-

摘要: 获得性免疫缺陷综合征(acquired immune deficiency syndrome,AIDS)是一种由人类免疫缺陷病毒(HIV)引发的全身性疾病。趋化因子配体3[Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3,CCL3]作为趋化因子家族的重要成员,在艾滋病发病机制中扮演着不可或缺的角色。CCL3通过阻止HIV进入靶细胞,激活免疫细胞增强抗病毒能力,并调节炎症反应和影响疾病进展,发挥重要的抗病毒和免疫调节作用。大量研究表明CCL3基因拷贝数、特定T细胞反应、CCL3多态性以及其参与的信号通路均影响HIV的发展及病毒载量。综述了CCL3通过阻断HIV-1进入免疫细胞、诱导抗病毒蛋白表达抑制病毒复制,以及其多态性和等位基因对HIV感染及进展的影响等多方面对艾滋病的作用,以期为艾滋病防治策略提供新的理论支撑。Abstract: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a systemic disease caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (CCL3), as a vital member of the chemokine family, plays an indispensable role in the pathogenesis of AIDS. In the context of AIDS, CCL3 exerts significant antiviral and immunomodulatory effects by preventing HIV entry into target cells, activating immune cells to enhance antiviral capabilities, and modulating inflammatory responses, thereby influencing disease progression. Numerous studies have demonstrated that CCL3 gene copy number, specific T-cell responses, CCL3 polymorphisms, and the signaling pathways it participates in all influence the development of HIV and viral load. This article comprehensively reviews the multifaceted roles of CCL3 in AIDS, including its ability to block HIV-1 entry into immune cells, inducing the expression of antiviral proteins to inhibit viral replication, as well as the influence of its polymorphisms and alleles on HIV infection and disease progression, aiming to provide novel theoretical support for AIDS prevention and treatment strategies.

-

艾滋病又称获得性免疫缺陷综合征(acquired immunodeficiency syndrome,AIDS),由艾滋病毒(human immunodeficiency virus,HIV)感染引起,是一种高度恶性的传染病[1−2],HIV特异性攻击CD4+ T淋巴细胞,导致免疫系统崩溃,增加患者对其他疾病(如带状疱疹、肺结核及恶性肿瘤)的易感性[2−3]以及多种神经系统并发症[4],鉴于其高病死率和快速传播的特性,艾滋病已成为全球公共卫生领域的重大挑战[5−6]。至2022年底,中国内地存活的AIDS患者已超过百万,新报告病例数持续上升,凸显了深入研究和有效治疗策略的紧迫性[7-8]。研究显示,CCL3[Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3,CCL3]与其受体CCR5的结合能显著抑制HIV-1的复制与传播,且使用CCR5拮抗剂(如马拉韦罗)可有效阻止HIV入侵和复制[9]。然而,CCL3抑制HIV的具体机制尚未完全阐明。本文旨在综述CCL3参与HIV抑制的最新研究进展,为未来的研究和临床应用提供参考。通过深入解析CCL3的作用机制,为艾滋病的治疗方法和疫苗研发开辟了新的思路和方向。

1. CCL3的基本特性与功能

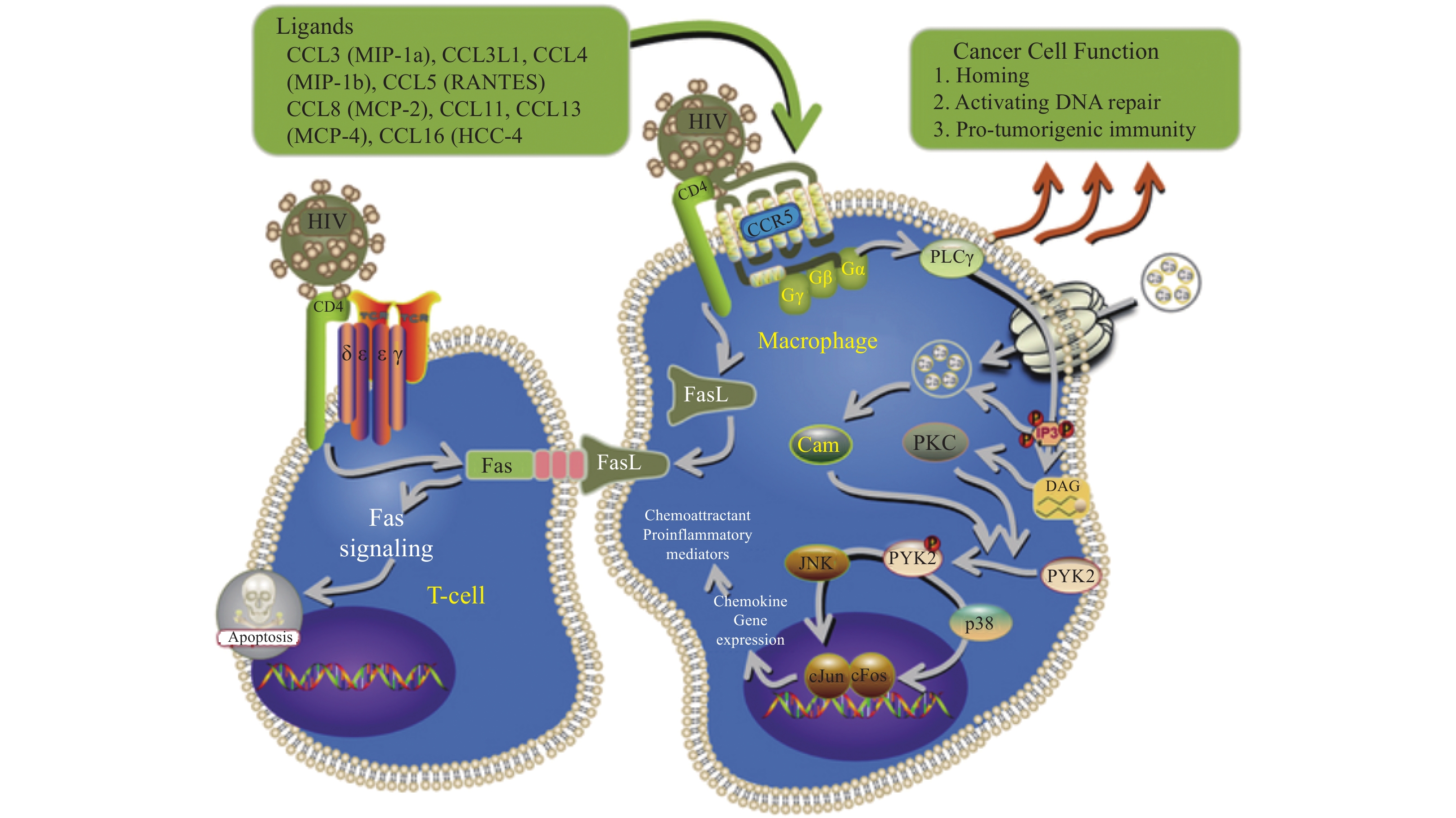

CCL3,亦被称为巨噬细胞炎性蛋白-1α(macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha,MIP-1α),归属于CC亚家族。1988年,研究者从经内毒素刺激的小鼠巨噬细胞培养上清中分离并提纯了一种与肝素结合的蛋白质,将其命名为MIP-1α[10]。2000年MIP-1α被重新命名为CCL3[11]。CCL3在人体中定位于第17号染色体,其前体蛋白质由92个氨基酸组成,而成熟形态的蛋白质则包含69个氨基酸,其相对分子质量大约为8 kDa[10]。CCL3能有效结合CCR5,从而阻断HIV-1进入CD4+ T细胞和其他免疫细胞,这种结合不仅直接抑制了病毒的入侵,还通过激活信号通路诱导抗病毒蛋白的表达,进一步抑制HIV-1的复制[12],见图1[13]。多项研究表明,CCR5作为HIV-1的主要核心受体,其与CCL3的相互作用及其拮抗剂[9](如TAK-779和马拉韦罗)能够有效阻止病毒进入CD4+ T细胞。比如用PolyI:C刺激人类宫颈上皮细胞(Humancervial epithelial cells,HCEs)后CCL3显著上调[14];而免疫小鼠的脾细胞分泌了多种细胞因子,如IFN-γ、IL-2等,这些因子在CCL3等趋化因子的作用下,能有效诱导单核巨噬细胞、T淋巴细胞以及自然杀伤细胞等向炎症部位聚集,进而释放包括CCL3在内的多种趋化因子从而增强免疫反应,发挥其在机体免疫防御和炎症反应中的关键作用[15]。

2. CCL3多态性对HIV感染及进展的影响

艾滋病作为一种由免疫缺陷引发的恶性传染病,其发病机制错综复杂,涉及多条信号通路的交互作用,免疫细胞与趋化因子的广泛参与,共同编织成一个复杂的炎症网络。近年来,趋化因子CCL3在HIV感染中的作用逐渐明晰。研究表明,HIV感染者血浆中CCL3水平显著升高[16],且与脑脊液中HIV-1 RNA水平正相关[17-18],提示CCL3与HIV-1复制之间的紧密联系。此外,Wright SM等[19]的体外实验表明,CCL3能有效抑制牛免疫缺陷病毒的表达,而CCL3表现型缺陷的婴儿则面临更高的HIV-1感染风险[20],进一步提示了CCL3在抑制HIV复制中的潜在作用。值得注意的是,CCL3在HIV感染不同阶段的表达呈现出显著差异,急性期表达受到抑制[21],慢性期则未见明显变化,凸显了其在HIV感染过程中的复杂调控作用。

2.1 CCL3的等位基因的特定突变组合抑制HIV感染

CCL3的等位基因的特定突变组合可能是决定HIV抵抗表型的关键,研究发现,哥伦比亚个体的CCL3基因中C-C单倍型与HIV-1感染易感性相关,而T-T单倍型与HIV-1抵抗性相关,且特定单倍型组合与HIV-1抵抗性显著相关[22]。与撒哈拉以南非洲人群中患者类似,CCL3的HapA1单倍型保护胎儿免感染,其效应依赖婴儿携带;而Hap-A3则与产时传播风险增加有关,与母体携带相关,虽然HapA1与高CCL3L拷贝数正相关,但预防感染并非简单累加,任一因素的存在即能显著保护效果,然而,尼日利亚人群的差异表现提示两者无必然连锁,凸显了研究的复杂性和人群特异性[23]。而CCL3L1基因拷贝数与病毒载量之间的负相关关系也进一步证实CCL3等位基因的特定突变组合抑制HIV感染[24-25]。综上所述,CCL3等位基因的特定突变组合对HIV-1感染有重要影响,且存在人群差异性。CCL3L1基因拷贝数与病毒载量负相关,进一步证实其抑制作用。未来研究需细致探讨遗传变异在不同人群中的效应,为HIV防治提供精准、个性化策略。

2.2 CCL3多态性与艾滋病的关系受地域和人群差异影响

尽管CCL3及其相关基因在HIV/AIDS研究中的重要性已得到广泛认可,但CCL3多态性对HIV感染发展的影响仍需深入探究[26],以阐明其具体机制。先前的研究表明,CCL3基因中的SNP[27](如rs5029410C与rs34171309A)与HIV病毒载量及感染风险相关,其中,rs5029410C与较低的病毒载量相关,而rs34171309A则与增加HIV感染风险有关。Gonzalez E等[28]则揭示了一个包含两个CCL3内含子1SNP的单倍型,该单倍型与非洲裔美国人(AAs)对HIV-1感染的抵抗力相关,同时也与欧洲裔美国人(EAs)加速进展至艾滋病(AIDS)有关。基于这些研究,Modi WS等[29]在2006年的研究中进一步发现,在非裔美国人中,三个位于CCL3基因内的SNP(ss46566437、ss46566438和ss46566439)在高度暴露但持续未感染HIV-1的个体中频率显著升高。相比之下,在欧洲裔美国人中,七个高度相关的SNP则与更快的疾病进展至AIDS相关。这些SNP跨越了

36562 bp的区域,覆盖了CCL3、CCL4和CCL18三个基因。然而,由于该区域内存在广泛的连锁不平衡,目前尚无法明确确定特定的SNP或单个基因为致病因素,需要更大样本量、更精细的基因分型以及考虑基因-基因和环境交互作用,以进一步揭示CCL3基因变异在HIV-1/AIDS发病机制中的作用。此外,地域和人群差异也可能影响CCL3多态性与艾滋病的关系,这进一步强调了该领域研究的复杂性和异质性。例如,江西人群[30]的CCL3L1基因拷贝数与HIV易感性无显著相关,但与感染进程有一定相关性,这一发现揭示了CCL3基因变异在HIV-1/AIDS发病机制中的作用可能因地域和人群差异而有所不同。3. CCL3在HIV/SIV感染中的多重防御作用

3.1 CCL3通过各种免疫细胞作用于HIV

在HIV及SIV感染的研究中,CCL3作为一种关键趋化因子,其多层次、多途径的防御机制逐渐得到揭示。多种免疫细胞,包括CD4+ T细胞、Vδ1 T细胞、单核细胞、巨噬细胞及NK细胞,在感染后能分泌CCL3,以有效阻断HIV病毒的入侵和传播[31-32]。特别是NK细胞,通过表达NKp30等受体和因子,显著上调CCL3的表达,从而增强机体的抗HIV病毒能力[33−38],而在共感染HBV和HIV/HBV的患者中,NK细胞展现出不同的特征,其中表达KLRC2的NK细胞伴随更高丰度的CCL3/CCL4富集,这些特征与病毒载量负相关,为治疗策略提供了新的见解[39]。同时,单核巨噬细胞系统也在多种外部因素(如蓝舌病毒、神经肽、白色链珠菌等)的刺激下上调CCL3,积极参与免疫应答过程[40-41]。进一步的研究发现,CCL3在女性生殖道及SIV-恒河猴模型中与早期募集的巨噬细胞和浆细胞样树突状细胞密切相关,这些细胞产生CCL3,诱导CD4+ T细胞的募集,进而影响局部病毒的扩张[42−44]。同时,HIV-1的Nef蛋白与CXCR4受体的相互作用也能激活细胞释放CCL3,参与免疫细胞的募集与激活,进一步丰富了CCL3在HIV感染中的功能图谱[45]。值得注意的是,在HIV/SIV感染导致的肝脏疾病,巨噬细胞分泌的CCL3能够吸引表达CCR5的靶细胞迁移至肝脏,从而促进病毒的复制和炎症反应,这一发现凸显了CCL3在病毒传播和免疫应答中的核心作用[46]。

3.2 CCL3在HIV中作用的信号通路

多项研究表明,CCL3等化学趋化因子不仅通过传统的GPCR途径传递信号,还通过CD44等非经典途径激活细胞内信号通路,如NF-κB信号通路,这些通路在HIV的传播与免疫应答中发挥着至关重要的作用[47-48]。特别值得注意的是,NF-κB信号通路在HIV-1的感染和转录调控中占据了核心地位,它既能促进病毒基因的表达,又能在一定程度上抑制炎症状态的产生,显示出其复杂而多面的功能[49]。进一步的研究揭示,NF-κB与TNF信号的相互作用对CCL3的产生以及HIV-1的转录具有重要影响,因此,NF-κB活化的调节因子可能是对抗HIV-1的一种有前景的治疗策略[50-51]。另一方面,SLAMF7作为一种免疫调控因子,通过抑制NF-κB信号通路来影响免疫细胞的活性,从而在免疫调控中发挥着重要作用。SLAMF7信号的激活不仅能下调CCR5的表达,还能增加特定趋化因子(如CCL3L1)的水平,这一发现为理解HIV感染中的免疫应答提供了新的视角[52]。因此,探索SLAMF7与CCL3等趋化因子及NF-κB信号通路之间的相互作用机制,不仅有助于我们更深入地理解HIV感染的免疫病理过程,还可能为开发针对HIV的新型免疫调节疗法提供潜在的靶点,为艾滋病的治疗带来新的希望。

4. CCL3在特定人群与疾病状态中的作用

赞比亚女性生殖器血吸虫病(female genital schistosomiasis,FGS)女性宫颈阴道中,尽管宫颈阴道的整体细胞因子浓度无显著差异,但FGS负担较高者Th2细胞因子(包括CCL3相关的IL-4、IL-5)及促炎因子表达显著上升,提示FGS可能通过改变生殖道免疫环境,尤其是CCL3相关因子的变化,增加HIV-1易感性[53]。低水平病毒血症患者的CD4+ T细胞转录组特性显示,与病毒抑制者相比,其CD4+ T细胞具有独特的mRNA表达谱,特别是抗HIV趋化因子CCL3显著上调,这可能促进HIV-1复制并触发病毒潜伏期的再激活,加剧病毒失活风险[54]。而在HIV高暴露血清阴性商业性工作者血液中,单核细胞CCL3表达显著上调,与树突状细胞的抗病毒及调节功能紧密相关,这些功能与天然免疫抗HIV感染密切相关[55]。另有研究发现,接受抑制治疗的女性患者体内CCL3等细胞因子水平高于男性,可能导致更高的免疫激活率;且通过PLS-DA模型预测出生性别时,CCL3是关键因子,表明其在性别差异导致的免疫激活和HIV宿主维持中起重要作用[56]。综上,CCL3在HIV感染中展现出复杂且双面的作用:在某些与HIV共病的疾病中既可促进病毒复制和潜伏再激活,增加HIV易感性和疾病进展风险;又能在特定情境下发挥抗病毒作用,增强宿主天然免疫应答,保护个体免受HIV感染。这体现了宿主免疫系统的复杂性和HIV感染机制的多样性。

5. CCL3在HIV感染治疗策略中的应用前景

研究表明,使用埃博拉病毒包膜糖蛋白(ebola virus envelope glycoprotein,EboGP)伪型的HIV病毒样颗粒能显著增强HIV特异性免疫反应,特别是促进Th2细胞因子CCL3在免疫小鼠脾细胞中高表达,这有助于HIV感染初期的细胞介导保护,并为基于树突状细胞的新型HIV疫苗策略提供支持[57]。疫苗中CCL3表达的显著变化揭示了其在调控疫苗诱导免疫反应中的关键作用,为HIV疫苗的研发提供了新的思路[58]。在喀麦隆HIV-1感染青少年中,CCL3在病毒治疗失败时高度表达,与抗药性突变时的免疫反应相关,表明其在HIV感染炎症过程中起关键作用,可能作为抗逆转录病毒治疗(antiretroviral therapy,ART)反应不佳的标志物,有助于优化儿科艾滋病毒控制策略[59]。此外,南非和乌干达地区的HIV暴露前预防(pre-exposure prophylaxis,PrEP)试验显示,CCL3与CCL4在PrEP干预后显著上升,通过阻断病毒与CCR5 HIV-1共受体的连接增强防护效果,凸显了CCL3在PrEP免疫调节中的核心地位,并为优化PrEP策略提供了新线索[60]。综上所述,CCL3在HIV疫苗开发、预防及药物治疗中具有重要意义,作为增强HIV特异性免疫反应的关键因子,在基于EboGP伪型的HIV病毒样颗粒疫苗策略中发挥重要作用,为新型HIV疫苗研发开辟新路径;其高度表达被识别为治疗失败与抗药性突变的潜在标志物,为评估治疗效果、调整治疗方案提供依据;在PrEP策略中,不仅强调了CCL3在PrEP免疫调节机制中的核心作用,而且为进一步优化PrEP策略、提升HIV预防效能提供了重要的科学依据和研究线索,具有潜在的学术价值和实际应用前景。

6. 小结

CCL3作为一种核心趋化因子,在机体对抗HIV及SIV感染的过程中,展现了其多层次、多途径的防御能力。它不仅能够直接干预HIV的入侵过程,还能通过激活信号通路,诱导抗病毒蛋白的表达,从而进一步抑制HIV的复制。此外,CCL3在调控免疫细胞的招募与激活方面也同样发挥着关键作用,构建了一个动态的、相互增强的免疫应答网络。然而,尽管已经认识到CCL3在HIV感染中的重要性,但其具体的作用机制仍有许多未解之谜,特别是CCL3多态性如何影响HIV的免疫逃逸机制,以及不同地域和人群中CCL3多态性的分布和功能差异,这些问题都亟待解决。为了深化对CCL3与艾滋病关系的理解,并为新的预防和治疗策略提供线索,未来的研究需要从多个方面入手。首先,必须阐明CCL3多态性如何具体影响HIV的免疫逃逸机制,以及不同人群间CCL3基因多态性对HIV易感性及疾病进展的具体影响,为个性化治疗策略的制定提供坚实的理论基础。其次,应深入探讨CCL3在特定疾病状态下对HIV感染的复杂作用,同时考虑如何利用CCL3多态性来开发新的艾滋病预防和治疗策略,以揭示其在不同疾病环境中的双重角色,并探索其在HIV疫苗开发、预防及药物治疗中的前景。此外,鉴于HIV的高突变性,研究CCL3及其相关药物在使用过程中的耐药性问题也至关重要,以便及时调整治疗方案,提高治疗效果。综上所述,CCL3与艾滋病的研究领域依旧广阔且充满挑战与机遇。通过持续深入的研究,笔者有望更全面地揭示CCL3在HIV感染中的作用机制,特别是其多态性在免疫逃逸和地域分布上的差异,为艾滋病的防治提供新的思路和方法,从而造福更多的患者。

-

[1] Angin M,Sharma S,King M,et al. HIV-1 infection impairs regulatory T-cell suppressive capacity on a per-cell basis[J]. J Infect Dis,2014,210(6):899-903. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu188 [2] Sheykhhasan M,Foroutan A,Manoochehri H,et al. Could gene therapy cure HIV?[J]. Life Sci,2021,277:119451. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119451 [3] Morty R E,Morris A. World AIDS Day 2021: highlighting the pulmonary complications of HIV/AIDS[J]. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol,2021,321(6):L1069-L1071. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00471.2021 [4] McEntire C R S,Fong K T,Jia D T,et al. Central nervous system disease with JC virus infection in adults with congenital HIV[J]. Aids,2021,35(2):235-244. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002734 [5] 热伊拜·亚迪佧尔,陈晶,杨建东,等. 新疆维吾尔自治区2007-2015年HIV/AIDS病例空间自相关分析[J]. 中国艾滋病性病,2017,23(4):292-295. [6] Pang X,Wei H,Huang J,et al. Patterns and risk of HIV-1 transmission network among men who have sex with men in Guangxi,China[J]. Sci Rep,2021,11(1):513. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79951-2 [7] 韩孟杰. 我国艾滋病流行形势分析和防治展望[J]. 中国艾滋病性病,2023,29(3):247-250. [8] 刘丽丽,王庆,潘振强. 艾滋病危害宣传的自省式健康教育在艾滋病预防控制中的应用分析[J]. 中国医药指南,2020,18(5):143-144. [9] Aldinucci D,Borghese C,Casagrande N. The CCL5/CCR5 axis in cancer progression[J]. Cancers (Basel),2020,12(7):1765. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071765 [10] Wolpe S D,Davatelis G,Sherry B,et al. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties[J]. J Exp Med,1988,167(2):570-581. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.570 [11] Zlotnik A,Yoshie O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity[J]. Immunity,2000,12(2):121-127. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80165-X [12] Allen F,Bobanga I D,Rauhe P,et al. CCL3 augments tumor rejection and enhances CD8(+) T cell infiltration through NK and CD103(+) dendritic cell recruitment via IFNγ[J]. Oncoimmunology,2018,7(3):e1393598. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1393598 [13] Jiao X,Nawab O,Patel T,et al. Recent advances targeting CCR5 for cancer and its role in immuno-oncology[J]. Cancer Res,2019,79(19):4801-4807. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1167 [14] Xu X Q,Guo L,Wang X,et al. Human cervical epithelial ccells release antiviral factors and inhibit HIV replication in macrophages[J]. J Innate Immun,2019,11(1):29-40. doi: 10.1159/000490586 [15] Ao Z,Wang L,Azizi H,et al. Development and evaluation of an ebola virus glycoprotein mucin-like domain replacement system as a new dendritic cell-targeting vaccine approach against HIV-1[J]. J Virol,2021,95(15):e0236820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02368-20 [16] Yin X,Wang Z,Wu T,et al. The combination of CXCL9,CXCL10 and CXCL11 levels during primary HIV infection predicts HIV disease progression[J]. J Transl Med,2019,17(1):417. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-02172-3 [17] Christo P P,Vilela Mde C,Bretas T L,et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of chemokines in HIV infected patients with and without opportunistic infection of the central nervous system[J]. J Neurol Sci,2009,287(1-2):79-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.09.002 [18] Jennes W,Sawadogo S,Koblavi-Dème S,et al. Positive association between beta-chemokine-producing T cells and HIV type 1 viral load in HIV-infected subjects in Abidjan,Côte d'Ivoire[J]. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses,2002,18(3):171-177. doi: 10.1089/08892220252781220 [19] Wright S M,Mleczko A,Coats K S. Bovine immunodeficiency virus expression in vitro is reduced in the presence of beta-chemokines,MIP-1alpha,MIP-1beta and RANTES[J]. Vet Res Commun,2002,26(3):239-250. doi: 10.1023/A:1015209806058 [20] Meddows-Taylor S,Donninger S L,Paximadis M,et al. Reduced ability of newborns to produce CCL3 is associated with increased susceptibility to perinatal human immunodeficiency virus 1 transmission[J]. J Gen Virol,2006,87(Pt 7): 2055-2065. [21] Petkov S,Chiodi F. Distinct transcriptomic profiles of naïve CD4+ T cells distinguish HIV-1 infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy at acute or chronic phase of infection[J]. Genomics,2021,113(6):3487-3500. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.08.014 [22] Vega J A,Villegas-Ospina S,Aguilar-Jiménez W,et al. Haplotypes in CCR5-CCR2,CCL3 and CCL5 are associated with natural resistance to HIV-1 infection in a Colombian cohort[J]. Biomedica,2017,37(2):267-273. [23] Paximadis M,Schramm D B,Gray G E,et al. Influence of intragenic CCL3 haplotypes and CCL3L copy number in HIV-1 infection in a sub-Saharan African population[J]. Genes Immun,2013,14(1):42-51. doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.51 [24] Shalekoff S,Meddows-Taylor S,Schramm D B,et al. Host CCL3L1 gene copy number in relation to HIV-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses and viral load in South African women[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr,2008,48(3):245-254. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816fdc77 [25] Lim S Y,Chan T,Gelman R S,et al. Contributions of Mamu-A*01 status and TRIM5 allele expression,but not CCL3L copy number variation,to the control of SIVmac251 replication in Indian-origin rhesus monkeys[J]. PLoS Genet,2010,6(6):e1000997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000997 [26] Gonzalez E,Kulkarni H,Bolivar H,et al. The influence of CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications on HIV-1/AIDS susceptibility[J]. Science,2005,307(5714):1434-1440. doi: 10.1126/science.1101160 [27] Hu L,Song W,Brill I,et al. Genetic variations and heterosexual HIV-1 infection: Analysis of clustered genes encoding CC-motif chemokine ligands[J]. Genes Immun,2012,13(2):202-205. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.70 [28] Gonzalez E,Dhanda R,Bamshad M,et al. Global survey of genetic variation in CCR5,RANTES,and MIP-1alpha: impact on the epidemiology of the HIV-1 pandemic[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A,2001,98(9):5199-5204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091056898 [29] Modi W S,Lautenberger J,An P,et al. Genetic variation in the CCL18-CCL3-CCL4 chemokine gene cluster influences HIV Type 1 transmission and AIDS disease progression[J]. Am J Hum Genet,2006,79(1):120-128. doi: 10.1086/505331 [30] 靳廷丽,刘丽萍,易志强,等. 江西人群CCL3L1基因拷贝数与HIV感染相关性研究[J]. 实验与检验医学,2017,35(02):163-166. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-1129.2017.02.008 [31] Casazza J P,Brenchley J M,Hill B J,et al. Autocrine production of beta-chemokines protects CMV-Specific CD4 T cells from HIV infection[J]. PLoS Pathog,2009,5(10):e1000646. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000646 [32] Walker W E,Kurscheid S,Joshi S,et al. Increased Levels of Macrophage Inflammatory Proteins Result in Resistance to R5-Tropic HIV-1 in a Subset of Elite Controllers[J]. J Virol,2015,89(10):5502-5514. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00118-15 [33] Hudspeth K,Fogli M,Correia D V,et al. Engagement of NKp30 on Vδ1 T cells induces the production of CCL3,CCL4,and CCL5 and suppresses HIV-1 replication[J]. Blood,2012,119(17):4013-4016. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390153 [34] Zhou L,Wang X,Xiao Q,et al. Flagellin restricts HIV-1 infection of macrophages through modulation of viral entry receptors and CC chemokines[J]. Viruses,2024,16(7):1063. doi: 10.3390/v16071063 [35] Phetsouphanh C,Phalora P,Hackstein C P,et al. Human MAIT cells respond to and suppress HIV-1[J]. Elife,2021,10:e50324. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50324 [36] Ellegard R,Crisci E,Andersson J,et al. Impaired NK cell activation and chemotaxis toward dendritic cells exposed to complement-opsonized HIV-1[J]. J Immunol,2015,195(4):1698-1704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500618 [37] Flórez-Álvarez L,Hernandez J C,Zapata W. NK cells in HIV-1 infection: from basic science to vaccine strategies[J]. Front Immunol,2018,9:2290. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02290 [38] Furtado Milão J,Love L,Gourgi G,et al. Natural killer cells induce HIV-1 latency reversal after treatment with pan-caspase inhibitors[J]. Front Immunol,2022,13:1067767. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1067767 [39] Rossi F W,Prevete N,Rivellese F,et al. HIV-1 Nef promotes migration and chemokine synthesis of human basophils and mast cells through the interaction with CXCR4[J]. Clin Mol Allergy,2016,14:15. doi: 10.1186/s12948-016-0052-1 [40] Dai M,Wang X,Li J L,et al. Activation of TLR3/interferon signaling pathway by bluetongue virus results in HIV inhibition in macrophages[J]. Faseb j,2015,29(12):4978-4988. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-273128 [41] Temerozo J R,Joaquim R,Regis E G,et al. Macrophage resistance to HIV-1 infection is enhanced by the neuropeptides VIP and PACAP[J]. PLoS One,2013,8(6):e67701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067701 [42] Gornalusse G G,Valdez R,Fenkart G,et al. Mechanisms of endogenous HIV-1 reactivation by endocervical epithelial cells[J]. J Virol,2020,94(9):e01904-e01919. [43] Shang L,Duan L,Perkey K E,et al. Epithelium-innate immune cell axis in mucosal responses to SIV[J]. Mucosal Immunol,2017,10(2):508-519. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.62 [44] Coelho A V C,Gratton R,Melo J P B,et al. HIV-1 infection transcriptomics: Meta-Analysis of CD4+ T cells gene expression profiles[J]. Viruses,2021,13(2):244. doi: 10.3390/v13020244 [45] Sun B,da Costa K A S,Alrubayyi A,et al. HIV/HBV coinfection remodels the immune landscape and natural killer cell ADCC functional responses[J]. Hepatology,2024,80(3):649-663. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000877 [46] Fisher B S,Green R R,Brown R R,et al. Liver macrophage-associated inflammation correlates with SIV burden and is substantially reduced following cART[J]. PLoS Pathog,2018,14(2):e1006871. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006871 [47] Roscic-Mrkic B,Fischer M,Leemann C,et al. RANTES (CCL5) uses the proteoglycan CD44 as an auxiliary receptor to mediate cellular activation signals and HIV-1 enhancement[J]. Blood,2003,102(4):1169-1177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0488 [48] Del Corno M,Liu Q H,Schols D,et al. HIV-1 gp120 and chemokine activation of Pyk2 and mitogen-activated protein kinases in primary macrophages mediated by calcium-dependent,pertussis toxin-insensitive chemokine receptor signaling[J]. Blood,2001,98(10):2909-2916. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.10.2909 [49] Zhang R Z,Kane M. Insights into the role of HIV-1 Vpu in modulation of NF-ĸB signaling pathways[J]. mBio,2023,14(4):e0092023. [50] Wang H,Liu Y,Huan C,et al. NF-κB-interacting long noncoding RNA regulates HIV-1 replication and latency by repressing NF-κB signaling[J]. J Virol,2020,94(17):e01057-20. [51] Chan J K,Greene W C. NF-κB/Rel: Agonist and antagonist roles in HIV-1 latency[J]. Curr Opin HIV AIDS,2011,6(1):12-18. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834124fd [52] O'Connell P,Pepelyayeva Y,Blake M K,et al. SLAMF7 is a critical negative regulator of IFN-α-mediated CXCL10 production in chronic HIV infection[J]. J Immunol,2019,202(1):228-238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800847 [53] Sturt A S,Webb E L,Patterson C,et al. Cervicovaginal immune activation in zambian women with female genital schistosomiasis[J]. Front Immunol,2021,12:620657. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.620657 [54] Chen J,He Y,Zhong H,et al. Transcriptome analysis of CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals receiving ART with LLV revealed novel transcription factors regulating HIV-1 promoter activity[J]. Virol Sin,2023,38(3):398-408. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2023.03.001 [55] Blondin-Ladrie L,Fourcade L,Modica A,et al. Monocyte gene and molecular expression profiles suggest distinct effector and regulatory functions in beninese HIV highly exposed seronegative female commercial sex workers[J]. Viruses,2022,14(2):361. doi: 10.3390/v14020361 [56] Vanpouille C,Wells A,Wilkin T,et al. Sex differences in cytokine profiles during suppressive antiretroviral therapy[J]. Aids,2022,36(9):1215-1222. [57] Ao Z,Wang L,Mendoza E J,et al. Incorporation of ebola glycoprotein into HIV particles facilitates dendritic cell and macrophage targeting and enhances HIV-specific immune responses[J]. PLoS One,2019,14(5):e0216949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216949 [58] Hunegnaw R,Helmold Hait S,Enyindah-Asonye G,et al. A mucosal adenovirus prime/systemic envelope boost vaccine regimen elicits responses in cervicovaginal and alveolar macrophages of rhesus macaques associated with delayed SIV acquisition and B cell help[J]. Front Immunol,2020,11:571804. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.571804 [59] Ka'e A C,Nanfack A J,Ambada G,et al. Inflammatory profile of vertically HIV-1 infected adolescents receiving ART in cameroon: A contribution toward optimal pediatric HIV control strategies[J]. Front Immunol,2023,14:1239877. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1239877 [60] Petkov S,Herrera C,Else L,et al. Mobilization of systemic CCL4 following HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in young men in Africa[J]. Front Immunol,2022,13:965214. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.965214 -

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: