Comparative Analysis of caIMR and CMR in Assessing Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Correlation of Cardiac and Cerebral Microvascular Lesions

-

摘要:

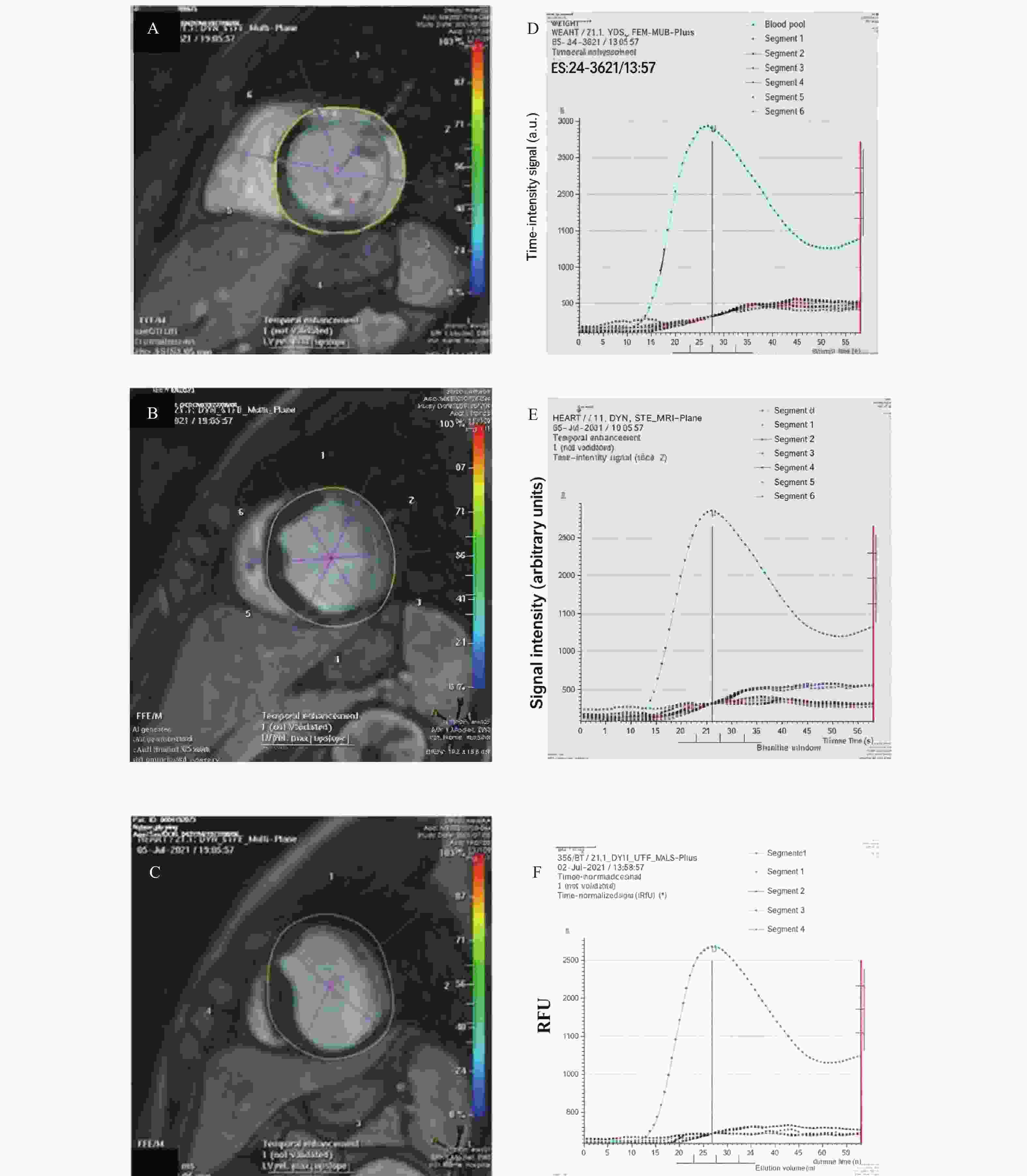

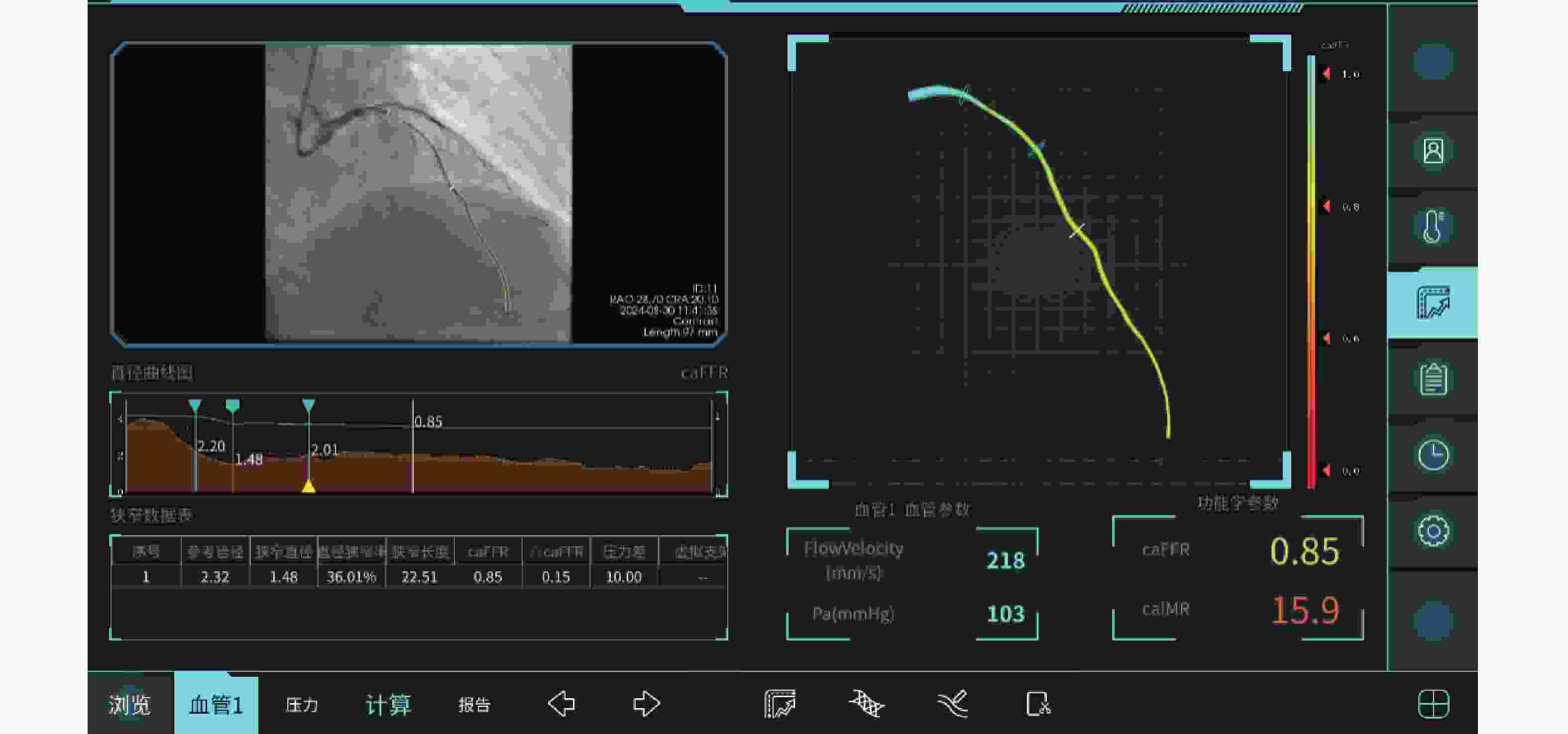

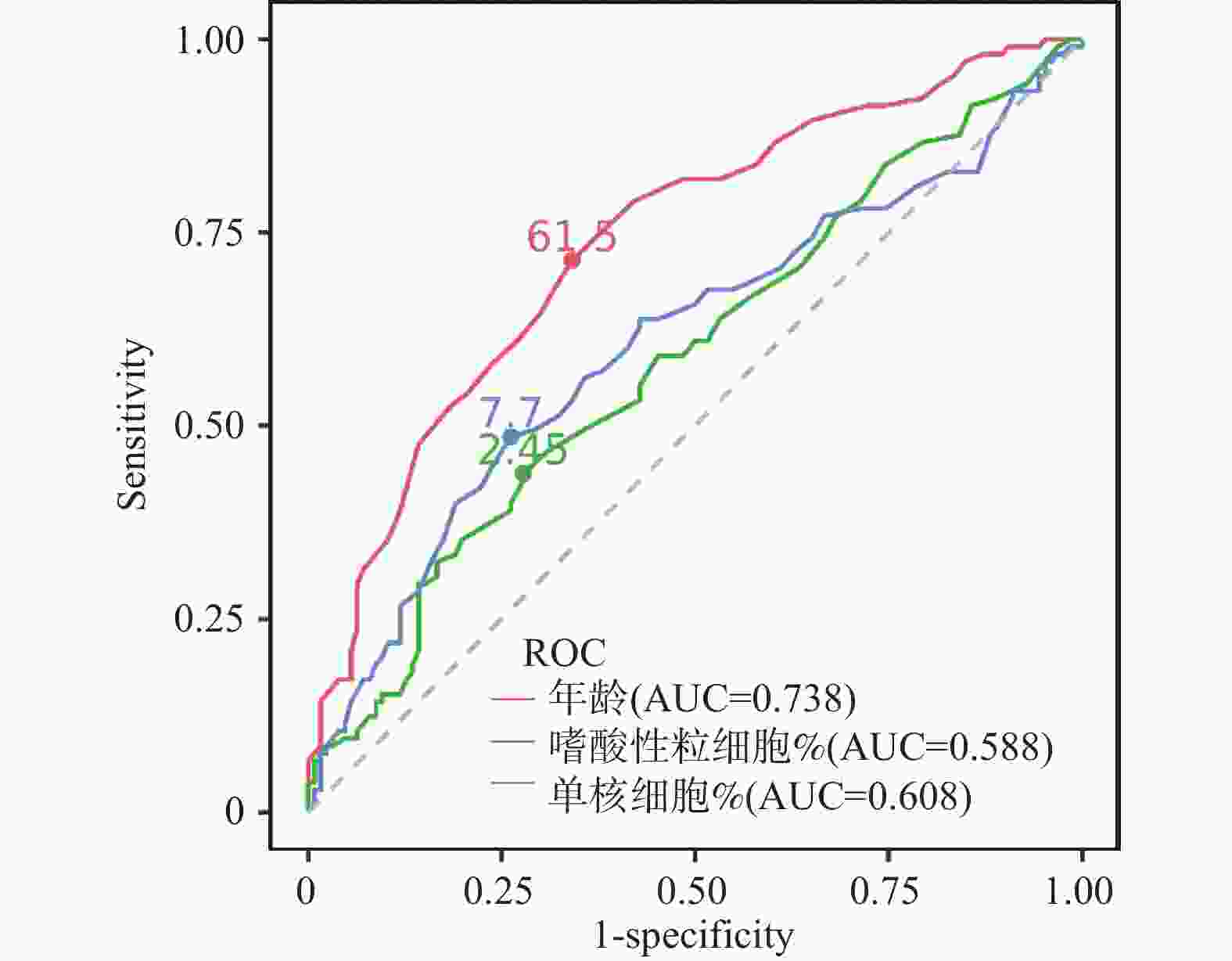

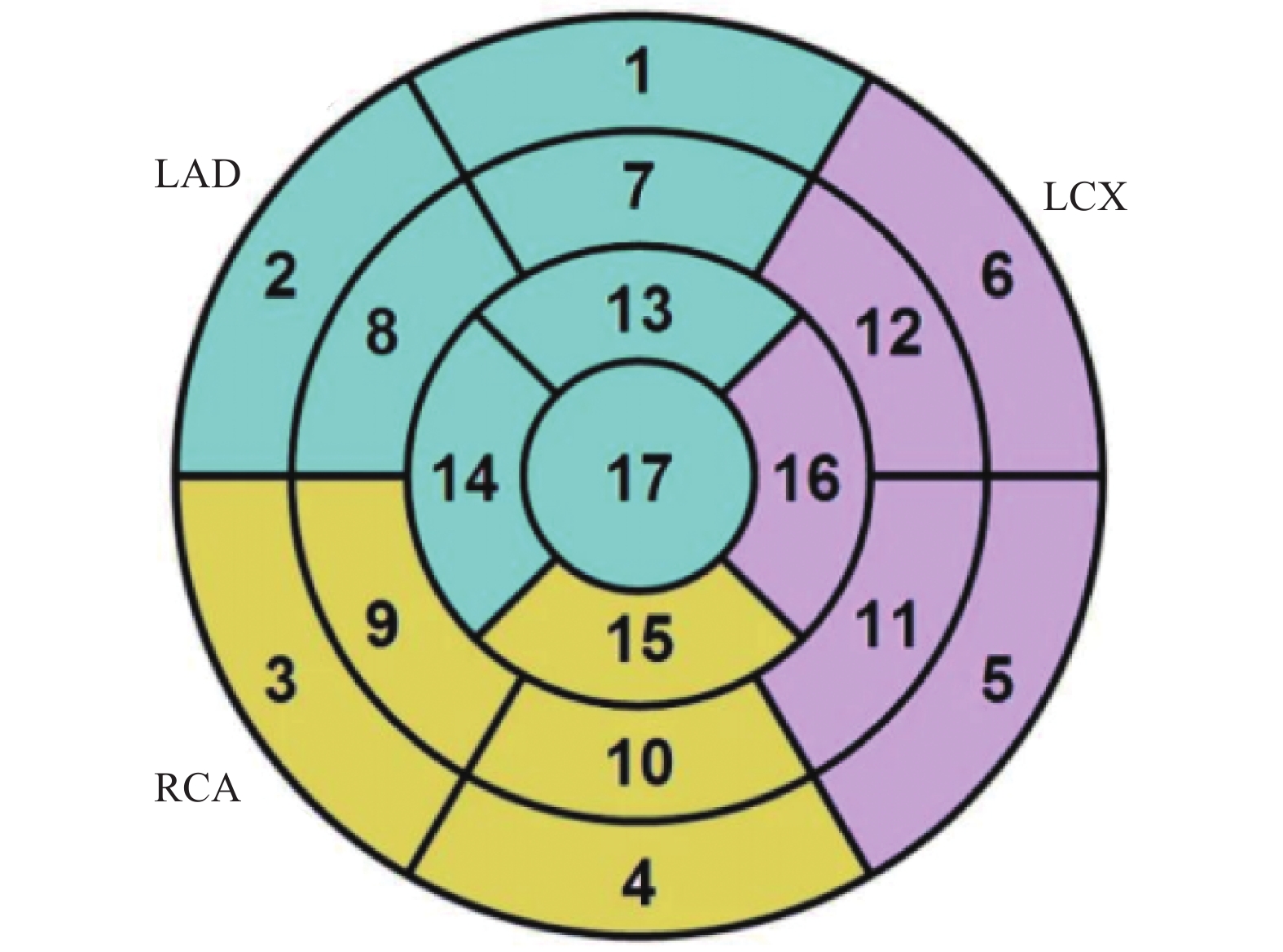

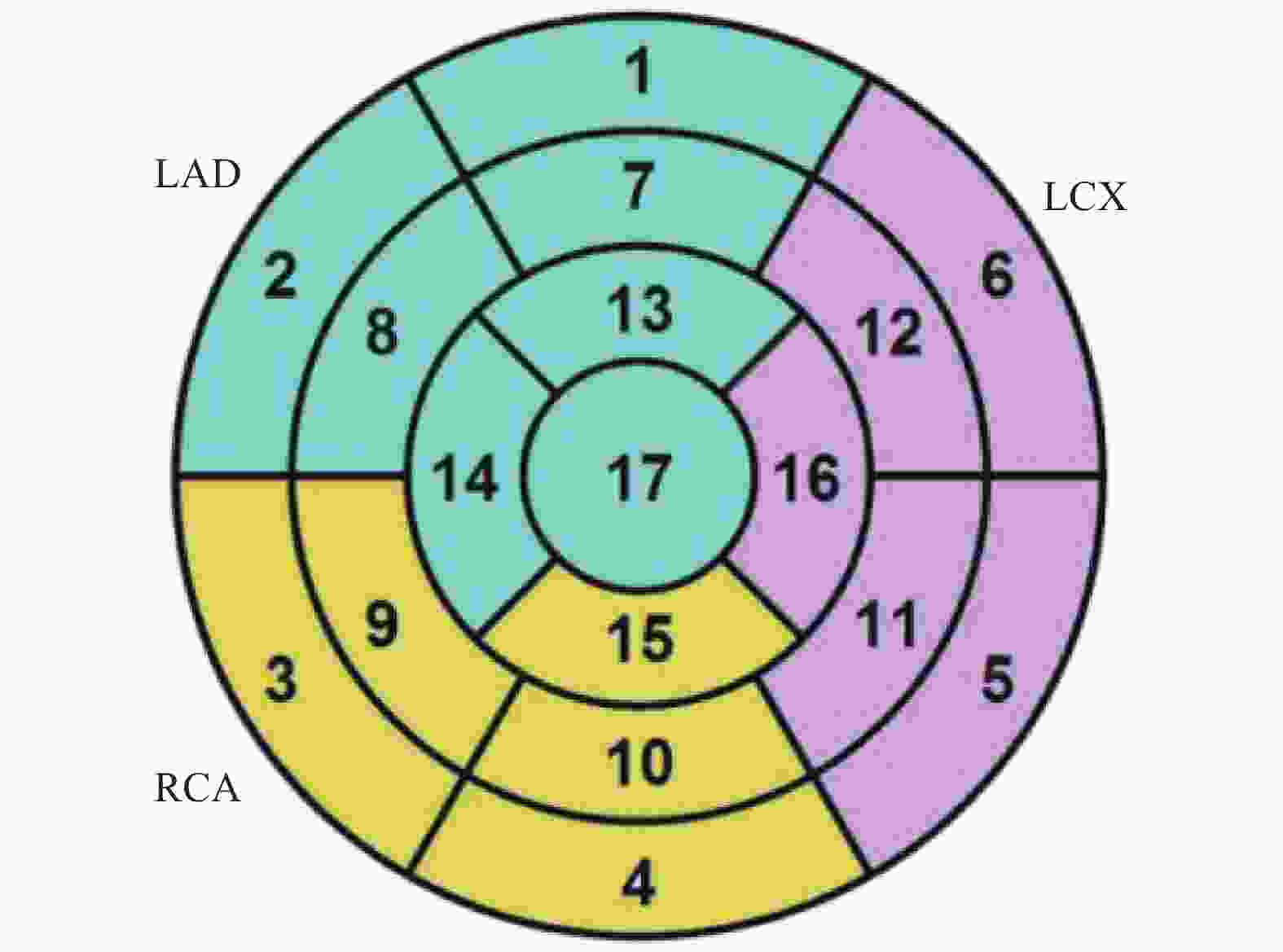

目的 通过心脏磁共振评估基于冠状动脉造影的微循环阻力指数对于冠状动脉微循环障碍的诊断效能,并进一步探究冠状动脉微循环障碍与无症状脑梗死间的相关性。 方法 选取2021年1月至2024年12月期间就诊于昆明医科大学第二附属医院心血管内科的患者231例。通过FlashAngio系统对冠状动脉造影图像左前降支血管进行分析得出caIMR值,以25为界限分为冠状动脉微循环正常组(caIMR<25,n = 126)和冠状动脉微循环障碍组(caIMR≥25,n = 105)。收集所有患者的一般临床资料、实验室指标(血常规、生化全套、糖化血红蛋白)、颅脑CT/MRI结果、心肌微循环磁共振灌注参数(达峰时间(tpeak)、相对峰值信号强度(RSIpeak)、最大上升斜率(Slopemax))、经胸超声心动图常规参数。 结果 (1)50例同时完善CMR和caIMR的患者, caIMR≥25组左前降支支配区域出现了不同程度的tpeak延长,RSIpeak和Slopemax降低,表明caIMR≥25组存在冠状动脉微循环障碍。进行Cohen's Kappa检验一致性分析, Kappa值0.839(P < 0.05),表明caIMR对于CMD的识别具有较高的准确度和评价效果;(2)127例糖尿病患者按照糖化血红蛋白(HbA1c)水平分为血糖控制良好组(4%≤HbA1c<6%)、血糖控制不佳组(6%≤HbA1c<8%)、血糖控制差组(HbA1c≥8%)。40例血糖控制良好组、59例血糖控制不佳组及28例血糖控制差组患者对比,血糖控制不佳组和血糖控制差组caIMR值中位数均高于血糖控制良好组(P < 0.05),且血糖控制不佳组caIMR中位数24.60接近于诊断冠状动脉微循环障碍的caIMR分界值25,血糖控制差组caIMR中位数32.15远高于分界值25;(3)在冠状动脉微循环障碍组中发现很多患者同时存在无症状脑梗死,而在冠状动脉微循环正常组患者中则较少,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。进一步进行Phi系数相关性分析,Phi系数0.562,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.001)。提示冠状动脉微循环障碍与无症状脑梗死之间存在相关性。 结论 caIMR对于冠状动脉微循环功能障碍的识别具有较高准确度,且与心脏磁共振的评估效能一致性较高,而在冠状动脉微循环障碍的患者中发现大多同时存在无症状脑梗死,说明心脑微血管两者之间的病变发展可能存在相关性。 Abstract:Objective To evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of coronary angiography-based microcirculatory resistance index for coronary microcirculatory dysfunction through cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), and further explore the correlation between coronary microcirculatory dysfunction and silent cerebral infarction. Methods 231 patients from the Cardiovasology Department of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University between January 2021 and December 2024 were selected. The caIMR value of the left anterior descending coronary artery was analyzed using the FlashAngio system, with patients divided into normal coronary microcirculation group (caIMR<25, n = 126) and coronary microcirculatory dysfunction group (caIMR≥25, n = 105). General clinical data, laboratory indicators (complete blood count, biochemical panel, glycated hemoglobin), cranial CT/MRI results, cardiac microcirculatory perfusion MRI parameters (time to peak [tpeak], relative signal intensity at peak [RSIpeak], maximum upslope [Slopemax]), and routine transthoracic echocardiography parameters of all patients were collected. Results (1) Among 50 patients who completed both CMR and caIMR, the caIMR≥25 group showed varying degrees of tpeak prolongation, with reduced RSIpeak and Slopemax, indicating coronary microcirculatory dysfunction. Cohen's Kappa consistency analysis showed a Kappa value of 0.839 (P < 0.05), suggesting high accuracy of caIMR in identifying CMD; (2) 127 diabetic patients were categorized based on HbA1c levels into good glycemic control group (4%≤HbA1c<6%), moderate glycemic control group (6%≤HbA1c<8%), and poor glycemic control group (HbA1c≥8%). Comparing 40 patients in the good control group, 59 in the moderate control group, and 28 in the poor control group, the median caIMR values in the moderate and poor control groups were higher than the good control group (P < 0.05). The moderate control group's median caIMR of 24.60 was close to the diagnostic threshold of 25, while the poor control group's median caIMR of 32.15 was significantly higher; (3) In the coronary microcirculatory dysfunction group, several patients simultaneously had silent cerebral infarction, which was less common in the normal microcirculation group, with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Further Phi coefficient correlation analysis showed a coefficient of 0.562, with statistically significant difference (P < 0.001), suggesting a correlation between coronary microcirculatory dysfunction and silent cerebral infarction. Conclusion caIMR demonstrates high accuracy in identifying coronary microcirculatory dysfunction, with good consistency with CMR assessment. The high prevalence of silent cerebral infarction in patients with coronary microcirculatory dysfunction suggests potential interconnected pathological development in cerebral and cardiac microvascular systems. -

表 1 冠状动脉微循环正常组与冠状动脉微循环障碍组一般资料比较[($ \bar x \pm s $)/n(%)]

Table 1. Comparison of general data between the normal coronary microcirculation group and the coronary microcirculation dysfunction group[($ \bar x \pm s $)/n(%)]

项目 冠状动脉微

循环正常组

(n=126)冠状动脉微

循环障碍组

(n=105)χ2/U/t P 年龄(岁) 57.69 ± 10.77 67.06 ± 10.19 6.743 <0.001* BMI(Kg/m2) 24.75 ± 4.56 24.38 ± 3.34 7089.500 0.349 性别 0.004 0.835 男 88(69.8) 72(68.6) 女 38(30.2) 33(31.4) 高血压 3.859 0.034* 有 88(69.8) 86(81.9) 无 38(30.2) 19(18.1) 糖尿病 0.611 0.091 有 62(49.2) 65(61.9) 无 64(50.8) 40(38.1) 吸烟史 1.853 0.135 有 62(49.2) 62(59.0) 无 64(50.8) 43(41.0) 冠心病史 10.800 0.001* 有 46(36.5) 62(59.0) 无 80(63.5) 43(41.0) 降血脂药物服用 13.643 0.071 是 45 (35.7) 64 (61.0) 否 81 (64.3) 41 (39.0) *P < 0.05。 表 2 冠状动脉微循环正常组与冠状动脉微循环障碍组血液学指标比较[M(P25,P75)/($ \bar x \pm s $)]

Table 2. Comparison of hematological indicators between the normal coronary microcirculation group and the coronary microcirculation dysfunction group[M(P25,P75)/($ \bar x \pm s $)]

血液学指标 冠状动脉微循环

正常组(n=126)冠状动脉微循环

障碍组(n=105)U/t P UREA(mmol/L) 5.39 (4.44,6.66) 5.58 (4.58,7.00) 6405.500 0.679 UA(μmol/L) 395.46±116.73 380.87±100.02 6981.500 0.314 TCHOL(mmol/L) 4.39 (3.67,5.26) 3.87 (3.27,4.59) 8214.500 0.002* TG(mmol/L) 1.66 (1.19,2.43) 1.51 (1.03,2.19) 7484.000 0.086 HDL-C(mmol/L) 1.07 (0.92,1.25) 1 (0.88,1.23) 7289.500 0.183 LDL-C(mmol/L) 2.65 (2.15,3.22) 2.26 (1.71,2.94) 8145.500 0.002* NONHDL(mmol/L) 3.41±1.18 2.95±0.97 8110.500 0.002* APOA1(g/L) 1.22±0.22 1.18±0.23 7191.500 0.255 APOB(g/L) 1.02±0.32 0.91±0.29 7907.900 0.011* Lp(a)(g/L) 8.25 (5.52,21.37) 9.2 (6.00,18.90) 6152.500 0.361 GLU(mmol/L)

HCY(μmol/L)5.36 (4.88,6.77)

13.635(10.69,15.92)5.31 (4.78,6.41)

13.97 (11.50,17.77)6906.500

5895.0000.565

0.155MONO% 6.71±1.75 7.41±2.15 5187.000 0.005* EO% 2.17±1.89 2.98±2.83 5454.000 0.022* NEUT(*109/L) 4.46±1.66 4.21±1.98 1.706 0.043* EO(*109/L) 0.115 (0.05,0.17) 0.12 (0.07,0.24) 5867.500 0.139 RBC(*1012/L) 4.91±0.72 4.67±0.69 2.489 0.013* HGB(g/L) 149.58±22.38 142.96±21.53 2.279 0.030* HCT(L/L) 0.46 (0.42,0.49) 0.44 (0.40,0.48) 7633.000 0.044* MCHC(g/L) 329 (32.00,336.75) 327 (319.00,333.00) 2.101 0.037* *P < 0.05。 表 3 冠状动脉微循环正常组与冠状动脉微循环障碍组心脏超声结果比较[M(P25,P75)]

Table 3. Comparison of echocardiographic results between the normal coronary microcirculation group and the coronary microcirculation dysfunction group[M(P25,P75)]

心脏

超声冠状动脉微循环

正常组(n=126)冠状动脉微循环

障碍组(n=105)U P LVEF 63(53.50,67.00) 62(55.00,67.00) 6541.000 0.884 LVDd 48(44.00,52.00) 47(44.00,52.00) 6700.500 0.866 LAD 34(30.25,37.00) 35(32.00,38.00) 6054.500 0.267 RVDd

RAD23(21.00,24.00)

32(30.00,34.00)23(22.00,24.00)

32(30.00,35.00)5553.500

6310.0000.034*

0.545*P < 0.05。 表 4 冠状动脉微循环正常组与冠状动脉微循环障碍组颅脑CT/MRI结果比较[n(%)]

Table 4. Comparison of cranial CT/MRI results between the normal coronary microcirculation group and the coronary microcirculation dysfunction group[n(%)]

颅脑CT/MRI 冠状动脉微循环

正常组(n=126)冠状动脉微循环

障碍组(n=105)χ2 P SBI 70.817 <0.001* 是 23 (18.3) 78 (74.3) 否 103 (81.7) 27 (25.7) *P < 0.05。 表 5 冠状动脉微循环正常组与冠状动脉微循环障碍组冠状动脉生理指标比较[($ \bar x \pm s $)/M(P25,P75)]

Table 5. Comparison of coronary physiological indicators between the normal coronary microcirculation group and the coronary microcirculation dysfunction group[($ \bar x \pm s $)/M(P25,P75)

项目 冠状动脉微循环正常组(n=126) 冠状动脉微循环障碍组(n=105) U P 冠状动脉参考管腔 2.47±0.57 2.43±0.51 6854.500 0.530 冠状动脉狭窄直径 1.61±0.45 1.59±0.41 6488.500 0.930 冠状动脉直径狭窄率 0.34(0.23,0.43) 0.32(0.25,0.42) 6762.000 0.772 冠状动脉狭窄长度 14.15(9.08,19.49) 12.33(8.41,16.87) 7279.500 0.189 冠状动脉内压力差 4(2.00,11.75) 3(2.00,7.00) 7688.000 0.133 表 6 冠状动脉微循环障碍的多因素Logistic回归分析

Table 6. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis of coronary microcirculation dysfunction

因素 B SE Waldχ2 P OR 95%CI SBI 2.957 0.439 45.393 <0.001* 19.241 8.140~45.480 年龄 0.048 0.022 5.053 0.025* 1.952 1.912~3.993 高血压史

冠心病史−0.108

−0.0020.472

0.8370.052

0.0000.818

0.9970.897

0.9970.355~2.262

0.193~5.149TCHOL −0.621 0.835 0.553 0.457 0.537 0.105~2.760 LDL-C 0.304 0.865 0.123 0.726 1.354 0.248~7.387 NONHDL 1.132 0.973 1.354 0.245 3.103 0.461~20.907 APOB 0.004 1.821 0.000 0.997 1.004 0.028~35.621 MONO% 0.222 0.097 5.251 0.022* 1.800 1.661~1.968 EO% 0.170 0.085 4.046 0.044* 1.843 1.714~1.995 RBC 0.601 0.742 0.655 0.418 1.824 0.426~7.816 HGB −0.024 0.070 0.121 0.728 0.976 0.851~1.119 HCT 0.041 21.349 0.000 0.998 1.043 0.000~1.551 MCHC 0.042 0.039 1.152 0.283 1.043 0.966~1.125 *P < 0.05。 表 7 CMD与SBI的Phi系数分析

Table 7. Phi coefficient analysis of CMD and SBI

项目 SBI 非SBI 总计 CMD 78 27 105 非CMD 23 103 126 总计 101 130 231 Phi系数:0.562(P < 0.001);Phi系数>0.5表示具有较强相关性;P < 0.05。 表 8 预测CMD发生的诊断价值

Table 8. Diagnostic value for predicting the occurrence of CMD

危险因素 曲线下面积 灵敏度 特异度 约登指数 95%CI P 年龄 0.738 0.714 0.659 0.373 0.674~0.803 <0.001* MONO% 0.608 0.486 0.738 0.160 0.533~0.683 0.005* EO% 0.588 0.438 0.722 0.224 0.514~0.662 0.020* *P < 0.05。 表 9 caIMR<25组与caIMR≥25组tpeak比较[M(P25,P75)]

Table 9. Comparison of tpeak between the caIMR < 25 group and the caIMR ≥ 25 group[M(P25,P75)]

节段 caIMR<25组(n=24) caIMR≥25组(n=26) U/t P 1 20.50 (13.40,22.57) 36.35 (26.55,48.92) 124.000 <0.001* 2 15.30 (11.70,20.25) 31.00 (23.37,42.62) 81.500 <0.001* 7 21.65 (14.40,25.30) 34.95 (26.87,39.55) 4.438 <0.001* 8 22.00 (14.20,23.80) 35.05 (26.77,42.07) 103.500 <0.001* 13 19.50 (12.20,27.70) 29.90 (25.47,38.45) 155.000 0.001* 14 20.75 (12.50,29.55) 34.20 (25.02,42.17) 3.955 <0.001* *P < 0.05。 表 10 caIMR<25组与caIMR≥25组RSIpeak比较[M(P25,P75)]

Table 10. Comparison of RSIpeak between the caIMR < 25 group and the caIMR ≥ 25 group[M(P25,P75)]

节段 caIMR<25组(n=24) caIMR≥25组(n=26) U P 1 163.250 (106.525, 1099.375 )110.900 (90.225,136.425) 243.000 <0.001* 2 160.800 (123.600,232.725) 144.300 (106.750,997.725) 342.000 0.004* 7 182.700 (125.825, 1188.825 )125.550 (117.900,164.150) 259.500 <0.001* 8 142.000 (137.000,166.000) 159.600 (119.825, 1173.275 )287.000 0.253 13 207.250 (148.675, 1274.100 )189.700 (173.050,251.600) 310.000 0.001* 14 193.250 (164.475,221.300) 204.800 (149.125, 1187.375 )304.000 0.641 *P < 0.05。 表 11 caIMR<25组与caIMR≥25组Slopemax比较[M(P25,P75)]

Table 11. Comparison of slopemax between the caIMR < 25 group and the caIMR ≥ 25 group [M(P25,P75)]

节段 caIMR<25组(n=24) caIMR≥25组(n=26) U P 1 12.500 (8.000,68.775) 10.100 (6.700,12.100) 284.500 <0.001* 2 16.950 (9.800,30.275) 13.950 (8.650,63.550) 340.500 <0.001* 7 12.200 (9.825,14.750) 12.400 (8.650,64.350) 315.500 0.326 8 14.700 (11.325,16.100) 12.500 (8.775,59.350) 323.000 <0.001* 13 18.500 (13.975,36.400) 15.450 (10.850,91.625) 346.500 0.003* 14 17.900 (11.050,22.700) 16.900 (11.075,68.200) 316.500 0.001* *P < 0.05。 表 12 caIMR组与CMR组交叉表分析

Table 12. Cross-Tabulation analysis between the caIMR group and the CMR group

CMR组 总计 CMD 非CMD caIMR组 CMD 24 2 26 非CMD 2 22 24 总计 26 24 50 表 13 caIMR组与CMR组Cohen's Kappa检验

Table 13. Cohen's Kappa test between the caIMR group and the CMR group

项目 Kappa z P 标准误 95%CI caIMR、CMR 0.840 5.938 <0.001* 0.154 0.688~0.990 *P < 0.05;Kappa值0.81 ~ 1.00表示一致性好。 表 14 三组间caIMR值比较[M(P25,P75)]

Table 14. Comparison of caIMR values among three groups[M(P25,P75)]

项目 NGSP-HbA1c F P 血糖控制良好组(n=40) 血糖控制不佳组(n=59) 血糖控制差组(n=28) caIMR 22.25(18.12,27.70) 24.60(20.05,33.35) 32.15(24.17,38.47) 4.560 0.014* *P < 0.05。 表 15 三组间无症状脑梗死患者比较[n(%)]

Table 15. Comparison of patients with silent brain infarction among three groups[n(%)]

项目 NGSP-HbA1c χ2 P 血糖控制

良好组(n=40)血糖控制

不佳组(n=59)血糖控制

差组(n=28)无症状

脑梗死6.456 0.029* 有 17 (42.5) 32 (54.2) 21 (75.0) 无 23 (57.5) 27 (45.8) 7 (25.0) *P < 0.05。 -

[1] Roth G A, Mensah G A, Johnson C O, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2020, 76(25): 2982-3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 [2] Martin S S, Aday A W, Allen N B, et al. 2025 heart disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the american heart association[J]. Circulation, 2025, 151(8): e41-e660. [3] Ong P, Camici P G, Beltrame J F, et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina[J]. International Journal of Cardiology, 2018, 250: 16-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.068 [4] Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes[J]. European Heart Journal, 2020, 41(3): 407-477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425 [5] Gdowski M A, Murthy V L, Doering M, et al. Association of isolated coronary microvascular dysfunction with mortality and major adverse cardiac events: A systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data[J]. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2020, 9(9): e014954. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014954 [6] Taqueti V R, Di Carli M F. Coronary microvascular disease pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic options: JACC state-of-the-art review[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2018, 72(21): 2625-2641. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.042 [7] Benenati S, Campo G, Seitun S, et al. Ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery (INOCA): non-invasive versus invasive techniques for diagnosis and the role of #FullPhysiology[J]. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 2024, 127: 15-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2024.07.017 [8] Xu X, Divakaran S, Weber B N, et al. Relationship of subendocardial perfusion to myocardial injury, cardiac structure, and clinical outcomes among patients with hypertension[J]. Circulation, 2024, 150(14): 1075-1086. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.067083 [9] Jespersen L, Hvelplund A, Abildstrøm S Z, et al. Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events[J]. European Heart Journal, 2012, 33(6): 734-744. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr331 [10] Bochaton T, Lassus J, Paccalet A, et al. Association of myocardial hemorrhage and persistent microvascular obstruction with circulating inflammatory biomarkers in STEMI patients[J]. PLOS One, 2021, 16(1): e0245684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245684 [11] Ai H, Feng Y, Gong Y, et al. Coronary angiography-derived index of microvascular resistance[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2020, 11: 605356. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.605356 [12] 姜波, 陈玉成, 贺勇. 心脏磁共振成像技术在急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊治中的应用价值[J]. 心血管病学进展, 2016, 37(2): 103-107. [13] 李璐, 赵世华. 磁共振成像识别急性心肌梗死后微循环障碍的研究进展[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2019, 47: 335-338. [14] Feng C, Abdu F A, Mohammed A Q, et al. Prognostic impact of coronary microvascular dysfunction assessed by caIMR in overweight with chronic coronary syndrome patients[J]. Frontiers in endocrinology, 2022, 13: 922264. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.922264 [15] 中华医学会心血管病学分会介入心脏病学组, 中华医学会心血管病学分会动脉粥样硬化与冠心病学组, 中国医师协会心血管内科医师分会血栓防治专业委员会, 等. 稳定性冠心病诊断与治疗指南[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2018, 46(9): 680-694. [16] Eran A, Erdmann E, Er F. Informed consent prior to coronary angiography in a real world scenario: What do patients remember?[J]. PLOS One, 2010, 5(12): e15164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015164 [17] 中华医学会神经病学分会, 中华医学会神经病学分会脑血管病学组. 中国无症状脑梗死诊治共识[J]. 中华神经科杂志, 2018, 51(9): 692-698. [18] Huang D, Gong Y, Fan Y, et al. Coronary angiography-derived index for assessing microcirculatory resistance in patients with non-obstructed vessels: The FLASH IMR study[J]. American Heart Journal, 2023, 263: 56-63. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2023.03.016 [19] Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10204): 1145-1158. [20] 王亚楠, 吴思缈, 刘鸣. 中国脑卒中15年变化趋势和特点[J]. 华西医学, 2021, 36(6): 803-807. [21] Gupta A, Giambrone A E, Gialdini G, et al. Silent brain infarction and risk of future stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Stroke, 2016, 47(3): 719-725. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011889 [22] Lim J S, Kwon H M. Risk of “silent stroke” in patients older than 60 years: Risk assessment and clinical perspectives[J]. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2010, 5: 239-251. [23] Maaijwee N A M M, Rutten-Jacobs L C A, Arntz R M, et al. Long-term increased risk of unemployment after young stroke: A long-term follow-up study[J]. Neurology, 2014, 83(13): 1132-1138. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000817 [24] Leary M C, Saver J L. Annual incidence of first silent stroke in the United States: A preliminary estimate[J]. Cerebrovascular Diseases (basel, Switzerland), 2003, 16(3): 280-285. doi: 10.1159/000071128 [25] Cho E R, Kim H, Seo H S, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for silent cerebral infarction[J]. Journal of Sleep Research, 2013, 22(4): 452-458. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12034 [26] Oh S H, Kim N K, Kim S H, et al. The prevalence and risk factor analysis of silent brain infarction in patients with first-ever ischemic stroke[J]. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 2010, 293(1-2): 97-101. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.02.025 [27] Fanning J P, Wong A A, Fraser J F. The epidemiology of silent brain infarction: A systematic review of population-based cohorts[J]. BMC Medicine, 2014, 12: 119. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0119-0 [28] Zhao B, Li T, Fan Z, et al. Heart-brain connections: Phenotypic and genetic insights from magnetic resonance images[J]. Science, 2023, 380(6648): abn6598. doi: 10.1126/science.abn6598 [29] Rivard L, Friberg L, Conen D, et al. Atrial fibrillation and dementia: A report from the AF-SCREEN international collaboration[J]. Circulation, 2022, 145(5): 392-409. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055018 [30] Dridi H, Liu Y, Reiken S, et al. Heart failure-induced cognitive dysfunction is mediated by intracellular Ca2+ leak through ryanodine receptor type 2[J]. Nature Neuroscience, 2023, 26(8): 1365-1378. doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01377-6 [31] Kwapong Y A, Boakye E, Khan S S, et al. Association of depression and poor mental health with cardiovascular disease and suboptimal cardiovascular health among young adults in the United States[J]. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2023, 12(3): e028332. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.028332 [32] Mejia-Renteria H, Travieso A, Matías-Guiu J A, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is associated with impaired cognitive function: The cerebral-coronary connection study (C3 study)[J]. European Heart Journal, 2023, 44(2): 113-125. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac521 [33] Zhang H, Yang K, Chen F, et al. Role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis in cardiovascular disease: Pathogenesis and clinical implications[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022, 13: 975367. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975367 [34] Barkaway A, Rolas L, Joulia R, et al. Age-related changes in the local milieu of inflamed tissues cause aberrant neutrophil trafficking and subsequent remote organ damage[J]. Immunity, 2021, 54(7): 1494-1510. e7. [35] Nikolich-Žugich J. The twilight of immunity: Emerging concepts in aging of the immune system[J]. Nature Immunology, 2018, 19(1): 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0006-x [36] Rowe G, Tracy E, Beare J E, et al. Cell therapy rescues aging-induced beta-1 adrenergic receptor and GRK2 dysfunction in the coronary microcirculation[J]. Geroscience, 2022, 44(1): 329-348. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00455-6 [37] Manini T M, Anton S D, Beavers D P, et al. ENabling reduction of low-grade inflammation in SEniors pilot study: Concept, rationale, and design[J]. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2017, 65(9): 1961-1968. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14965 [38] Broch K, Anstensrud A K, Woxholt S, et al. Randomized trial of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2021, 77(15): 1845-1855. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.049 [39] Sagris M, Theofilis P, Antonopoulos A S, et al. Inflammation in coronary microvascular dysfunction[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(24): 13471. doi: 10.3390/ijms222413471 [40] Suhrs H E, Schroder J, Bové K B, et al. Inflammation, non-endothelial dependent coronary microvascular function and diastolic function-are they linked?[J]. PLOS One, 2020, 15(7): e0236035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236035 [41] Yu L. Meta-analysis of the correlation between inflammatory response indices and no-reflow after PCI in patients with acute STEMI[J]. American Journal of Translational Research, 2024, 16(10): 5168-5181. doi: 10.62347/SUQT4991 [42] Schroder J, Mygind N D, Frestad D, et al. Pro-inflammatory biomarkers in women with non-obstructive angina pectoris and coronary microvascular dysfunction[J]. International Journal of Cardiology. Heart & Vasculature, 2019, 24: 100370. [43] Andonian B J, Hippensteel J A, Abuabara K, et al. Inflammation and aging-related disease: A transdisciplinary inflammaging framework[J]. Geroscience, 2025, 47(1): 515-542. [44] Wasserman D H, Wang T J, Brown N J. The vasculature in prediabetes[J]. Circulation Research, 2018, 122(8): 1135-1150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311912 [45] Reindl M, Reinstadler S J, Feistritzer H, et al. Relation of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol with microvascular injury and clinical outcome in revascularized ST‐elevation myocardial infarction[J]. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2017, 6(10): e006957. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006957 [46] Bouchi R, Babazono T, Yoshida N, et al. Silent cerebral infarction is associated with the development and progression of nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Hypertension Research: Official Journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension, 2010, 33(10): 1000-1003. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.122 -

下载:

下载: