Epidemiological Situation of Parasitic Diseases in South and Southeast Asian Countries along the “One Belt and One Road”

-

摘要: “一带一路”共建国家的八个南亚国家和十一个东南亚国家是寄生虫病的高发区。由于受地理位置、经济状况、文化背景、饮食习惯等诸多原因的影响,疟疾、利士曼原虫、刚地弓形虫、蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫、人芽囊原虫、溶组织内阿米巴、阴道毛滴虫、日本血吸虫、蛔虫、鞭虫、钩虫、粪类圆线虫、蛲虫、带绦虫和丝虫等多种人体寄生虫在该地区流行严重,是一个严峻的公共卫生问题。分析和认识“一带一路”共建国家南亚和东南亚国家寄生虫病的流行状况,有的放矢地制定防控措施,对预防跨境传染病的发生、促进各国之间的密切合作及彻底消除寄生虫病有重要的意义。Abstract: Eight South Asian countries and eleven Southeast Asian countries along the "One Belt and One Road" are areas with high incidences of parasitic diseases. Due to the influence of geographical location, economic status, cultural background, and dietary habits, several human parasites such as Plasmodium spp, Leishmania spp, Toxoplasma gondii, Giardia lamblia, Blastocystis hominis, Entamoeba histolytica, Trichomonas vaginalis, schistosoma japonicum, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichiruss trichiura, hookworm, strongyloides stercoralis, Enterobius vermicularis, tapeworms, and filaria are prevalent. Parasitic diseases are a serious public health problem in these regions. Analyzing the epidemic situation of parasitic diseases in South and Southeast Asian countries along the "One Belt and One Road", and formulating targeted measures of prevention and control are helpful for preventing the occurrence of cross-border infectious diseases, promoting close cooperation between countries, and completely eliminating parasitic diseases.

-

Key words:

- One Belt and One Road /

- Parasitic diseases /

- South Asia /

- Southeast Asia

-

根据国际糖尿病联盟的分析,预计到2045年,糖尿病患者的数量将从2030年的5.78亿增加到7.00亿人,这意味着世界各地的公共卫生威胁日益增加[1]。其中2型糖尿病(type 2 diabetes mellitus,T2DM)约占全球所有糖尿病患者的90%, 是一种受遗传和环境风险综合影响的复杂疾病,越来越多的研究表明微生物失调在T2DM 发病机制中的作用[2]。前期研究发现:恒古骨伤愈合剂具有降血糖功效,可改善2型糖尿病db/db小鼠肠道微生态平衡[3]。广谱抗生素引起宿主肠道菌群失调。因此,本实验进一步探索恒古骨伤愈合剂联合广谱抗生素对糖尿病小鼠的作用,为进一步的药物开发提供理论依据。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 实验动物

SPF级10周龄雄性 db/db小鼠和野生型小鼠,购于北京斯贝福公司[SCXK(京)2019-0010],在昆明医科大学[许可证SYXK(滇)2020-0006]饲养:室温(23±2)℃,湿度(52±10)%,明暗交替时间为12 h。小鼠自由采食和饮水。相关操作遵守动物福利要求,试验方案通过伦理委员会批准(KMMU20220903)。

1.2 药物和仪器

恒古骨伤愈合剂(批号:20211211)来自克雷斯制药公司。抗生素(万古霉素,氨苄西林,甲硝唑,新霉素)来自美国Sigma公司。小鼠胰岛素酶联免疫吸附测定试剂盒购自齐一生物科技(上海)公司。血糖检测仪为三诺生物公司制造。

1.3 实验方法

1.3.1 分组与样本采集

适应性饲养2 w后,野生型小鼠为对照组(wt),24只db/db小鼠随机分为模型组(db组)、恒古骨伤愈合剂组(OK组)、广谱抗生素组(ABX组)、恒古骨伤愈合剂与抗生素联合干预组(AO组)(n = 6)。OK组以临床成人常用剂量(按60 kg计算),并按人和动物体表面积换算法折算等效剂量为15.3 g/(kg.2 d),ABX组灌胃等体积广谱抗生素(甲硝唑1 g/L、氨苄西林1 g/L、0.5 g/L 万古霉素和1 g/L新霉素)、对照组、模型组灌胃等体积0.9 %氯化钠溶液,每2 d给药1次。AO组给与恒古骨伤愈合剂与抗生素交替灌胃,共11周。禁食 12 h,测量小鼠体重、空腹血糖,3% 戊巴比妥钠麻醉,采心脏血离心,收集血清检测胰岛素,计算胰岛素抵抗指数(HOMA-IR)。公示为HOMA-IR = 空腹血糖 (mmol/L)× 空腹胰岛素(μU/mL )/ 22.5(校正因子)。取盲结肠内容物0.5 g~1.0 g,分装至无菌 EP 管,过液氮,-80 ℃保存。

1.3.2 肠道菌群16S rDNA测序

由上海百趣公司利用Illumina NovaSeq测序平台测序进行。具体使用Hipure Stool DNA Kits 提取DNA,对16S rDNA V3 + V4区扩增,用AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit纯化PCR产物,ABI StepOnePlus System定量。原始数据提交SRA数据库,获得ASVs[4],物种注释。并进行菌群多样性分析、差异分析及功能预测。

1.4 统计学处理

采用SPSS 22.0分析数据,计量数据用平均数±标准差表示,组间比较采用单因素方差分析(方差齐) 或秩和检验(方差不齐),多重比较用LSD法或Nemenyi法,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 广谱抗生素、恒古骨伤愈合剂单独和联合使用改善db/db小鼠胰岛素抵抗

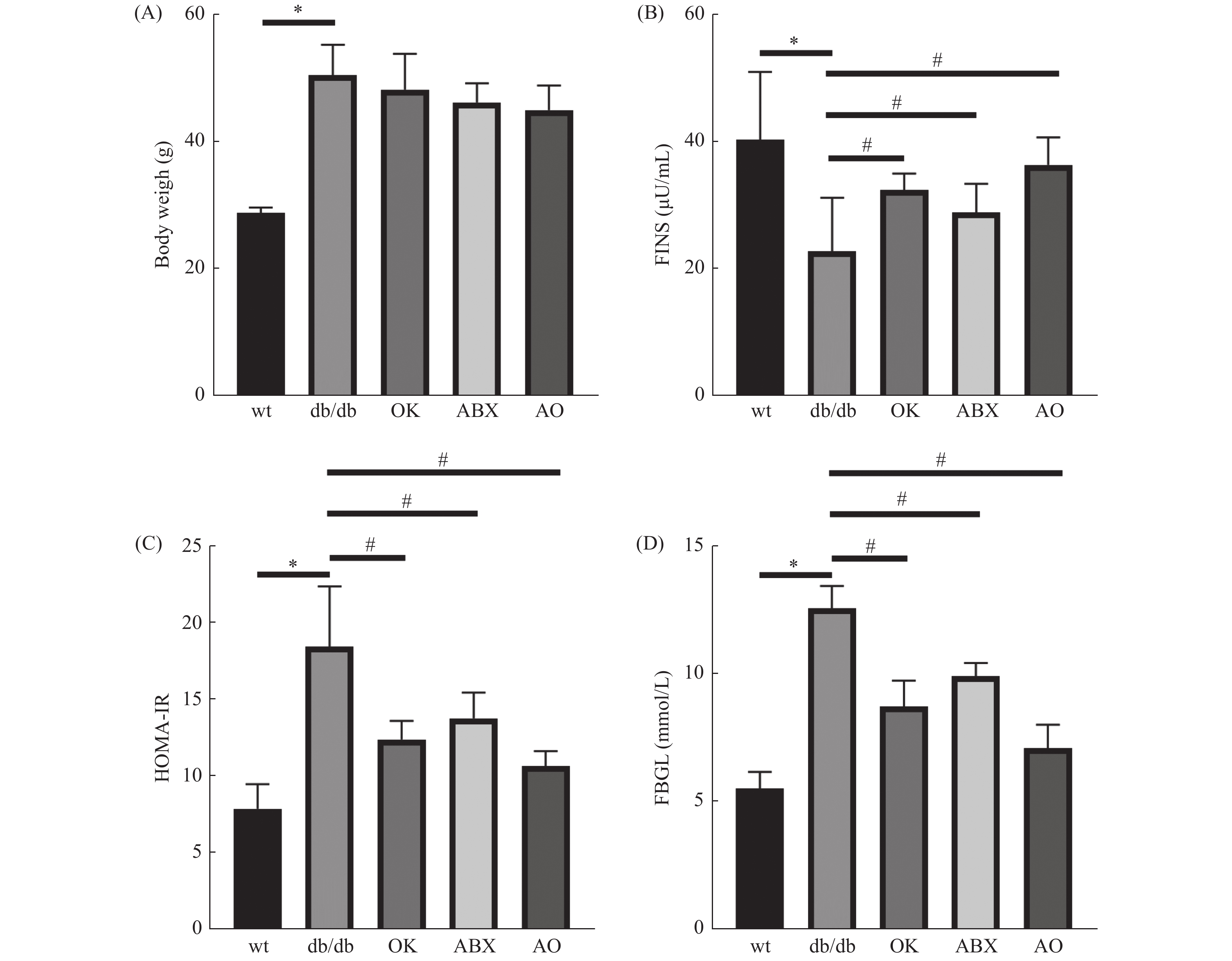

与野生型比较,db/db 小鼠体重(图1A)、空腹血糖(图1B)和胰岛素抵抗指数(图1C)升高,血清胰岛素(图1D)含量降低,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),提示db/db 小鼠出现T2DM的病理症状。与模型组(db/db )比较,广谱抗生素组、恒古骨伤愈合剂组和联合用药组空腹血糖和胰岛素抵抗指数降低,血清胰岛素含量升高,差异具有统计学意义( P < 0.05),但各处理组体重与模型组差异无统计学意义( P > 0.05)( 图1A)。

2.2 肠道菌群测序ASVs和韦恩图

5组小鼠韦恩图呈现小鼠间共有、特有的ASVs,其中对照组

1283 个ASVs;ABX、db/db、OK、AO组的ASVs依次增加(824个、878个、946个、1 330个),ABX组肠道菌群ASVs最少而AO组最多。提示抗生素抑制肠道菌群,恒古骨伤愈合剂改善这种抑制作用。2.3 肠道菌群丰富度和均匀性

与对照组wt小鼠比较,db/db组肠道菌群丰富度和均匀性相关指标chao1、shannon、simpson和pielou-e指数降低(P < 0.05)。与db/db组比较,OK组菌群丰富度和均匀性增加( P < 0.05);ABX组菌群丰富度和均匀性最低,差异具有统计学意义( P < 0.01);AO组菌群丰富度和均匀性介于db/db与ABX组之间,其中chao1和simpson指数与db/db组无统计学差异( P > 0.05)。提示恒古骨伤愈合剂改善抗生素作用下的db/db菌群的丰富度和均匀性。各组样本覆盖度大于99.7%,提示样本中的物种均被检测到( 表1)。

表 1 各组小鼠肠道菌群丰富度和均匀性指数( $ \bar x \pm s $)Table 1. Alpha-diversity index of gut microbiota in the 5 groups ( $ \bar x \pm s $)组别 chao1指数 shannon指数 simpson指数 Pielou-e指数 样本覆盖度 对照组(wt) 557.81 ± 78.59 7.16 ± 0.47 0.98 ± 0.0044 0.79 ± 0.039 1.00 模型组(db/db) 363.52 ± 28.91* 5.87 ± 0.64* 0.92 ± 0.0087 *0.69 ± 0.047* 1.00 广谱抗生素组(ABX) 193.04 ± 32.41## 3.70 ± 0.14## 0.84 ± 0.0091 ##0.49 ± 0.018## 1.00 恒古骨伤愈合剂组(OK) 467.39 ± 51.07# 6.84 ± 0.82# 0.96 ± 0.041# 0.78 ± 0.080# 1.00 联合用药组(AO) 311.28 ± 33.87 4.50 ± 0.50# 0.91 ± 0.013 0.59 ± 0.032# 1.00 F 4.01 15.75 13.41 11.69 — P 0.0132 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 — 与对照组比较,*P < 0.05;与模型组比较, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01。 2.4 门与科水平的肠道菌群丰度

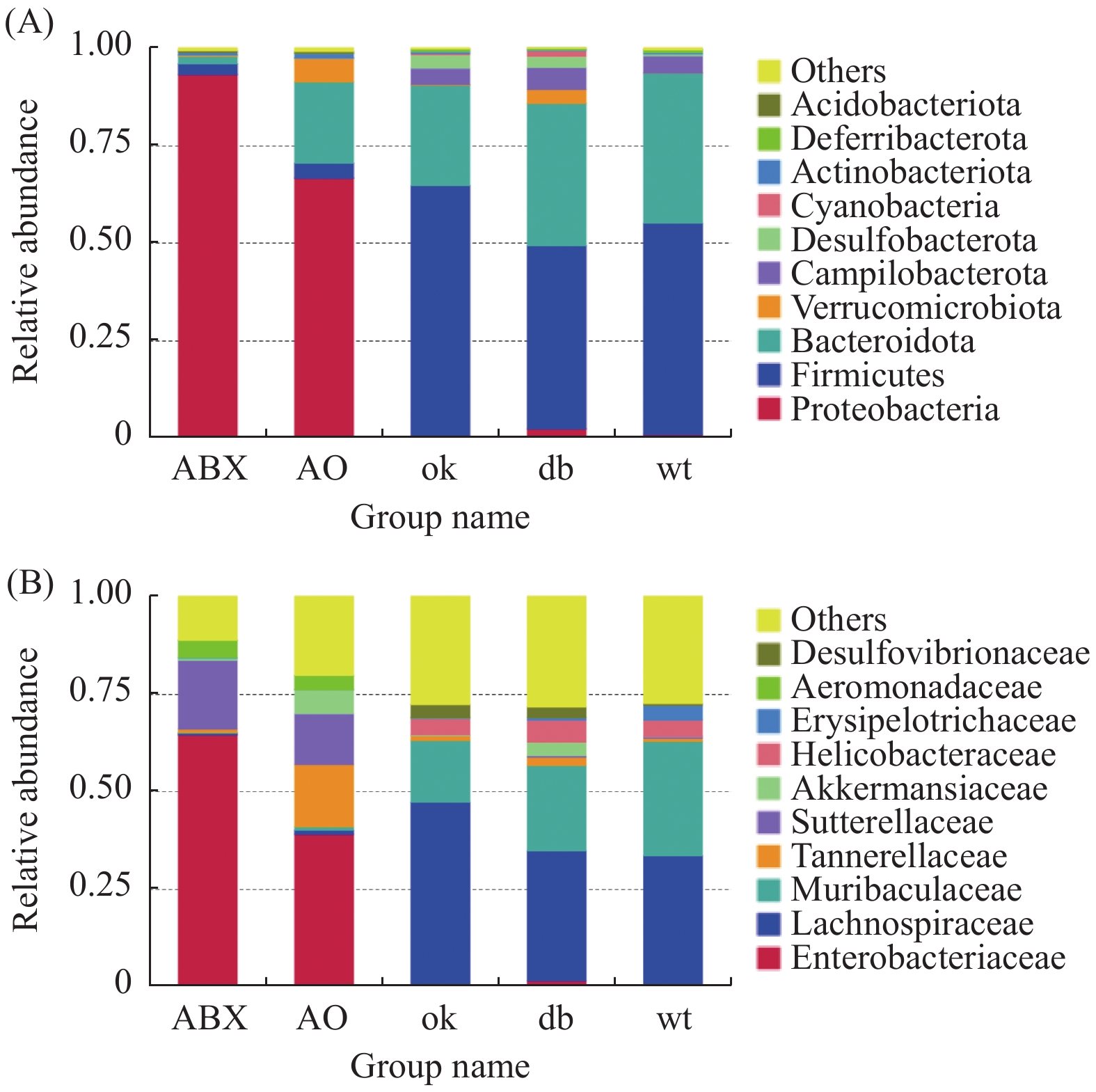

门水平上(图2A),db/db 和OK组厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)(0.471,0.644)和拟杆菌门(Bacteroidota)相对丰度最高(0.366,0.259)。ABX组变形菌门(Proteobacteria)的相对丰度高达0.934,AO组变形菌门相对丰度为0.667,其次为拟杆菌门(0.209)。进一步分析发现各组小鼠肠道菌门构成有明显差异,相对与db/db 组,OK组厚壁菌门(P < 0.05)、ABX( P < 0.01)和AO组( P < 0.01)变形菌门的丰度升高,OK组( P < 0.05)、AO组( P < 0.01)和ABX( P < 0.01)的拟杆菌门相对丰度降低。

科层面(图2B),db/db 小鼠和OK组毛螺菌科(Lachnospiraceae)(0.333、0.472)和Muribaculaceae科(0.219、0.159)群丰度最高。ABX组肠杆菌科(Enterobacteriaceae)和萨特菌科(Sutterellaceae)(0.650,0.178)丰度最高,AO组肠杆菌科、坦纳菌科(Tannerellaceae)和萨特菌科(0.390、0.162、0.130)丰度最高。5组小鼠肠道菌科构成差异明显,与db/db 组比较,OK组毛螺菌科(P < 0.05)、ABX和AO组肠杆菌科、萨特菌科及AO组坦纳菌科的丰度均升高( P < 0.01),而OK组Muribaculaceae丰度降低( P < 0.05)。

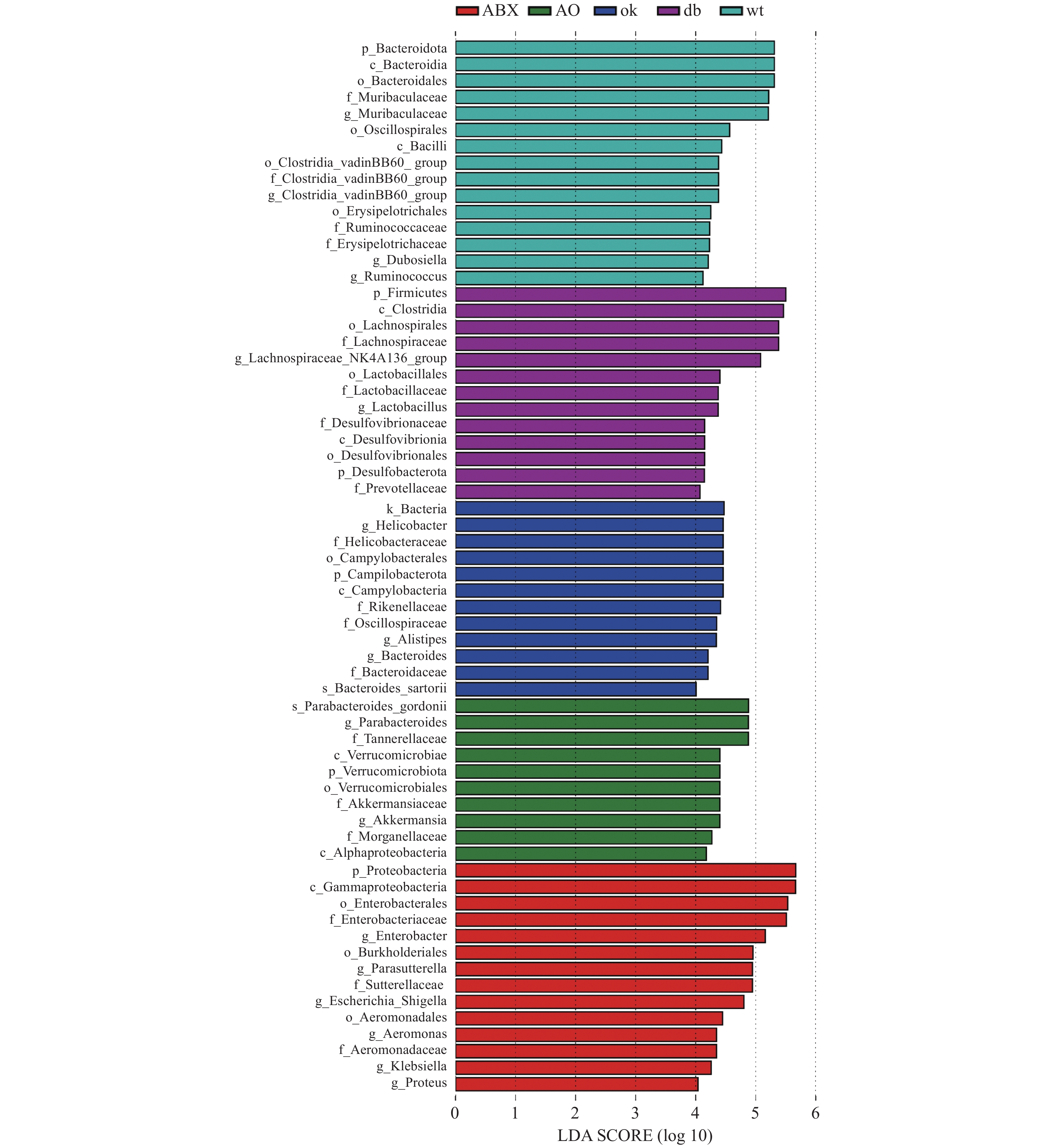

2.5 差异菌属筛

LEFse分析组间菌群差异(图3),野生型小鼠肠道菌群的优势物种为拟杆菌门Muribaculaceae属和厚壁菌门瓦丁梭菌BB60群(VadinBB60-group)、杜氏乳杆菌(Dubosiella)、瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus)。db/db小鼠的优势菌属为弯曲杆菌门螺旋杆菌属(Helicobacter)和拟杆菌门另枝菌属(Alistipes)和拟杆菌属(Bacteroides)。OK组的优势菌种为厚壁菌门毛螺菌科NK4A136组(Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group)和乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus),脱硫杆菌门(Desulfobacterota)脱硫杆菌科(Desulfobacteraceae) )和拟杆菌门的普雷沃氏菌科(Prevotellaceae)等。ABX组的优势菌均为变形菌门,包括γ-变形菌纲肠杆菌科(Enterobacteriaceae)、气单胞菌科(Aeromonadaceae)和β-变形菌纲的萨特氏菌科(Sutterellaceae)等。AO组肠道菌群的优势物种包括古氏副拟杆菌(Parabacteroides gordonii),疣微菌门阿克曼菌属(Akkermansia)和变形菌门γ-变形菌纲肠杆菌目的摩根菌科(Morganellaceae)及α-变形菌纲(Alphaproteobacteria)等。 3. 讨论

糖尿病在中医学中属于“消渴病”范畴,由于先天不足、劳倦内伤、饮食失节、情志失调等导致。中医药治疗糖尿病已千余年,在“天人合一”的整体观念指导下,注重对患者全身功能的调节[5]。彝药恒古骨伤愈合剂由陈皮、红花、三七、杜仲、人参、黄芪、洋金花、钻地风、鳖甲等配方制成,功能主治为活血益气、补肝肾,符合中药治疗糖尿病的原则。课题前期发现恒古骨伤愈合剂改善db/db小鼠糖尿病性骨代谢异常和降低空腹血糖[3]。由于胰岛素在糖脂代谢中发挥重要作用,胰岛素抵抗指数(homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance,HOMA-IR)是判断胰岛素抵抗的有效指标[6],本实验进一步发现恒古骨伤愈合剂改善db/db小鼠胰岛素抵抗。

肠道菌通过微生物-宿主共代谢系统影响药物代谢。通过抗生素处理杀灭微生物是研究肠道菌群变化的替代方法。抗生素可通过种类、剂量、给药途径及时间的不同,影响肠道菌群组成和结构[7]。抗生素诱导的肠道群的改变与代谢性疾病相关,如肥胖、糖尿病等[4]。选择广谱抑菌且肠道内吸收率相对缓慢的抗生素,其中包括万古霉素、氨苄西林、甲硝唑、新霉素的组合,已被证明对肠道菌群有杀伤作用[8]。本实验选择了以上混合抗生素,通过比对抗生素、恒古骨伤愈合剂单独和联合作用于db/db小鼠的效应。结果显示:经11周干预,抗生素、恒古骨伤愈合剂单独和联合作用,均降低2型糖尿病db/db小鼠空腹血糖和胰岛素抵抗,联合用药组效果更优。与本实验结果类似,出生至成年的长期抗生素暴露,通过调节肠道菌群在一定程度上抵抗高脂饮食负荷小鼠的糖代谢失调[9]。万古霉素降低NOD小鼠的糖尿病发病率[10]。广谱抗生素(给药12 d)降低db/db小鼠随机血糖,改变肠道微生物群组成[11]。本实验也表明广谱抗生素降低 db/db小鼠肠道菌群的丰富度与均匀性。广谱抗生素主要通过抑制拟杆菌门等常见的共生专性厌氧菌,并扩大正常情况下丰度较低变形杆菌门等兼性厌氧菌重塑肠道微生态[12-13]。相似地,本实验也发现ABX和AO组拟杆菌门相对丰度降低,变形菌门的丰度升高。而恒古骨伤愈合剂改善抗生素作用下的菌群的多样性。

LEFse分析显示野生型小鼠拟杆菌门Muribaculaceae属和厚壁菌门瓦丁梭菌BB60群(VadinBB60 -group)、杜氏乳杆菌(Dubosiella)、瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus)等益生菌富集。Muribaculaceae属在肠道的能量代谢、血糖血脂等发挥作用。Dubosiella的代谢产物为丁酸,可预防、改善肥胖。VadinBB60-group的代谢产物为短链脂肪酸,与丙酸盐比例呈正相关[14]。较高比例的丙酸盐会导致糖异生增加,减低肥胖[15]。提示野生型小鼠的标志菌在调节血糖中发挥作用。在中国人群中,拟杆菌属(Bacteroides)和另枝菌属(Alistipes)在2型糖尿病患者中比在糖代谢正常的人中更为丰富。另外,它们也与胆固醇水平升高相关[16]。糖尿病患者的幽门螺旋杆菌感染率明显更高[17]。以上临床结果与本实验中db/db小鼠螺旋杆菌属、Alistipes和Bacteroides富集相符。大豆不溶性膳食纤维通过增加乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)和毛螺菌科NK4A136组(Lachnospiraceae _NK4A136_group)与肥胖相关的潜在有益菌的相对丰度,预防高脂肪饮食喂养小鼠肥胖[18]。黄芩和黄连处理增加产生短链脂肪酸的细菌Prevotellaceae UCG-001等的富集,改善2型糖尿病大鼠糖脂代谢[19]。提示本实验恒古骨伤愈合剂通过Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group、Lactobacillus和Prevotellaceae等的富集,调节糖脂代谢。而广谱抗生素组中变形菌门γ-和β-变形菌纲的相关致病菌富集,提示抗生素虽然降低血糖,但可能导致重要的肠道微生物共生体从各群体中消失,使能够提供重要健康益处的细菌物种减少[20]。此外,本实验发现恒古骨伤愈合剂联合广谱抗生素干预组中,表现为有益菌Parabacteroides、Akkermansia和有害菌Morganellaceae、Alphaproteobacteria并存富集的状态。提示尽管ABS、OK和联合干预下db/db小鼠血糖及胰岛素抵抗均有所改善,但从肠道优势菌群富集的角度,各干预组涉及的具体调控机制可能有所不同。已有研究表明狄氏副拟杆菌胞外多糖粗提物具良好的免疫调节功能,由可减轻肥胖、缓解结肠炎[21]。阿克曼菌与肥胖、糖尿病、肝脏和心血管疾病等的发生发展相关,在调节机体代谢紊乱方面发挥着至关重要的作用[22-23]。恒古骨伤愈合剂改善抗生素导致肠道微生态紊乱,增加改善糖代谢的有益微生物的富集。推测恒古骨伤愈合剂改善血糖、胰岛素抵抗与这些有益微生物的富集有关,值得进一步探讨。

综上,广谱抗生素、恒古骨伤愈合剂单独和联合作用,均降低2型糖尿病db/db小鼠空腹血糖和胰岛素抵抗。且恒古骨伤愈合剂可改善抗生素对db/db肠道微生态损害。

-

表 1 菲律宾农村地区常见寄生虫病患病率(%)

Table 1. Prevalence of common parasitic diseases in rural areas of the Philippines(%)

感染寄生虫种类 患病率 成人 儿童 总体 血吸虫 13.7 11.6 12.5 土源性线虫 64.0 65.1 64.6 蛔虫 27.0 35.1 31.5 鞭虫 50.5 55.1 53.1 钩虫 10.0 2.7 5.9 土源性线虫与血吸虫混合感染 10.5 9.1 9.7 表 2 “一带一路”沿线南亚、东南亚国家寄生虫病流行情况(1)

Table 2. The prevalence of parasitic diseases in South and Southeast Asian countries along the “One Belt and One Road” (1)

国家 寄生虫种 年份 风险人数 病例数(例) 患病率 病死率 参考文献 印度 间日疟 2014 0.3% [4] 弓形虫 1991 57%(马翁族人) [21] 巴基斯坦 疟原虫 2012 450万 [5] 皮肤利什曼原虫 2005 738 [27] 孟加拉国 疟原虫 2013 3.1%~36% [8] 阿富汗 疟原虫 2002 12 786 [10] 疟原虫 2015 850万 61 362 [10] 疟原虫 2016 1 009 [10] 尼泊尔 疟疾 1985 42 321 [11] 蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫 2014 8.9% [32] 人芽囊原虫 2014 6.9% [32] 蛔虫 2014 15.6% [32] 鞭虫 2014 1.2% [32] 钩虫 2014 10.4% [32] 带绦虫 2014 3.4% [32] 不丹 疟原虫 2010 436 [12] 印度尼西亚 疟原虫 2007 2.89‰ [15] 弓形虫 2017 50% [24] 阴道毛滴虫 2005 15.1% [33] 日本血吸虫 2019 0.3%~4.8%(纳普、林杜河谷地区) [42] 疟原虫 2017 6500 万0.9‰ [15] 土源性线虫 2008 61% [42] 丝虫 2014 4.7% [42] 泰国 疟原虫 2000 2.61% [20] 疟原虫 2016 18 758 0.28% [20] 人芽囊原虫 2017 4.0% [38] 蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫 2017 0.6% [38] 钩虫 2008 8.0% [48] 粪类圆线虫 2008 0.9% [48] 鞭虫 2008 0.3% [48] 旋毛虫 2008 0.24~3.9/十万 [48] 马来西亚 弓形虫 2011 10%~77% [21] 结肠内阿米巴 2013 3.2% [35] 溶组织内阿米巴 2013 1.8% [35] 蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫 2013 1.8% [35] 人芽囊原虫 2013 1.2% [35] 鞭虫 2013 20.2%(儿童) [35] 蛔虫 2013 10.5%(儿童) [35] 钩虫 2013 6.7%(儿童) [35] 粪类圆线虫 2019 13.7%(小学生) [46] 猪囊虫 1996 2.2%(农村人口) [58] 表 2 “一带一路”沿线南亚、东南亚国家寄生虫病流行情况(2)

Table 2. The prevalence of parasitic diseases in South and Southeast Asian countries along the “One Belt and One Road” (2)

国家 寄生虫种 年份 风险人数 病例数(例) 患病率 病死率 参考文献 菲律宾 溶组织内阿米巴 2018 12.1% [36] 蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫 2018 4.5% [36] 人芽囊原虫 2018 34.4% [36] 日本血吸虫 2019 670万 74.5% [41] 越南 弓形虫 2013 1~24% [26] 蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫 2013 4.1% [26] 带绦虫 2013 0.2-7.2% [26] 缅甸 人芽囊原虫 2019 6.29%(中缅边境地区) [37] 鞭虫 2010 13.3% [47] 蛲虫 2010 8.1% [47] 华支睾吸虫 2010 0.7% [47] 丝虫 2018 2.63% [65] 老挝 钩虫 2018 87% [49] 鞭虫 2018 33% [49] 粪类圆线虫 2018 45% [49] 柬埔寨 鞭虫 2018 4.1% [51] -

[1] WHO. World malaria report 2021: Regional data and trends. https://wwwwhoint/publications/m/item/WHO-UCN-GMP-2021092021. [2] Singh V,Mishra N,Awasthi G,et al. Why is it important to study malaria epidemiology in India[J]. Trends Parasitol,2009,25(10):452-427. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.06.004 [3] Kochar D K,Das A,Kochar A,et al. A prospective study on adult patients of severe malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum,Plasmodium vivax and mixed infection from Bikaner,northwest India[J]. J Vector Borne Dis,2014,51(3):200-210. [4] Rahimi B A,Thakkinstian A,White N J,et al. Severe vivax malaria:a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies since 1900[J]. Malar J,2014,13:481. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-481 [5] Umer M F, Zofeen S, Majeed A, et al. Spatiotemporal Clustering Analysis of Malaria Infection in Pakistan[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2018, 15(6): 1202. [6] Yasinzai M I,Kakarsulemankhel J K. Prevalence of human malaria infection in bordering areas of East Balochistan,adjoining with Punjab:Loralai and Musakhel[J]. J Pak Med Assoc,2009,59(3):132-135. [7] Tariq A,Adnan M,Amber R,et al. Ethnomedicines and anti-parasitic activities of Pakistani medicinal plants against Plasmodia and Leishmania parasites[J]. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob,2016,15(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0170-0 [8] Islam N,Bonovas S,Nikolopoulos G K. An epidemiological overview of malaria in Bangladesh[J]. Travel Med Infect Dis,2013,11(1):29-36. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.01.004 [9] Alam M S,Khan M G,Chaudhury N,et al. Prevalence of anopheline species and their Plasmodium infection status in epidemic-prone border areas of Bangladesh[J]. Malar J,2010,9:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-15 [10] Safi N H,Ahmadi A A,Nahzat S,et al. Evidence of metabolic mechanisms playing a role in multiple insecticides resistance in Anopheles stephensi populations from Afghanistan[J]. Malar J,2017,16(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1744-9 [11] Rijal K R,Adhikari B,Ghimire P,et al. Epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax Malaria Infection in Nepal[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2018,99(3):680-687. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0373 [12] Yangzom T,Gueye C S,Namgay R,et al. Malaria control in Bhutan:case study of a country embarking on elimination[J]. Malar J,2012,11:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-9 [13] Grignard L,Shah S,Chua T H,et al. Natural Human Infections With Plasmodium cynomolgi and Other Malaria Species in an Elimination Setting in Sabah,Malaysia[J]. J Infect Dis,2019,220(12):1946-1949. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz397 [14] Singh B,Daneshvar C. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Malaysia[J]. Med J Malaysia,2010,65(3):166-172. [15] Sitohang V,Sariwati E,Fajariyani S B,et al. Malaria elimination in Indonesia:halfway there[J]. Lancet Glob Health,2018,6(6):e604-e606. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30198-0 [16] Xu S, Zeng W, Ngassa Mbenda HG, et al. Efficacy of directly-observed chloroquine-primaquine treatment for uncomplicated acute Plasmodium vivax malaria in northeast Myanmar: A prospective open-label efficacy trial[J]. Travel Med Infect Dis, 2019, 10: 1499. [17] Briand V,Le Hesran J Y,Mayxay M,et al. Prevalence of malaria in pregnancy in southern Laos:a cross-sectional survey[J]. Malar J,2016,15(1):436. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1492-2 [18] Thanh P V,Van Hong N,Van Van N,et al. Epidemiology of forest malaria in Central Vietnam:the hidden parasite reservoir[J]. Malar J,2015,14:86. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0601-y [19] Bannister-Tyrrell M,Xa N X,Kattenberg J H,et al. Micro-epidemiology of malaria in an elimination setting in Central Vietnam[J]. Malar J,2018,17(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2262-0 [20] Sudathip P,Kongkasuriyachai D,Stelmach R,et al. The Investment Case for Malaria Elimination in Thailand:A Cost-Benefit Analysis[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2019,100(6):1445-1453. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0897 [21] Singh S,Nautiyal B L. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in Kumaon region of India[J]. Indian J Med Res,1991,93:247-249. [22] Ngui R,Ishak S,Chuen C S,et al. Prevalence and risk factors of intestinal parasitism in rural and remote West Malaysia[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis,2011,5(3):e974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000974 [23] Ahmad A F,Ngui R,Muhammad Aidil R,et al. Current status of parasitic infections among Pangkor Island community in Peninsular Malaysia[J]. Trop Biomed,2014,31(4):836-843. [24] Tuda J,Adiani S,Ichikawa-Seki M,et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in humans and pigs in North Sulawesi,Indonesia[J]. Parasitol Int,2017,66(5):615-618. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2017.04.011 [25] Muflikhah N D,Supargiyono,Artama W T. Seroprevalence and Risk Factor of Toxoplasmosis in Schizophrenia Patients Referred to Grhasia Psychiatric Hospital,Yogyakarta,Indonesia[J]. Afr J Infect Dis,2018,12(1 Suppl):76-82. [26] Carrique-Mas J J,Bryant J E. A review of foodborne bacterial and parasitic zoonoses in Vietnam[J]. Ecohealth,2013,10(4):465-489. doi: 10.1007/s10393-013-0884-9 [27] Khan S J,Muneeb S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan[J]. Dermatol Online J,2005,11(1):4. [28] Aerts C,Vink M,Pashtoon S J,et al. Cost Effectiveness of New Diagnostic Tools for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Afghanistan[J]. Appl Health Econ Health Policy,2019,17(2):213-230. doi: 10.1007/s40258-018-0449-8 [29] Thornton S J,Wasan K M,Piecuch A,et al. Barriers to treatment for visceral leishmaniasis in hyperendemic areas:India,Bangladesh,Nepal,Brazil and Sudan[J]. Drug Dev Ind Pharm,2010,36(11):1312-1319. doi: 10.3109/03639041003796648 [30] Singh B B,Sharma R,Sharma J K,et al. Parasitic zoonoses in India:an overview[J]. Rev Sci Tech,2010,29(3):629-637. doi: 10.20506/rst.29.3.2007 [31] Galgamuwa L S,Dharmaratne S D,Iddawela D. Leishmaniasis in Sri Lanka:spatial distribution and seasonal variations from 2009 to 2016[J]. Parasit Vectors,2018,11(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2647-5 [32] Devleesschauwer B,Ale A,Torgerson P,et al. The burden of parasitic zoonoses in Nepal:a systematic review[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis,2014,8(1):e2634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002634 [33] Mawu F O,Davies S C,McKechnie M,et al. Sexually transmissible infections among female sex workers in Manado,Indonesia,using a multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based reverse line blot assay[J]. Sex Health,2011,8(1):52-60. doi: 10.1071/SH10023 [34] Tanudyaya F K,Rahardjo E,Bollen L J,et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk behavior among female sex workers in nine provinces in Indonesia,2005[J]. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health,2010,41(2):463-473. [35] Sinniah B,Hassan A K,Sabaridah I,et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among communities living in different habitats and its comparison with one hundred and one studies conducted over the past 42 years (1970 to 2013) in Malaysia[J]. Trop Biomed,2014,31(2):190-206. [36] Weerakoon K G,Gordon C A,Williams G M,et al. Co-parasitism of intestinal protozoa and Schistosoma japonicum in a rural community in the Philippines[J]. Infect Dis Poverty,2018,7(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0504-6 [37] Gong B,Liu X,Wu Y,et al. Prevalence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis in ethnic minority groups on both sides of the China-Myanmar border,and assessment of risk factors[J]. Parasite,2019,26:46. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2019046 [38] Punsawad C,Phasuk N,Bunratsami S,et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection and associated risk factors among village health volunteers in rural communities of southern Thailand[J]. BMC Public Health,2017,17(1):564. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4486-2 [39] Kang G,Mathew M S,Rajan D P,et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in rural Southern Indians[J]. Trop Med Int Health,1998,3(1):70-75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00175.x [40] Traub R J,Robertson I D,Irwin P,et al. Thompson RC. Humans,dogs and parasitic zoonoses--unravelling the relationships in a remote endemic community in northeast India using molecular tools[J]. Parasitol Res,2003,90(Suppl 3):S156-S157. [41] Francisco I,Jiz M,Rosenbaum M,et al. Knowledge,attitudes and practices related to schistosomiasis transmission and control in Leyte,Philippines[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis,2019,13(5):e0007358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007358 [42] Lee J,Ryu JS. Current Status of Parasite Infections in Indonesia:A Literature Review[J]. Korean J Parasitol,2019,57(4):329-339. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2019.57.4.329 [43] Karthikeyan K,Thappa D M,Jeevankumar B. Cutaneous larva migrans of the penis[J]. Sex Transm Infect,2003,79(6):500. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.500 [44] Krsak M,Patel N U,Poeschla E M. Case Report:Hepatic Fascioliasis in a Young Afghani Woman with Severe Wheezing,High-Grade Peripheral Eosinophilia,and Liver Lesions:A Brief Literature Review[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2019,100(3):588-590. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0625 [45] Liwanag H J,Uy J,Bataller R,et al. Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis and Schistosomiasis in Children of Poor Families in Leyte,Philippines:Lessons for Disease Prevention and Control[J]. J Trop Pediatr,2017,63(5):335-345. [46] Al-Mekhlafi H M,Nasr N A,Lim Y A L,et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Strongyloides stercoralis infection among Orang Asli schoolchildren:new insights into the epidemiology,transmission and diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in Malaysia[J]. Parasitology,2019,146(12):1602-14. doi: 10.1017/S0031182019000945 [47] Hotez P J,Ehrenberg J P. Escalating the global fight against neglected tropical diseases through interventions in the Asia Pacific region[J]. Adv Parasitol,2010,72:31-53. [48] Kaewpitoon N,Kaewpitoon S J,Pengsaa P. Food-borne parasitic zoonosis:distribution of trichinosis in Thailand[J]. World J Gastroenterol,2008,14(22):3471-3475. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3471 [49] Htun N S N,Odermatt P,Paboriboune P,et al. Association between helminth infections and diabetes mellitus in adults from the Lao People's Democratic Republic:a cross-sectional study[J]. Infect Dis Poverty,2018,7(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0488-2 [50] Liao C W,Chiu K C,Chiang I C,et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Intestinal Parasitic Infection in Schoolchildren in Battambang,Cambodia[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2017,96(3):583-588. [51] Phosuk I,Sanpool O,Thanchomnang T,et al. Molecular Identification of Trichuris suis and Trichuris trichiura Eggs in Human Populations from Thailand,Lao PDR,and Myanmar[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2018,98(1):39-44. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0651 [52] Khieu V,Furst T,Miyamoto K,et al. Is Opisthorchis viverrini Emerging in Cambodia?[J]. Adv Parasitol,2019,103:31-73. [53] Ng-Nguyen D,Stevenson M A,Traub R J. A systematic review of taeniasis,cysticercosis and trichinellosis in Vietnam[J]. Parasit Vectors,2017,10(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2085-9 [54] Aung A K,Spelman D W. Taenia solium Taeniasis and Cysticercosis in Southeast Asia[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2016,94(5):947-954. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0684 [55] Prasad K N,Chawla S,Jain D,et al. Human and porcine Taenia solium infection in rural north India[J]. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg,2002,96(5):515-516. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(02)90423-2 [56] Foo S S,Selvan V S,Clarke M J,et al. Unusual cause of seizures in Singapore:neurocysticercosis[J]. Singapore Med J,2008,49(6):e147-150. [57] Xu J M,Acosta L P,Hou M,et al. Seroprevalence of cysticercosis in children and young adults living in a helminth endemic community in leyte,the Philippines[J]. J Trop Med,2010,2010:603174. [58] Noor Azian M Y,Hakim S L,Sumiati A,et al. Seroprevalence of cysticercosis in a rural village of Ranau,Sabah,Malaysia[J]. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health,2006,37(1):58-61. [59] Wandra T,Ito A,Swastika K,et al. Taeniases and cysticercosis in Indonesia:past and present situations[J]. Parasitology,2013,140(13):1608-1616. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013000863 [60] Zein U,Siregar S,Janis I,et al. Identification of a previously unidentified endemic region for taeniasis in North Sumatra,Indonesia[J]. Acta Trop,2019,189:114-116. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.10.004 [61] Salim L,Ang A,Handali S,et al. Seroepidemiologic survey of cysticercosis-taeniasis in four central highland districts of Papua,Indonesia[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg,2009,80(3):384-388. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.384 [62] McCleery E J,Patchanee P,Pongsopawijit P,et al. Taeniasis among Refugees Living on Thailand-Myanmar Border,2012[J]. Emerg Infect Dis,2015,21(10):1824-1826. [63] Anantaphruti M T,Okamoto M,Yoonuan T,et al. Molecular and serological survey on taeniasis and cysticercosis in Kanchanaburi Province,Thailand[J]. Parasitol Int,2010,59(3):326-330. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.03.007 [64] Sato M O,Sato M,Yanagida T,et al. Taenia solium,Taenia saginata,Taenia asiatica,their hybrids and other helminthic infections occurring in a neglected tropical diseases' highly endemic area in Lao PDR[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis,2018,12(2):e0006260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006260 [65] Dickson B F R,Graves P M,Aye N N,et al. The prevalence of lymphatic filariasis infection and disease following six rounds of mass drug administration in Mandalay Region,Myanmar[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis,2018,12(11):e0006944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006944 -

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: