上清→每管加100 μL PBS→检测。

2. 结果

2.1 光镜下观察肥大细胞生长形态

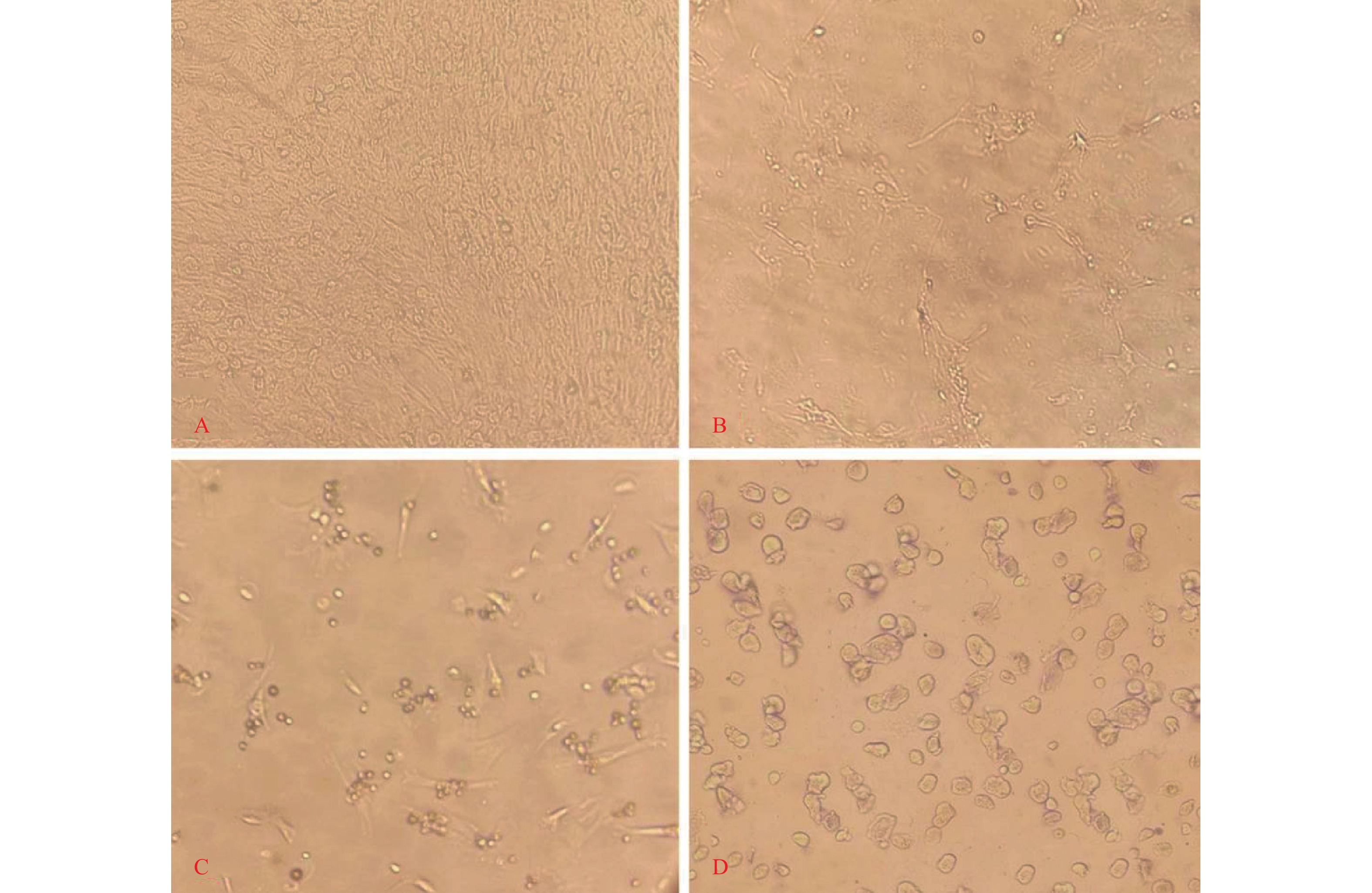

2 d后开始出现以形态为长梭形的贴壁细胞;7 d时:细胞基本将培养瓶铺满;2周时:细胞逐渐变形;4周时:细胞基本变为圆形,悬浮细胞变多;6周时:细胞基本变为类圆形,且形态均匀具有折光性(图1)。

2.2 肥大细胞的甲苯胺蓝染色

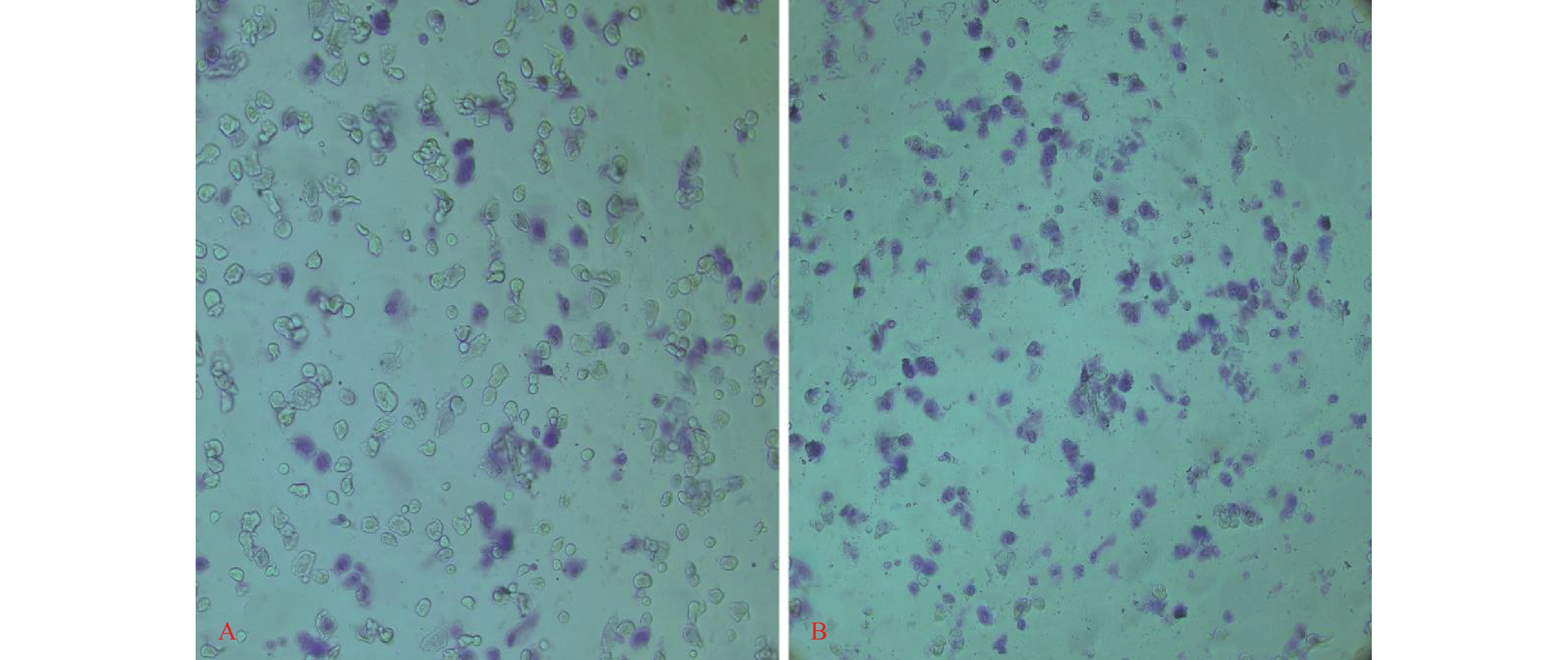

培养6周细胞成熟后利用甲苯胺蓝染色:可以观察到细胞质为紫红色,细胞核为蓝色。异染颗粒的细胞加入β-巯基乙醇比不加入β-巯基乙醇的能得到更多(图2)。

2.3 流式细胞术检测肥大细胞

培养6周收集细胞,利用流式细胞术检测细胞表面CD117及FcεR1α的表达情况,加入β-巯基乙醇双阳性细胞的比例达96.2%,大于不加入β-巯基乙醇的(图3),且与不加β-巯基乙醇相比有统计学意义(P < 0.05),见表1。

表 1 不同浓度β-巯基乙醇诱导后CD117+ FcεRIα+肥大细胞的比例Table 1. The proportion of CD117+ FcεRIα+ mast cells induced by different concentrations of β-mercaptoethanolβ-巯基乙醇

(mol/L)实验次数 CD117+ FcεRIα+

肥大细胞的比例(%)P 0 5 48.97 ± 3.12 0.7069 10×10−5 5 95.64 ± 4.66# 与β-巯基乙醇浓度为0 mol/L比较,#P < 0.05。 3. 讨论

在正常人的心脏、主动脉及脂肪组织中有少量的MCs存在,当人类发生疾病时MCs的数量就会增多,比如AS。近年来,研究表明MCs在AS的发生、发展及斑块稳定性中有着重要作用[9]。

当下有研究认为MCs是利用其表面的趋化因子受体-3与AS斑块中表达的嗜酸细胞活化CC趋化因子亚族中趋化因子配体-11结合而向病变部位聚集[10]。MCs起源于骨髓造血干细胞[11],促进MCs成熟的分子主要有SCF和神经生长因子(nerve growthfactor,NGF)[17],SCF可能在MCs向受累区域聚集发挥作用,而MCs侵入受累区域可能会进一步导致更多的炎性细胞浸润,促进AS斑块形成。

IL-3又被叫做肥大细胞生长因子,在MCs的生长、分化、迁移和效应中具有重要作用。活化T细胞、天然杀伤(NK)细胞和MCs都可产生IL-3,且对于SCF在MCs前体的发生、发展、扩增具有促进意义[12-13]。SCF的配体CD117(c-kit)除在其表面外,各种造血祖细胞中均可存在。MCs发挥重要表面标志的是FcεRIα,但FcεRIα还表达于嗜酸性粒细胞等细胞表面,只有MCs同时表达CD117和FcεRIα[14]。甲苯胺蓝染色是一种常用于识别及判断MCs功能状态的方法,同时也是MCs的特异性染色,可染细胞核为蓝色,胞质内为异染性紫红色颗粒,说明其具有吞噬功能[15]。通过甲苯胺蓝染色和流式细胞仪检测结果对诱导获得的MCs的纯度进行鉴定,就目前来说,利用兔的骨髓间质干细胞来诱导培养MCs的报道是极少的。

本研究选用2周龄的乳兔来获取骨髓间质干细胞,因为当兔龄大于或者小于2周龄时,笔者发现细胞生长速度变得缓慢,可能是2周龄的骨髓间质干细胞的活性更好,更有利于细胞的培养。当IL-3浓度10 ng/mL、SCF浓度为10 ng/mL,加入β-巯基乙醇时:甲苯胺蓝染色及流式检测均较不加入β-巯基乙醇时可以获取更多、双阳性率更高的MSc,原因可能为β-巯基乙醇作为一种还原剂,在降低氧对细胞产生氧化损伤的同时促进干细胞生长。所以该培养体系是一种良好的体外诱导培养体系,其操作简单,且能获得更加成熟、更具有典型特征的MCs,为下一步对兔行进炎性损伤研究提供了优势。综上所述,本研究利用形态学、功能学2个方面对诱导的兔骨髓来源MCs进行鉴定,培养出的细胞不仅具有成熟MCs的生物学特性,还具有其功能,这便为后续的基础研究及临床研究奠定基础。

-

表 1 不同浓度β-巯基乙醇诱导后CD117+ FcεRIα+肥大细胞的比例

Table 1. The proportion of CD117+ FcεRIα+ mast cells induced by different concentrations of β-mercaptoethanol

β-巯基乙醇

(mol/L)实验次数 CD117+ FcεRIα+

肥大细胞的比例(%)P 0 5 48.97 ± 3.12 0.7069 10×10−5 5 95.64 ± 4.66# 与β-巯基乙醇浓度为0 mol/L比较,#P < 0.05。 -

[1] Kaartinen M,Penttilä A,Kovanen P T. Accumulation of activated mast cells in the shoulder region of human coronary atheroma,the predilection site of atheromatous rupture[J]. Circulation,1994,90(4):1669-1678. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.4.1669 [2] Spinas E,Kritas S K,Saggini A,et al. Role of mast cells in atherosclerosis: a classical inflammatory disease[J]. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol,2014,27(4):517-521. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700407 [3] Sun W,Pang Y,Liu Z,et al. Macrophage inflammasome mediates hyperhomocysteinemia-aggravated abdominal aortic aneurysm[J]. J Mol Cell Cardiol,2015,81:96-106. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.02.005 [4] Kovanen P T,Bot I. Mast cells in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease-Activators and actions[J]. Eur J Pharmacol,2017,816:37-46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.10.013 [5] Conti P,Lessiani G,Kritas S K,et al. Mast cells emerge as mediators of atherosclerosis: special emphasis on IL-37 inhibition[J]. Tissue Cell,2017,49(3):393-400. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2017.04.002 [6] Maaninka K,Nguyen S D,Mäyränpää M I,et al. Human mast cell neutral proteases generate modified LDL particles with increased proteoglycan binding[J]. Atherosclerosis,2018,275:390-399. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.04.016 [7] Oliveira S H,Lukacs N W. Stem cell factor: a hemopoietic cytokine with important targets in asthma[J]. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy,2003,2(4):313-318. [8] Irani A M,Nilsson G,Miettinen U,et al. Recombinant human stem cell factor stimulates differentiation of mast cells from dispersed human fetal liver cells[J]. Blood,1992,80(12):3009-3021. [9] Kaartinen M,Penttilä A,Kovanen P T. Mast cells of two types differing in neutral protease composition in the human aortic intima. Demonstration of tryptase- and tryptase/Chymase -containing mast cells in normal intimas,fatty streaks,and the shoulder region of atheromas[J]. Arterioscler Thromb,1994,14(6):966-972. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.14.6.966 [10] Bot I,Shi G P,Kovanen P T. Mast cells as effectors in atherosclerosis[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol,2015,35(2):265-271. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303570 [11] Ribatti D. The development of human mast cells. an historical reappraisal[J]. Exp Cell Res,2016,342(2):210-215. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.03.013 [12] Kritas S K,Saggini A,Cerulli G,et al. Interrelationship between IL-3 and mast cells[J]. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents,2014,28(1):17-21. [13] Ito T,Smrž D,Jung M Y,et al. Stem cell factor programs the mast cell activation phenotype[J]. J Immunol,2012,188(11):5428-5437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103366 [14] Meurer S K,Neß M,Weiskirchen S,et al. Isolation of mature (peritoneum-derived) mast cells and immature (bone marrow-derived) mast cell precursors from mice[J]. PLoS One,2016,11(6):e0158104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158104 [15] Sayed S O,Dyson M. Histochemical heterogeneity of mast cells in rat dermis[J]. Biotech Histochem,1993,68(6):326-32. doi: 10.3109/10520299309105638 -

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: